Education

Orange County Parents: Change Name of School That Honors Klan Member

There are over a dozen streets, parks or monuments in Orange County named after former Klan members — and one elementary school.

All Mike Rodriguez initially knew, when he Googled “William Fanning Elementary Brea” a few years ago, was that it was a good school in the affluent North Orange County city of Brea. He was interested in enrolling his son there after hearing positive things about its music program from his wife’s cousin.

But Rodriguez’s mind changed when the search results showed a photo of a man standing in front of Fanning’s marquee, dressed in a Ku Klux Klan robe.

The picture accompanied an OC Weekly article I wrote in 2013 titled “Welcome to Ku Klux Kounty!” that documented streets, parks and schools in Orange County named after local pioneers who belonged to the Invisible Empire during the 1920s. I based my research on the era’s OC Klan membership rolls on file at the Anaheim Heritage Center.

One of the names listed? Fanning, a former Brea teacher and school superintendent.

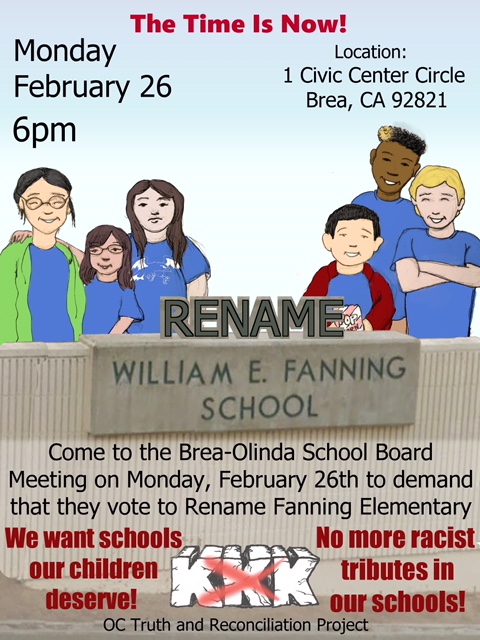

The revelation left Rodriguez “floored.” He and other parents will protest before the Feb. 26 board meeting of the Brea Olinda Unified School District and demand that trustees rename the elementary school.

For now, Brea Olinda Unified is resisting any Fanning name change. A report on the matter commissioned by school superintendent Brad Mason and obtained by Capital & Main dismisses the parents’ concerns as “editorial commentary.”

But Rodriguez is undeterred. “There was a whole dark side of Brea that was still being hidden,” says the Santa Ana Unified School District teacher. “It’s time to uncover the cover-up.”

In August, Rodriguez and other area residents created the Rename Fanning Committee. They pamphleted outside the school. And they dug further into Brea’s past, both online and through the Lawrence de Graaf Center for Oral and Public History at California State University, Fullerton. Rodriguez learned how the Klan once held a majority of the Brea City Council’s seats. That residents had long admitted Brea used to be a “sundown town,” the name given to municipalities that banned African-Americans from its city limits after sunset. And that current residents downplayed the city’s Klan past by claiming the group wasn’t necessarily racist.

The committee’s actions come at a time when local residents are finally, slowly challenging Orange County Klan and Confederate roots. These go deep: OC seceded from Los Angeles County in 1889 with the help of Assemblymember Henry W. Head, who had belonged to the original KKK under Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The committee’s actions come at a time when local residents are finally, slowly challenging Orange County Klan and Confederate roots. These go deep: OC seceded from Los Angeles County in 1889 with the help of Assemblymember Henry W. Head, who had belonged to the original KKK under Nathan Bedford Forrest.

There are over a dozen streets, parks or monuments in Orange County named after former Klan members. But last summer, the general manager of the Orange County Cemetery District announced he wanted a Confederate monument removed from the Santa Ana Cemetery in the wake of the Charlottesville tragedy. (It remains standing.) In November, the Anaheim Union High School District voted to remove any Dixie references from Savanna High School, whose nickname is the Rebels and which used a caricatured Johnny Rebel as a mascot and the Confederate battle flag at school events for decades.

Minutes of the Oct. 9 Brea Olinda Unified board meeting state that Superintendent Brad Mason said he’d asked Linda Shay, museum curator at the Brea Museum & Historical Society, to investigate the Recall Fanning Committee’s claims. Mason did not respond to a request for comment; Shay declined to share the report.

