Coronavirus

Selling the Vaccine Becomes Tougher in Certain Communities

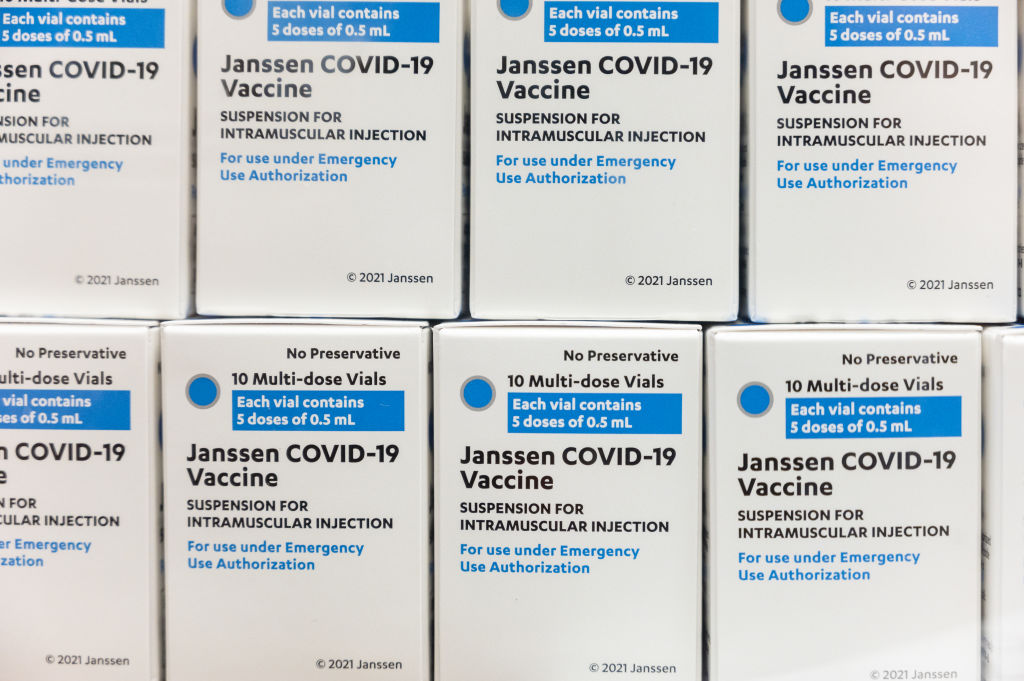

The Johnson & Johnson pause threatens to exacerbate vaccination hesitancy.

In the hours after two federal agencies recommended a pause on Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccinations, a question quickly emerged: Will the setback promote new skepticism among those who were leery of taking a vaccine dose in the first place?

Co-published by Patch

At a White House briefing early Tuesday, Jeff Zients, who is leading President Biden’s coronavirus response team, was asked that question. His response: “I think you need to be transparent about what the science is telling us. Today’s action is clear evidence that they’re taking every step necessary to ensure the American people have clear and transparent information about the safety and effectiveness of these vaccines.”

Zients was accompanied by Dr. Anthony Fauci, Biden’s chief medical adviser. Fauci used his time to reinforce the idea that Biden’s administration is being guided by science, meaning that the Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration are the ones making the calls. The pause, due to a rare but dangerous clotting issue, is “a testimony to how seriously we take safety and why we have an FDA and a CDC that looks at this very carefully,” he said.

Neither of the officials’ responses answered the original question – but those with boots on the ground can do that. Among them, there is no disagreement: The J&J pause is going to make vaccination a tougher sell, especially in communities of color where distrust of the process was already significant. The real question is how to minimize that damage and get back to the work of making the country safer from a deadly virus.

“The unfortunate events surrounding the J&J vaccine will exacerbate an already troublesome vaccine rollout,” Michelle Burton, chief strategy officer for the Social Change Institute in Los Angeles, told Capital & Main on Tuesday.

“Ultimately, honesty will be the best policy,” said Michelle Burton of the Social Change Institute. “Leveraging the support of trusted voices on the ground in communities of color is proving to be a best practice.”

Burton’s institute and its umbrella organization, Community Health Councils, work to build equitable systems for health and well-being in underserved communities in the L.A. area. She has consistently felt the pushback from community residents when it comes to trusting the medical establishment, she said, a reality that long predates COVID-19.

“Because of the historical evidence that African American communities in particular have been victimized through systemic racism by our medical and health professional systems, it is very understandable that the community continues to be reluctant to participate in that system,” Burton told us in December, on the eve of the vaccine rollout. She said the reluctance extended to basic medical care, flu vaccines and other components of a health system that in other communities might be taken for granted as safe and useful.

