Reports that the new leader of the Catholic Church has mixed African ancestry offer a fascinating antidote to

President Trump’s attacks on diversity in America.

By Erin Aubry Kaplan

There is a wonderful and welcome irony to the fact that the Trump administration is working to sideline or silence the history of racial struggle in the United States while the new American pope is raising the profile of that struggle in a very unexpected way.

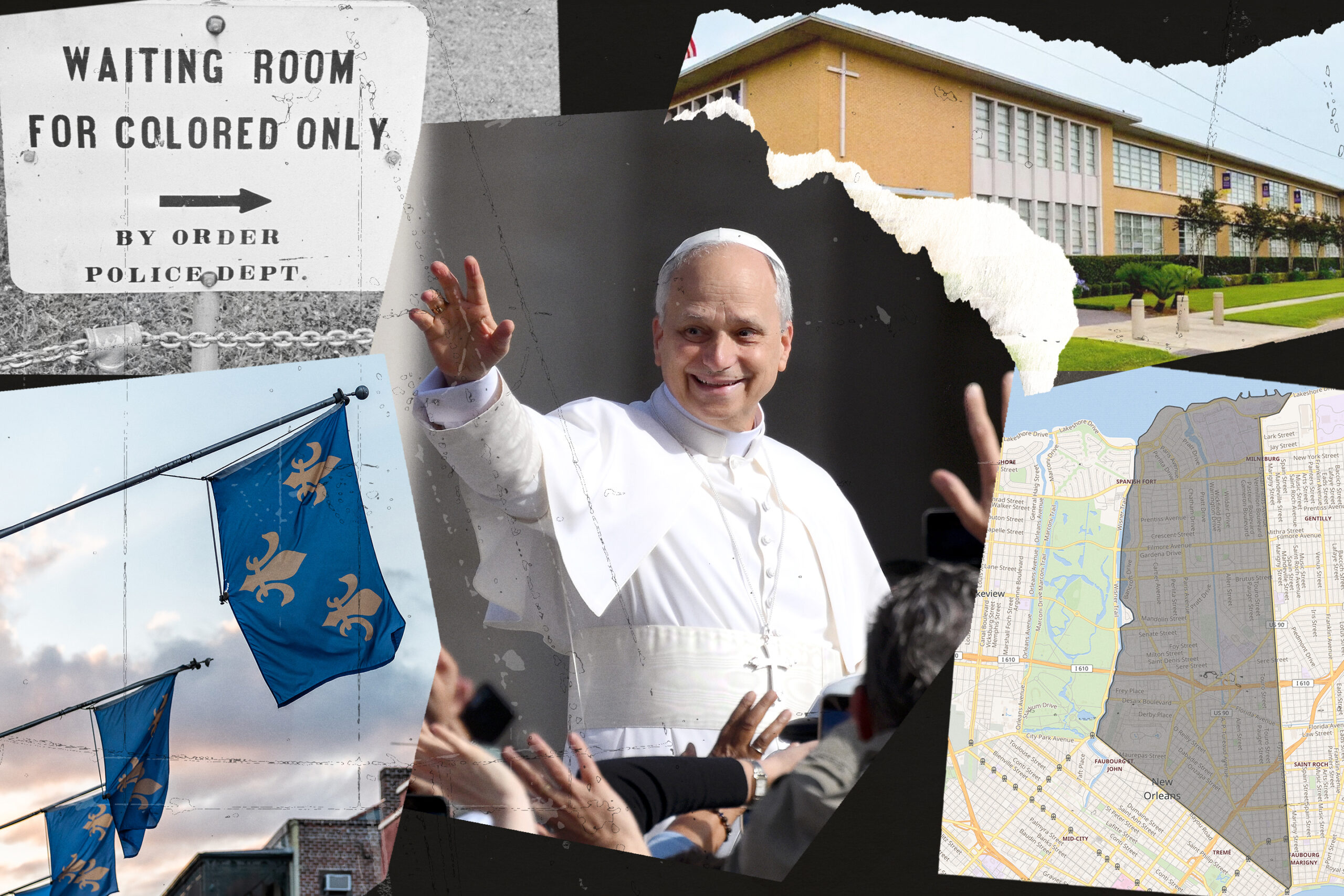

It’s remarkable enough that Pope Leo XIV, formerly known as Robert Francis Prevost, is the first pope from the United States, and the second to spend much of his career in Latin America. But the real revelation is that this man from Chicago has roots in Creole Louisiana, specifically the 7th Ward neighborhood of New Orleans.

“Creole,” which originally referred to French and Spanish-descended people who lived in the territory before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, has long referred to an ethnic and racial gumbo of people with Black, French, Spanish and Native American heritage.

It’s a unique subset of Black America, one that brings together a complicated and unresolved history of slavery, miscegenation and white fear of “race mixing” that gave rise to the local and state laws known as Jim Crow that enforced segregation after the Civil War, especially in the South.

