Labor & Economy

Building a Better Life: Bottom Lines and Top Priorities

My cousin and I have stayed in touch over the years despite the distance — he grew up in a Texas border town and has lived his adult life in Phoenix. Both he and his wife have held well-paid positions in the health field. Like most families, when we visit, we avoid subjects in-laws shouldn’t talk about, including politics and religion. But this time, he brought up the topic of unions, so over the next several days we talked intermittently about unions and why low wage workers need them.

On our final evening together, we sat across from each other in one of those expensive Santa Monica restaurants named after its chef. I said, “So here is the bottom line for me: People who work all day should be able to provide shelter and food for their families, and they ought to have health care.”

“I don’t know that I disagree with that,” he replied.

Then the conversation turned, and I decided to leave things on a word of agreement. But it made me think. If we agree on a bottom line of shelter, food and health care for full-time work, then the rest of the discussion should focus on ways to make it happen. Three obvious ones are:

- Raise the minimum wage. This is what a million employees in Los Angeles County earn but it doesn’t come close to what families need. In Australia the lowest wage workers earn $16 an hour, more than twice the U.S. rate. Their high level takes credit for Down Under skipping the Great Recession, even though its economy is tightly tied to the world financial system. Australian workers, even those only making minimum wage, apparently had the incomes to keep buying what they needed, while American workers slipped further behind.

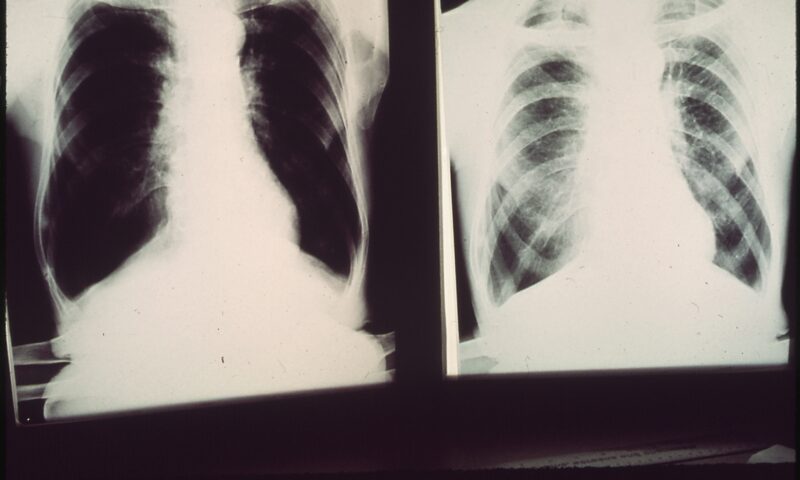

- Enact a single-payer universal health care program. Advocates know that one-third of health care dollars spent in this country go for non-medical costs such as overhead, management and profits. It is the main reason that this country spends more per person for health care than any other country in the world.

- Make forming a union easier. We could model a policy on the Canadian “card check” method. In their system, if a majority of employees sign a card saying they want a union, the company and the workers must sit down and work out an agreement within the year. No long, drawn out election process where the rules are stacked in favor of the employer and it takes years to redress grievances.

These three approaches, however, share one common problem: They require Congress to pass legislation. But the current Congress – along with the politics dominating a majority of states – won’t let that happen. Just whispering the words “minimum wage” generates a buzz-saw of opposition, and we all witnessed what happened to the best notions about national health care. Making it easier to organize workers? Not a chance.

So a number of unions are experimenting with new strategies that could give workers some of the benefits of a union:

- Worker Associations are not unions, but they look promising for employees working for anti-union, low-wage-paying companies like Walmart. Such associations don’t have the power to negotiate wages and work rules, but they do provide mutual support over grievances, solidarity in objecting to a manager’s arbitrariness and protection from sexual harassment, among other work-place matters.

- Work Actions have allowed employees in the fast food industry to mobilize across corporate lines and brand names to protest low wages and unfair working conditions. Just a few weeks ago thousands of low-wage workers in New York City left their jobs and went into the streets calling attention to their situation nationwide.

- Worker/Community Coalitions intentionally involve interest and neighborhood groups outside the work place itself. In last fall’s effort to pass the Long Beach ballot initiative that raised the minimum wage for 1900 hotel workers, the campaign included people from religious networks as well as neighborhood-serving small businesses. By engaging social sectors beyond workers, coalitions end the isolation of employees and bring bad corporate behavior to a broader public awareness.

No one knows whether any of these initiatives will succeed long-term in helping low-wage workers meet a decent bottom line, and they require a huge investment in time and resources on the part of unions, but they represent a growing number of successes. Of course, I don’t know what my cousin thinks about any of these approaches either, but I intend to find out the next time we get together.

-

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025A Coal Miner’s Daughter Takes on DOGE to Protect Miners’ Health

-

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025Detained Man Says ICE Isn’t Treating His Colon Cancer

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025Budget Cuts Threaten In-Home Assistance Workers and Medi-Cal Recipients

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025‘Patients Will Suffer. Patients Will Die.’ Why California’s Rural Hospitals Are Flatlining.

-

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025Can Gov. Gavin Newsom Make Californians Healthier?

-

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025Police Violently Crack Down on L.A. Protests

-

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025Grace Under Fire: Transgender Student Athlete AB Hernandez’s Winning Weekend

-

Striking BackJune 3, 2025

Striking BackJune 3, 2025In Georgia, Trump Is Upending Successful Pro-Worker Reforms