Pandemic Nation

Epic Fail: For-Profit Los Angeles Hospital Closes in the Middle of Surge

A 204-bed hospital in L.A.’s Mid-Wilshire district is shuttering, despite the city’s need for intensive care beds for COVID-19 patients.

If you ever need to know why someone would argue against the “free market” concept when it comes to hospitals, medical centers or clinics, look no further than the building on the corner of San Vicente and Olympic boulevards in Los Angeles. For more than half a century, locals knew it simply as Midway Hospital. More recently, it was Olympia Medical Center.

Soon, you can call it closed — in the middle of a pandemic.

On Dec. 31, Olympia’s corporate owner, Irvine-based Alecto Healthcare, announced that it would shutter the 72-year-old hospital on March 31. Alecto’s statement indicated the move was being made “to allow for substantial renovations” in order to “better serve the healthcare needs of the community.” In truth, Alecto, a for-profit company, had already reached a deal to sell off the property to UCLA Health. The university confirmed the sale but was vague about what it’ll do with the building or the surrounding grounds.

There was a sense of outrage that any facility would prepare to close in the midst of such a massive emergency as a pandemic.

What is very clear is that a 204-bed hospital in the Mid-Wilshire district of the city is closing, despite the crying need for intensive care bed space for COVID-19 patients citywide, as Los Angeles’ coronavirus numbers continue to skyrocket. In the case of Olympia, it’s also the scheduled end of a facility whose patients are substantially minority, elderly and lower-income, and it will mark “the separation of employment” (Alecto’s words) for several hundred health care workers.

Alecto’s announcement caught local officials by surprise and left longtime users of the hospital scrambling to find what their future care might be, and where. Meanwhile, state Assembly member Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica) told the Beverly Press he would work with the California Department of Public Health on what to do if the pandemic mandates the need for the hospital to stay open past Alecto’s announced shutdown date, although it’s likely that many doctors and nurses will have moved on by then.

Across the board, there was a sense of outrage that any facility would prepare to close in the midst of such a massive emergency as a pandemic.

“How can we be having an acute-care hospital shut down by March 31 when we need hospital beds, when they’re putting up field hospitals and asking Navy ships to come back?” Dr. Don Schiller told the Los Angeles Times. Schiller, who is on the staff at Olympia, called it “a terrible public health mistake.”

* * *

It’s also almost assuredly a straight business decision, the kind that Alecto Healthcare has come to know pretty well. Last year, the West Virginia attorney general’s office announced that it was investigating the abrupt closures of two Alecto-owned hospitals in the state. West Virginia’s House of Delegates passed a resolution urging state attorney general Patrick Morrisey to look into whether Alecto violated state laws, noting that the company made a number of promises, one of which was to continue with community-based health care in the region.

In the West Virginia case, it’s clear that Alecto’s attempt to flip the hospitals from nonprofit to for-profit status was a loser, and Morrisey told the Times that as a result of his office’s investigation, Alecto has already agreed to pay hospital employees more than $1 million in lost wages and retirement benefits. But geography aside, the West Virginia hospitals and Olympia Medical Center share something in common: lower-income patients.

“When the county is so desperate to find hospital beds for the most deadly pandemic in a century, it is immoral and unconscionable to shut down a major metropolitan hospital.”

– Bonnie Castillo, California Nurses Association

According to the California Nurses Association (CNA), which staffs Olympia, Medicare reports for the first half of 2020 show that about 60% of Olympia’s admitted patients were covered by Medicare, and almost 30% were covered by Medi-Cal. Roughly 40% of admitted patients were Black, the association said, and some 63% of patients were over the age of 60. (Disclosure: The CNA is a financial supporter of Capital & Main.)

Those statistics suggest a profit-driven company’s nightmare, since federal and state reimbursements for hospital services amount to far less than do collections from private insurers. Thus, rather than being viewed as a vital local health care provider, a place like Olympia eventually is perceived on a corporate level as a drain on the bottom line.

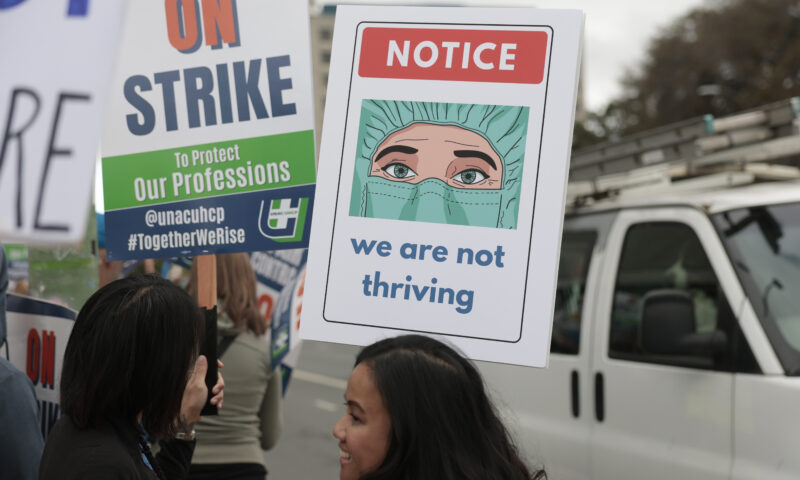

The CNA, which represents nearly 450 registered nurses who work at the hospital, said the nurses planned to “fiercely fight” the planned closure. “At a time when the county is so desperate to find hospital beds for the most deadly pandemic in a century, it is immoral and unconscionable to shut down a major metropolitan hospital,” said Bonnie Castillo, executive director of the CNA.

But it has been happening all too often. According to hospital business news site Becker’s, 47 hospitals across the country either filed for bankruptcy or closed altogether by mid-October of last year, a hideous total in light of the dire need for both regular and emergency health services in the time of COVID.

And as we’ve reported previously, rural and community clinics have been hammered, with thousands of them either temporarily or permanently closed. The clinics already had been on the run financially for years and were pushed to the breaking point in 2020, as the kinds of services that normally keep them going — routine checkups, dental appointments — all but ended so that resources could be diverted to coronavirus patients.

With Olympia’s fate abruptly sealed, Alecto’s note announcing its closure directed patients to the three nearest acute-care facilities in the area. As the Times noted, the closest of those, Cedars-Sinai, about two miles away, is already severely impacted by COVID cases. On Jan. 11, according to a dataset from the Department of Health and Human Services, Cedars-Sinai was at 136% of ICU capacity.

* * *

Attempts to talk about all of this with Alecto officials have been fruitless. Calls to the company’s Irvine headquarters went unreturned, and Alecto’s own website contains nothing — it’s “under construction.” (The company was founded in 2012.) Ultimately, though, there’s nothing new about for-profit corporations closing hospitals because they don’t churn enough revenue. It’s just particularly reprehensible in a time of utter need.

The CNA’s Castillo said the organization will work with local and state leaders to demand that Olympia remain open “for at least the duration of the pandemic,” and National Nurses United’s news release noted that the old Midway logged 25,000 ER visits in 2019. Barring a major intervention, those patients will be packing other area hospitals in a few months — the latest cost of doing business in a profit-driven health care model.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas