Priced Out

Will the Cost of Living Push Millennials Into a Generation War With Baby Boomers?

Co-published by Fast Company

It’s all about housing. And health care. And student loan debt and more. “Entitled” Millennials have had enough.

Boomers poured into the job market in the 1960s amid a wave of post-war prosperity. America’s 80 million millennials may have been born at the wrong time.

As successful baby boomers reach retirement age, plenty of them express frustration with kids today, especially millennials—those born between the early 1980s and early 2000s.

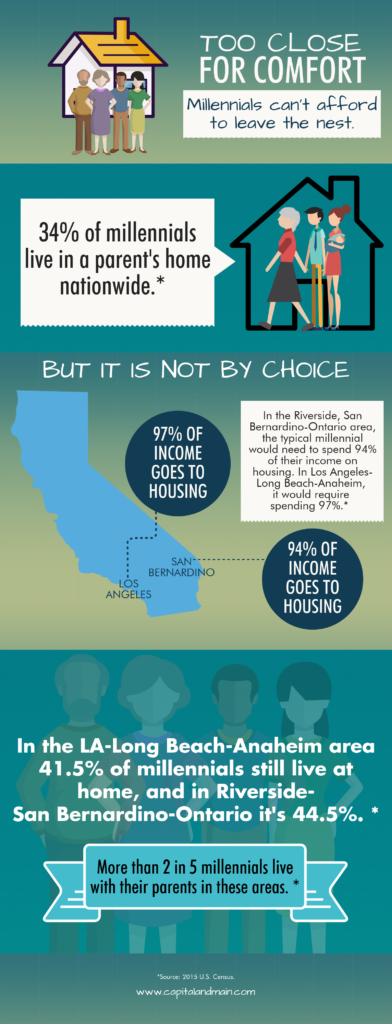

Foremost among the young adults’ alleged sins is their seeming inability to support themselves. Those kids need to develop a work ethic and save—penny by penny, like their parents and grandparents did. One day they might be able to move out of their parents’ basement or even—hallelujah—buy a home of their own.

But how soft and spoiled can young adults really be as they wrestle with historic levels of student debt, incomes that often pale in comparison to the basic costs of living—especially housing—and future prospects that appear greatly diminished compared to those of earlier generations? Dowell Myers, a University of Southern California demographer who focuses on generations and immigration, says that millennials’ critics have it backward: The people who have “enjoyed enormous advantages” throughout their lives, the baby boomers, are the truly entitled generation.

If millennials are the trigger for the housing shortage, then policy makers largely elected by boomers may be one of the main causes.

Boomers, who made up the largest generation in U.S. history in their youth, poured into the job market in the 1960s amid a wave of post-war prosperity when the country was at peak influence and wealth relative to the world. For many in that generation, the benefits came in a river of opportunity: cheap education, job security, paid vacation time, low-cost health care and lifelong pensions. Childcare and housing were remarkably affordable to most people. The result: juiced-up social mobility for tens of millions of Americans.

In many parts of California, a single salary in a typical job—teaching, policing, firefighting, construction or even gardening—could support a family and even pay off a home mortgage. Back then, working people commonly bought homes near where they worked for two times the typical annual household salary. In today’s costly market, buyers generally fork out close to eight times the median household income, signaling a huge de facto devaluation of work.

So while boomers, perhaps understandably, hype the hard work they put in to succeed, Myers says that to a certain extent, “They were simply born at the right time.”

Bad Timing?

America’s millennials—nearly 80-million strong—may have been born at the wrong time.

In California, births for their generation peaked around 1990. For many, their earliest collective memory is of the 9/11 attacks. They entered the professional world in the shadow of the Great Recession. Now largely in their twenties, their growing demand for very limited housing is a primary driver of California home prices. That is likely to continue for at least a few more years as the greatest number of millennials will turn 30 in 2020. Since migration to California from other states has turned negative, as has international migration, the coming years may well represent peak-demand on the housing front, says Myers.

Income and property tax policies (such as Proposition 13) were put into place that, however unintentionally, privileged early-arriving homeowners over others.