In California, Latinos account for 55.6% of all COVID cases, and Black residents for 4.1%. But in terms of the vaccines administered so far in the state, those groups have received only 22.4% and 3.2% of the available doses, respectively.

* * *

Not all of that disparity can be ascribed to skepticism of the vaccine or the health system in general. California’s sometimes chaotic distribution plans for the three vaccines that have been used so far – Pfizer, Moderna and J&J– have left many lower income communities badly underserved, while more affluent, mostly white neighborhoods are often vaccinated at much higher rates.

But the pause on J&J doesn’t help. The vaccine was fighting a perception problem from the start, with some officials worrying that people in specific communities would object to receiving what they saw as the “third-best” medicine, based on the results of clinical trials. (In truth, all three vaccines were found to be 100% effective at preventing COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths, which for health officials is the primary objective.)

“J&J is going to be a challenge for all of us,” Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (D) predicted to the Washington Post last month. North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum (R) added that the newer product increased concerns not just of “vaccine hesitancy, but the potential for brand hesitancy as well.”

Those in community clinics and rural health facilities had high hopes for the one shot J&J vaccine, reasoning that people in hard-to-reach and underserved areas would only have to be treated one time and thus might be more open to the process. At this point, though, and with the manufacturer experiencing erratic delays in shipments and one widely publicized production plant malfunction, not enough data exists to prove or disprove that theory.

The J&J pause is going to make vaccination a tougher sell, especially in communities of color where distrust of the process was already significant.

It was six reported cases of an extremely rare blood clotting disorder, all of them occurring in women between age 18 and 48, that prompted the FDA and CDC to pause administration of the J&J vaccine until more study can be made. A similar clotting issue has caused trust in the AstraZeneca vaccine, which is not in use in the U.S., to plummet in Europe; in a recent YouGov study, people were more likely to see that vaccine as unsafe than safe in France, Germany, Spain and Italy, despite repeated reassurances from government and health officials.

A similar sort of skepticism about J&J, experts say, will only add to the difficulty they’ve had convincing people in some communities to get vaccinated – and that’s to say nothing of the existing anti-vax sentiment, as well as those who use vaccination skepticism to drive political ideology.

* * *

Given all that, calling for a pause “is a messaging nightmare,” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, a health risk communications specialist at New York University, told the New York Times. “(But) to ignore it would be to seed the growing sentiment that public health officials are lying to the public.”

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s late-March vaccine monitor, 37% of poll respondents said they would not take a vaccine, would get one only if required or would wait and see before deciding. That number was down from 44% in February and 51% in January, but the effect of the J&J pause is yet to be factored in.

In the end, Burton said, it will take a grassroots effort to convince those who are currently skeptical or fearful about taking a vaccine. That outreach needs to involve people who are known in those communities and who are understood to have their interests at heart.

“Ultimately, honesty will be the best policy, and leveraging the support of trusted voices working on the ground in communities of color is proving to be a best practice,” Burton said. “While there is a risk in getting a vaccination, there is a greater risk in not getting a vaccination. This is the honest and necessary truth that we will continue to convey to our communities.”

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

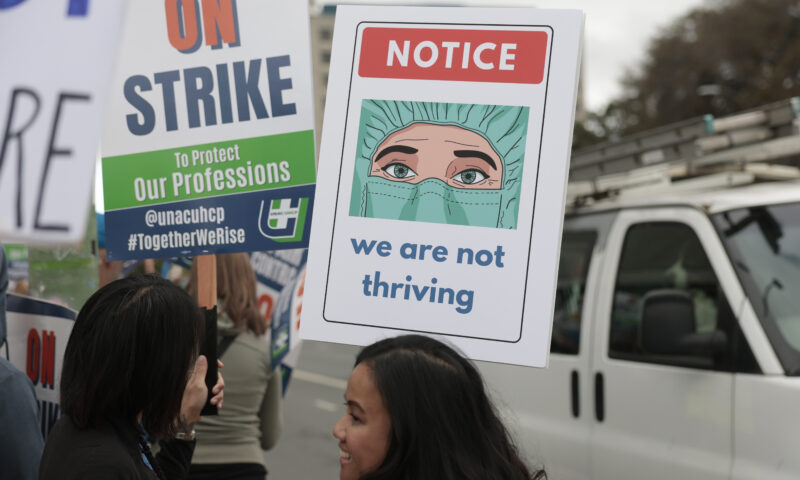

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?