This is Pope Leo’s history, courtesy of his maternal grandparents and great-grandparents who lived in the 7th Ward and who were quickly identified by a New Orleans genealogist as Afro Creole. The pope’s father has been described only as French and Italian, but it’s noteworthy that Prevost is a name familiar in the 7th Ward. Also noteworthy is that the pope’s brother, John Prevost, confirmed that the family has Black roots, but said he does not identify as Black.

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

All of this would be merely interesting were it not for the fact that being Black, including Creole, is never just a fact, it is a political stance. That was certainly the case for Creole people, despite an assumption among some observers that being lighter-skinned exempts them from racism or puts them above the fray. To the contrary, it puts them squarely at the center of it.

I was born in Los Angeles but my family is Creole, from the 7th Ward. Stories about “the oId country” I heard growing up included stories about the almost panicked efforts of white people to police the color line in New Orleans, to cleanly separate the races. I heard as many stories about some Creoles transgressing the line by “passing” — letting themselves be perceived as white in order to hold a job or get fair treatment — and living in terror of being found out.

Pope Leo has been outed, so to speak, to the great astonishment and satisfaction of Black people and particularly of Creoles. When I told my mother about his lineage, she was amazed, and then stoked — there is no other word for it. She’s stoked not just because a Creole from the provincial 7th Ward has ascended to the world stage. He’s also the pope of an ancient, all-powerful church that was part of the racial elite that made life in the American South so suffocating for people of color. Yet in their insulated neighborhoods Creoles made the Catholic Church into a community institution that was as culturally Creole as red beans, jambalaya and Mardi Gras. It was markedly different from the mainstream church, one of many ways Black people made the most out of segregation.

This church migrated west along with the waves of Creoles who left New Orleans for Los Angeles in the 1940s and ’50s — my family among them. Los Angeles was the last big city that promised more opportunity and, as important, less obsession with the color line.

Like so many immigrants in their new home, they re-created aspects of the old one. Creole traditions flourished, mostly in Crenshaw and South Central, in churches like Transfiguration, St. John of God, Holy Name, St. Anselm. These houses of worship were an intimate part of other Louisiana Creole traditions that included annual Mardi Gras celebrations, the Louisiana to Los Angeles (LALA) Festival, the social organization Autocrats West, feasts of St. Joseph and Friday night fish fries.

Over the ensuing decades, the Creole population of Los Angeles has ebbed sharply, and Catholic churches have become more Latino and centered on immigrants from outside the country, not the American South. But New Orleans has left an indelible mark on L.A., religiously and politically.

My uncle Leon Aubry was a barber and entrepreneur who was also an activist involved in Catholics United for Racial Equality in the 1960s, amongst other local justice campaigns. His younger brother Larry, my father, was also an activist who was emphatically not a practicing Catholic; the way the faith was segregated in New Orleans offended him, he told me. But he respected the traditions of family, of all the things that shored up Black people’s identity and dignity and held it together through hard times. The church was one of them.

Pope Leo’s ascension is not a salve for all the wounds the church has inflicted on Black people, but it is a kind of divine affirmation.

When my parents were growing up there were no Black priests or officiants. The Catholic schools virtually everybody attended didn’t even have Black or Creole teachers or administrators. White priests and nuns, who were frequently of Irish or some other European descent, were not always sensitive, to say the least — and could be clueless about the racial subtleties of the 7th Ward. My mother recalled a newly arrived white nun demanding to know “Where are all the colored kids?” The invisibility that all Black people fought against had specific meaning for Creoles, whose physical appearance obscured traditional color lines and often confused whites who thought they knew what Blackness looked like. At the same time, that appearance called the very premise of color and race into question.

That Leo himself doesn’t publicly speak about his Creole heritage (at least not yet) is a kind of “passing in plain sight” that many Creoles know very well. But his silence thus far doesn’t really matter: They know who he is and where he comes from.

It hardly seems a coincidence now that the man recently chosen as pope has spoken out in the past against racial injustice, and that he was a missionary in the Order of Saint Augustine, the saint for whom a prominent 7th Ward Catholic boy’s school is named.

I’m sure none of this sits well with Donald Trump — if he’s even absorbed it — given his push to reassert the full power of a white American state — a fight that’s become almost religious in its fervor and its refusal to compromise with Americans and other residents who aren’t powerful or unambiguously white.

The president will be sharing the global spotlight and influence with a pope who personally knows all about the hypocrisies, lies and fear that built America’s racial hysteria, which has been checked at points but never extinguished, and is now threatening to consume us all.

Creole people have brightly illuminated the existential threat to democracy posed by that hysteria throughout America’s history, and fought against it. Hopefully Pope Leo will provide more illumination at another very critical moment.

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main