The 12-page study claims that modern-day historical “revisionism” inserts a “bias that is out of context…and therefore and quite often inappropriately judgmental in nature” to past events. Shay wrote that the authenticity of the OC Klan membership list at the Heritage Center “cannot be substantiated,” even though academic papers have cited it for decades and it was donated by longtime Orange County historian and former Anaheim City Attorney Leo J. Friis.

Shay also dismissed the multiple oral histories that mentioned Brea was a sundown town because she couldn’t find proof of a formal ordinance on the city’s website. But she did discover an oral history where Fanning’s son denied his father’s Klan ties, and “numerous sources that claimed Mr. Fanning was a selfless, compassionate and dedicated educator.”

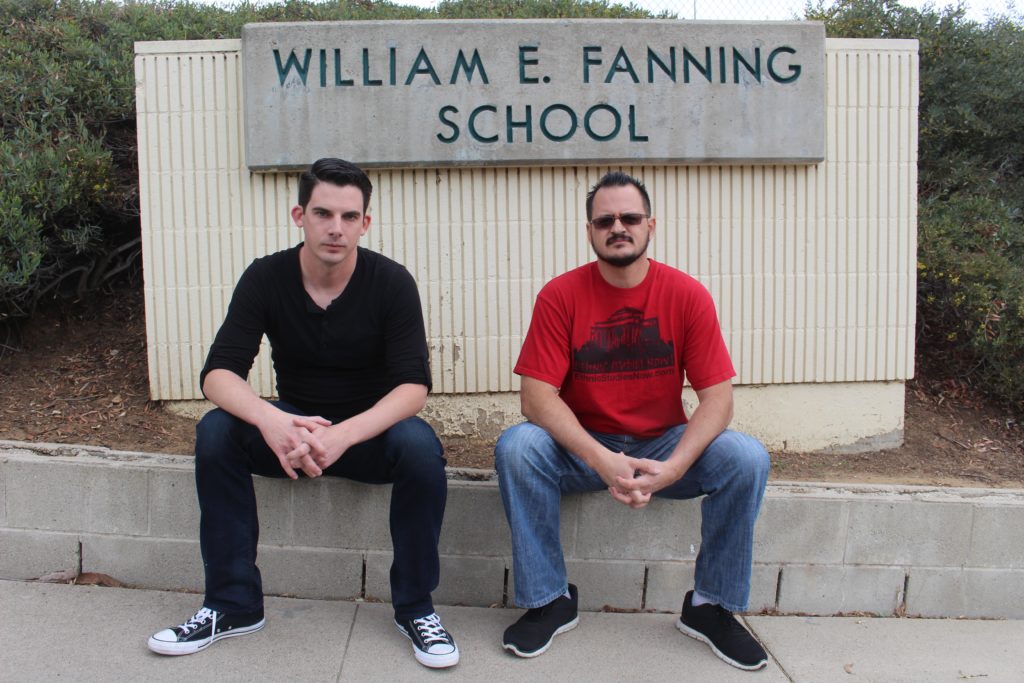

Shay’s findings amuse Recall Fanning members, who are gathered at Fanning Elementary one Saturday morning. “Unless you’re a family member, why are you championing his cause?” asks Wendy Dotan, who has lived in Brea in 13 years. “You have to question the motivation for resistance.”

“They say Fanning wasn’t directly involved with racist acts,” Rodriguez adds. “Well, he was never involved with ending them, either.”

“This school has shown us nothing but love,” says Ben Van Dyk, a history teacher at Servite High School in Anaheim. His son is a first-grader at Fanning. “The name tarnishes that love. It doesn’t represent that inclusion we’ve found here.”

Rodriguez and Van Dyk’s sons chase after a beach ball across the Fanning parking lot. “See that?” Van Dyk says. “They’ve never met until today, and yet they’re playing. In the 1920s, this would never be allowed.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care

-

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026Agents In ICE Shootings Made Racist or Sexist Remarks, Records Show

-

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026As Climate Crisis Upended Homeowners Insurance, the Industry Resisted Regulation