Living Homeless in California

Living Homeless in California: Finding Shelter — Veterans Are Broke But Not Broken

Homeless veterans live solitary and nomadic existences. At night, some sleep in cars parked near VA facilities, under freeway overpasses or in public parks.

“I don’t think any veteran wakes up and says, ‘I want to be on the street,'” says one ex-Marine.

Jack Rumpf sits on a circular bench at the corner of Wilshire and San Vicente boulevards in West Los Angeles, and talks about ghosts. Wearing a long white beard, dirty sweatpants, white socks and slippers, he turns and sweeps an arm towards the empty spaces next to him. “There used to be 15 or 20 people sitting with me here,” he says, lowering his voice to a melancholic whisper. “They are all dead now.”

Rumpf says he is a Navy veteran, a brother of five sisters, an observer of our current political scene and a lover of dogs. He is also homeless and has been so almost three decades.

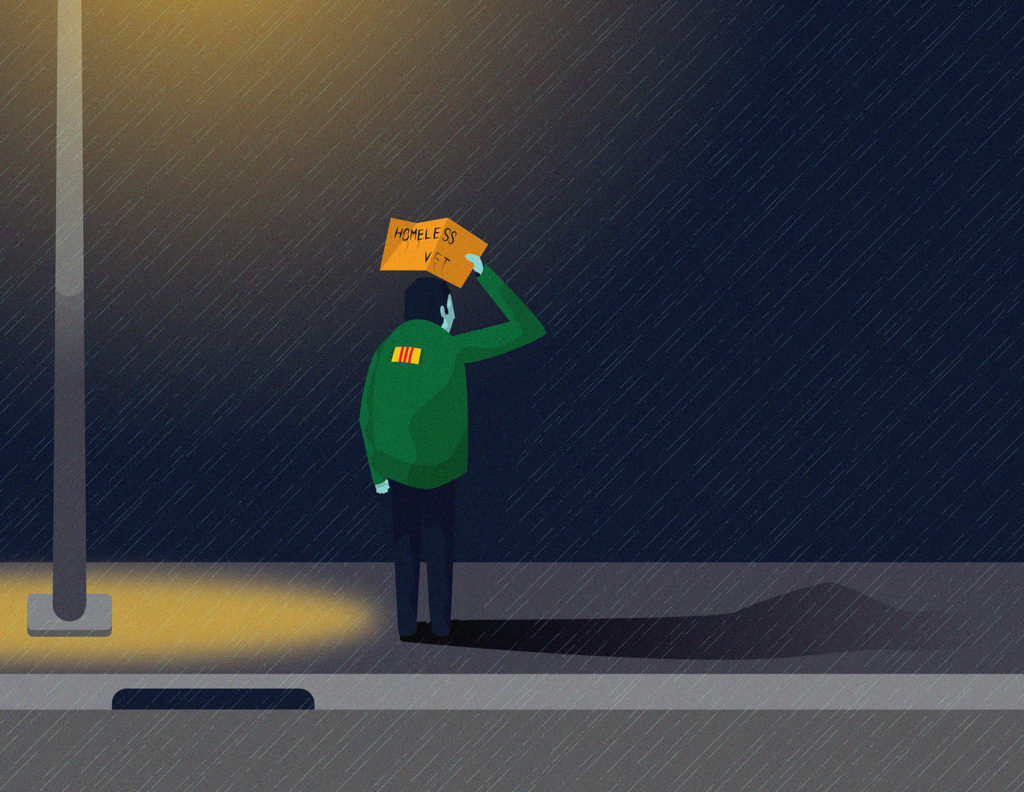

Every morning he drives his beat-up Mustang from where he parked it at night to sleep, and finds a space near the Veterans Affairs hospital. Rumpf “flies a sign” – a placard asking for money – at a Wilshire Blvd. intersection. He says that Dan Aykroyd, Whoopi Goldberg and Robin Williams have given him money, and that he has the process down to a science. “There are 30 cars at every light, which lasts 2.5 minutes,” he points out. “If half the cars give me a quarter that’s over $40 an hour.”

His beloved dog, Layla, perched in the driver’s seat, watches over the car a few yards away.

The 59-year-old Rumpf says he’s “done every damn drug that’s been known” and regards homelessness as “pretty much my fault.” He became homeless 28 years ago when he lost a job. He takes antibiotics, has high blood pressure and uses an inhaler for asthma. He caught pneumonia three times in one year. “I’m not young anymore so I have a hard time enduring the elements.”

“Mental health is not like breaking your leg, where everyone can see it.

Unaddressed, it gets worse.”

Rumpf is one of nearly 5,000 homeless veterans in Los Angeles County. Those on the Westside sleep under overpasses beneath the San Diego Freeway, on the sidewalk near the VA or tucked in vacant doorways along Wilshire or Santa Monica boulevards. When hearing their stories, there is often the suspicion that they might be tampering with the evidence of their own lives, as if they were struggling to sort out the “facts” of their personal stories.

Harry Shaw beds down each night near an ally at Park and Speedway in Venice, just yards from the beach. He embraces a strict moral code about what he will and will not do to feed himself and his dog Lulu, who he calls “part of my soul.”

“I’ll starve before I’ll eat anything gross,” he says as he eats the last of a bag of jellybeans he was given. “I won’t eat out of the garbage and I won’t sell my body, and Lulu eats before I do. I may be broke but I’m not broken.”

Shaw alleges that he was medically discharged from the Army with less than full benefits after 23 years of service because he couldn’t reach what he says was a 160-pound weight requirement for a person of his height, although published Army height-to-weight ratios contradict his claim. He is 5 feet 8 inches tall. “I could eat like a horse or eat 20 meals a day but I would only reach 155 pounds,” he says.