If millennials are the trigger for the housing shortage, then policy makers largely elected by boomers may be one of the main causes. Their own entry into the housing market in the 1970s drove a sustained surge in home prices in California.

Rather than respond with an enduring construction boom to keep housing inventory affordable, the state downshifted—implementing rules, laws and ballot measures that collectively would make it impossible to add enough housing to satisfy demand. Restrictions prevented the addition of many units around single-family homes and the replacement of many homes with apartment complexes.

Los Angeles : 1,200 rental units being built on La Cienega and Jefferson boulevards. (Photo: Eric Pape)

Income and property tax policies were also put into place that, however unintentionally, privileged early-arriving homeowners over others, encouraging more people to buy and creating more demand that, in turn, drove up prices. One such measure was Proposition 13, which amended the state constitution by a popular vote in 1978 and granted people who owned homes at the time permanent reductions in property taxes. Officially titled, The People’s Initiative To Limit Property Taxation, Prop. 13 means that a homeowner who bought in the cheap real estate market of the 1970s or earlier might now pay 10 cents in property tax for every dollar a recent buyer of a similar nearby house pays.

One effect is that longtime property owners, including many boomers, or their heritors enjoyed the benefits after Prop. 13 shifted their collective tax burden largely toward Generation X and now, on millennials as they’ve entered a much more expensive real estate market and are being taxed accordingly.

Slacking on Building

California’s current housing crisis was delayed during the 1990s due to a saving grace of sorts. Generation X, which is sandwiched between the boomers and millennials, was so small that their search for a place to live didn’t aggravate the housing shortage much.

But a common sense look at population growth at the time should have triggered policy makers to alter tax, construction and regulatory policies to facilitate an ongoing home-construction binge in urban California, especially as millennials began to reach adulthood in the 2000s.

“The victims are millennials and the boomers don’t care.”

There was what passed for a large wave of construction that decade—some analysts at the time even feared a glut, but they weren’t looking far enough ahead. And regardless, the miniature-building boom was cut short by the massive economic downturn (sparked largely by speculation in the housing market) that began in 2008. Construction ground to a halt.

A decade later, while it might seem that enormous steel cranes have become California’s new state bird, home construction still doesn’t come close to matching the natural increase in housing demand among residents. Myers says that for every two apartments or homes California currently builds, it should be constructing five to satisfy the state’s millennial-driven needs.

In recent years, Randy Shaw, the founder of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic in San Francisco, has been struck by the depth and breadth of the housing crisis he has seen in the Bay Area and beyond as the real estate market exploded.

It led him to write Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America. The book, which will be published in November, focuses on a young generation that largely cannot dream of affording life in America’s dynamic urban centers, even through renting. “The victims,” says Shaw in an interview, “are millennials, and the boomers don’t care.”

Boomers help limit the construction of new housing through zoning requirements, petitions, political pressure and lawsuits.

That may be due to the huge profits many longtime homeowners earn when they cash-out their homes. Shaw says people want to believe that the housing crisis is just something that happens based on “forces beyond their control.” But the enemy of affordable housing, he says, is often those very homeowners—not because they sell, but because they have often spent years advocating policies that make housing so unaffordable for others.

According to Dartmouth economics professor William Fischel’s Homevoter Hypothesis, homeowners have such a clear financial interest in keeping their communities up and their own property taxes down that they organize to carry outsized weight with local government.

The personal financial aspect of their efforts is not always explicit. So in places like urban or coastal California, homeowners may work against the construction of more housing for reasons ranging from aesthetics, environmentalism and nostalgia for ranch-style homes, to fear of traffic and the people who live in apartments. Their weapons include supporting zoning requirements, testifying at hearings, petitions, political pressure and lawsuits, or threats to file them.

“People can be progressive or liberal on other issues, but not on housing.”

But consciously or not, if boomers help to limit the construction of new housing, they are helping to make sure that their own homes become more valuable in a constricted market.