A veteran of the Iraq War, he is suing Veterans Affairs for full benefits but meanwhile collects nothing, refusing to take the 35 percent he says the VA offered. “The VA destroys the vets,” he says.

Shaw drove a car from Tennessee to San Francisco, sold it and took a bus to Los Angeles. Now he flies the sign every morning near the Santa Monica Pier. According to his moral logic, panhandling is when you ask someone, “Can you spare some change?” while flying the sign is work.

Also Read These Stories

He recently made $2 during a six-hour period, a daily ritual that he calls his “mission.” He wanted a slice of pizza but the cost at the local pizza joint was two dollars plus tax, so he bought a can of food for his dog instead. “The hardest part is finding a place to clean yourself,” he notes.

If offered housing assistance by the VA Shaw might consider it, but he prefers to sleep on the streets and fight for his full benefits. “I’d rather have a recreational vehicle where I can go wherever the heart and mind desires,” he says.

Shaw’s antipathy towards the VA is not atypical for homeless veterans. For whatever reason – bureaucratic hurdles, negative staff or physician interactions, or the vet’s own contributions to an already difficult situation – complaints abound.

The VA is now planning 1,200 units of permanent housing for homeless veterans.

The original purpose of the West Los Angeles land that was donated to the federal government in 1887 was to house homeless veterans. Over the years, however, VA budgeting priorities directed towards the hospital and questionable land leases left the campus dilapidated and underutilized.

As a result of a 2011 lawsuit filed on behalf of homeless vets initiated by local attorneys and the American Civil Liberties Union, the VA is now committed to repurposing the 388-acre campus, located near the 405 Freeway, to house veterans.

Jesse Creed, executive director of Vets Advocacy LA (a party to the lawsuit), believes the land could house every homeless veteran in Los Angeles County. “It’s as much land as UCLA, which has 45,000 students,” he says.

The VA is now planning 1,200 units of permanent housing for homeless veterans. A private sector developer is being chosen to finance construction and operate the housing facility.

Monte Williams is one of 54 veterans who currently live in permanent housing on the VA campus. An ex-Marine, he describes becoming homeless as a “process.”

“I don’t think any veteran wakes up and says, ‘I want to be on the street,’” he says. Williams lost his job when mental health issues got the best of him: “Mental health is not like breaking your leg, where everyone can see it. Unaddressed, it gets worse.”

One L.A. vet pushes a shopping cart filled with his tent and other belongings half a mile up a small hill to make his hospital appointments.

Williams, who became homeless in 2010, had an epiphany while looking to buy alcohol near the VA hospital. “Another older homeless veteran I was with pointed to the hospital and told me to go to the emergency room and my sanity just came back,” he says with tears in his eyes.

He is appreciative of the programs and housing that the VA has provided and now helps his new family — other homeless vets. “My daily life is sharing my story with other veterans…helping them gain their life back.”

Donald Leslie Peterson sleeps under the 405 Freeway. The story that he tells about himself is difficult to follow. He says he was shot during a rescue mission in Panama in 1989, that he has two Purple Heart medals for wounds suffered in Afghanistan and Syria, and that he was on protection duty 30 feet behind John F. Kennedy’s car in Dallas.

Peterson takes the medication Abilify (prescribed for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) and says he stays close to the hospital so he can see his social worker and apply for housing. “Unless I sit down and think about things, my thinking gets a little bit crowded,” he says. He pushes a shopping cart filled with his tent and other belongings half a mile up a small hill to make his hospital appointments.

“Parents tell us we scare their children but I think the parents are scared more than the children.”

He becomes animated when he talks about his family — two girls who, he says, attend UCLA and visit him every other night. “The biggest challenge is keeping the bond of my family together,” he says. “It’s hard not being able to sit down with my family and have a meal. I mean, we sit on buckets and crates and joke and play, but when you come right down to it, it’s not funny.”

Heidi Marston, Director of Community Engagement and Reintegration Services at the Greater Los Angeles VA, believes that the VA has a program and approach that can reach homeless veterans where they are. “We use a housing-first approach, which means that housing is the first step for you. There are no barriers to getting into housing … so you don’t have to be sober and you don’t have to be in treatment,” she explains.

Asking a homeless veteran what they think the future holds for them is a way of asking about the kind of life they want — or fear.

Marc Cote, a five-year Army veteran who lives in a tent in Westwood Park, a few blocks from the VA hospital, wants to be left alone. Cote pushes himself around backwards in a wheelchair, using public bathroom sinks to clean up — what the homeless refer to as “birdbaths.” Parents walk by holding their children’s hands heading to soccer games and tennis matches. “The parents tell us we scare their children but I think the parents are scared more than the children,” he says.

Park rangers patrol the ground and sometimes demand that Cote take his tent down before 6 a.m. “I would be happy to stay here if they would leave me be,” he says one recent Saturday afternoon. “I don’t make a mess or argue or fight or throw things.”

It will take years until the 1,200 planned residential units are complete. Meanwhile thousands of veterans will remain on the street, finding food, shelter and companionship where they can.

Jack Rumpf remembers an incident from when he was flying his sign at a stoplight in Brentwood. “The guy pulled a gun on me and didn’t shoot. I said, ‘You schmuck, why didn’t you shoot me? If I was dead this would be all over.’” Rumpf believes that his near future is “leaving this world.” For now he settles for a safe parking space at night for himself and his dog.

Monte Williams, who has housing, feels an urgency towards his fellow veterans. “I refuse to believe that any veteran, or any human, wants to be on the streets,” he says. “Something has to happen, so I just want society to know – to try to understand.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.