An irony, Shaw points out, is that many such people are acting against their oft-stated political beliefs, especially in places like Berkeley (where Shaw lives), a city whose residents’ social justice bent is legendary, although many also have a profound anti-development streak. “A part of the gentrification dynamic that hasn’t gotten enough attention,” says Shaw, “is that people can be progressive or liberal on other issues, but not on housing.”

Laura Foote is a millennial on the front lines of what is becoming a generational war over housing. The blunt-talking Foote struggled with the cost of housing in the Bay Area herself before becoming the head of a pro-housing construction movement called Yes In My Backyard, or YIMBY Action. The advocacy group, which claims 1,800 mostly millennial members, focuses laser-like on loosening restrictions and generating enough rental housing to make it affordable for people who earn old-school, middle-class salaries in the region.

Foote points to polls showing large majorities of people in the Bay Area support the construction of housing—as long as it isn’t in their neighborhoods. “People always say housing should be built in that mythical Somewhere Else, and that ‘somewhere’ ends up being nowhere.”

The result? “They are stunting an entire generation and [collectively] blocking housing for millions of people,” she says. “I hope there are enough millennials in the basement saying, ‘Hey mom, we need more housing so I can move out.’”

Comeuppance?

In generational terms, millennials can be forgiven for feeling as though earlier generations have set them up for an epic fall. But, Myers says, millennials may be well-positioned to seek—and obtain—a measure of comeuppance.

That’s because they are primed to become the largest swath of the electorate, meaning that they are increasingly capable of throwing their electoral weight around. Already, their confluence of interests with developers and relevant labor unions seem to be generating activity in state capitals such as Sacramento to reduce or eliminate limitations on the construction of housing, particularly along rail lines.

But regardless of a direct electoral confrontation between aging boomers and rising millennials, home-owning boomers may face unexpected demographic trouble in the housing market down the road. After all, boomers and the home-owning survivors of the “Greatest Generation” that preceded them own more than half of all homes.

Myers says that as boomers reach their eighties—the age when people often sell their homes (as they downsize into smaller houses closer to their adult children or enter senior care centers)—they may discover they have waited too long.

The reason: Many millennials, weighed down by debt and lesser incomes, may have moved away from coastal cities in search of a more affordable life, or they won’t have been able to save enough to buy the costly homes of boomers.

Current trends suggest that migration from other parts of the country or abroad might not fill the gap either. So fewer people able to buy homes could translate into too much supply—and a big drop in home values.

“Now there is a shortage of inventory, in the future there will be an excess—unless we change things,” says Myers. “Ultimately, there is a day of reckoning coming. … Who will buy their house? Young people? … My valuable house is only valuable when I sell it.”

The safe options, he says, are either to sell it now, or for society to invest in the next generation so they can prosper—and then buy boomers’ homes when the time comes.

He pauses for effect. “I think that the older folks haven’t thought that through.”

Read more of our “Priced Out” series here. Please join Capital & Main’s Facebook group on the cost of living in California to discuss problems and practical solutions.

And follow Eric Pape on Twitter @ericpape, and let him know if you have a powerful story about the human impact of high prices in the Golden State.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Striking BackApril 12, 2024

Striking BackApril 12, 2024Organizing the Slopes

-

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024California Often Leads Change, but Not for Single-Payer Health Care

-

Feet to the FireMarch 29, 2024

Feet to the FireMarch 29, 2024New Mexico Governor Vetoes Tax Break for Wells After Pushback

-

The Heat 2024April 15, 2024

The Heat 2024April 15, 2024Climate + Young Voters = Biden Victory, Right? It’s More Complicated Than That.

-

Striking BackApril 26, 2024

Striking BackApril 26, 2024At Occidental College, Upcoming Vote Reflects Rise in Undergraduate Labor Organizing

-

The Heat 2024April 1, 2024

The Heat 2024April 1, 2024The Way-Down-the-Ballot Races That Could Transform Energy Policy for Millions

-

The SlickApril 16, 2024

The SlickApril 16, 2024On the Chopping Block: California’s Climate Program for Low-Income Housing

-

Extreme WealthApril 2, 2024

Extreme WealthApril 2, 2024Extreme Wealth Is on the Ballot This Year — Will Americans Vote to Tax the Rich?