Living Homeless in California

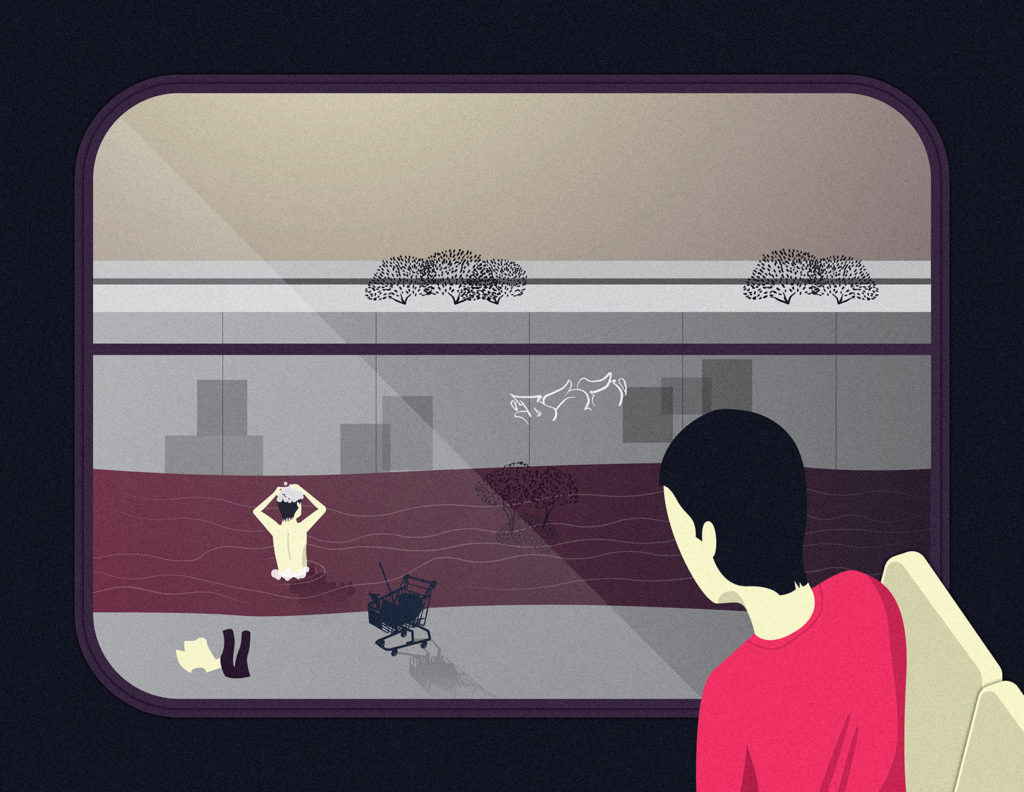

Living Homeless in California: Dignity Is a Hot Shower

Facilities that provide showers and clean clothes encourage the homeless to seek health services and permanent supportive housing.

For Los Angeles County’s homeless, a shower and clean clothes are more than a hygiene issue. They’re a matter of humanity.

Eric Finister feels fresh. As fresh as a chronically homeless man can feel. The 53-year-old has just emerged from the showers at a Lava Mae portable trailer parked alongside Mount Tabor Missionary Baptist Church in South Los Angeles, and he looks sharp: his soft face glowing, salt-and-pepper beard trimmed and wearing new clothes.

For a moment, he can forget about the crowded, trash-strewn reality of Western Avenue and the hustle that exist only a few yards away.

“This is what helps,” Finister says. “I count this as a blessing to be able to come get a shower, have some fresh clothes and a meal to eat. This helps me along the way until I get back to where I know to be, and when I do, I will never forget this place.”

Also Read These Stories

For the roughly 53,000 men and women in Los Angeles County who don’t have permanent housing (and for some who do), a shower and clean clothes are more than a matter of hygiene. They’re a matter of humanity. Cleaning up can dissolve the separateness between a homeless person and the rest of society. It’s a door through which some will come to mental health services, substance abuse counseling, church and other community contacts and, finally, housing.

Lava Mae calls it “radical hospitality,” and it’s in very short supply in Los Angeles. The privately funded group runs two trailers with three showers each on a daily schedule around town. The city operates one similar trailer at the Skid Row Community ReFresh Spot on Crocker Street downtown; the other option is shelters, which are avoided by a significant number of the homeless.

If L.A. County were a refugee camp, by United Nations standards its number of public showers would be considered woefully insufficient.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees’ standard for displaced-persons camps is one shower for every 50 people; if we think of Los Angeles County as one giant refugee camp, that would mean about 1,140 showers. A 2017 study looking at the lack of toilets on L.A.’s Skid Row (nine public toilets for roughly 2,000 people at night) also found a “scarcity of showers.”

“[The shower] transmits that we care about you and that you have dignity as a human being,” says Paul Asplund, Lava Mae’s director of partnerships and development. He’s a big, voluble guy with a graying beard who was once homeless himself 30 years ago, and has since had several successful careers.

“We notice a change when people emerge from the shower,” Asplund adds. “They’ve pressed the pause button on a chaotic life. They’ve had 15 to 20 minutes of privacy, peace and hot water, clean towels and some products. We know that has got to improve their health, if only from a psychological aspect. We haven’t quantified this in a larger way, but we’re not a health mission. We’re on a dignity mission.”

Asplund finds Lava Mae’s “guests” are more likely to seek out the other resources available at Mount Tabor. His job is to bring together partners like those at this church, where folks seeking showers also find food, clothes, and representatives from the L.A. Homeless Services Authority, the Department of Mental Health, Mount Tabor’s ministry and others who can put them on a path to housing.

Finister’s story is not unusual: He grew up in Compton, the youngest of 10 children. He has worked in warehouses, but his last job was doing homecare for his elderly parents after they moved to a rented trailer in a mobile home park in neighboring Paramount. Several years ago a funeral for one of his sisters put his parents behind on rent, and when they got evicted and went to assisted living, Finister ended up on the street. He crashed with various friends and lived for a while in Long Beach’s Bixby Park. He has adult children but, he says, “I can’t go to them like this.” He’s currently on the county’s general relief program and is staying at a shelter on Western Avenue called the Testimonial Community Love Center. He wants to work and to have a permanent home, and to get them he needs a positive outlook. The shower helps.

Lava Mae staff greeted a man who looked like an apparition, his clothes blackened and stained. “Hook me up!” he said, motioning to a shower.

“When I came last Wednesday, they got jazz! Man, I’m like, ‘Oooh! I can get with this!’” he enthused. The custom-built Lava Mae trailers have three complete bathrooms, each with a toilet, sink and shower, cleaned after every use and stocked with donated products. “I can take my time, lather up, and do what I gotta do and come out: Ta-da!”

Bernice Noflin, Mount Tabor’s outreach coordinator, notes that committing to help the homeless has created new energy in the church.

“What I didn’t expect was the benefit to our ministry, to the people working in this church,” she says. “Purpose is huge. Sometimes it’s what keeps you alive. It’s healing for all.”

As Finister and I talk on the sun-baked sidewalk, a slow parade of men turn up. One of them comes like an apparition, his very identity lost in clothes blackened and stained, a man to whom polite society would give a wide berth. The Lava Mae folks step forward and greet him. “Hook me up!” he says, motioning to the trailer.

On another day, Ismael Godinez, a caseworker with Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System, or HOPICS, is operating out of its South L.A. office. As he drives out in a van to do some intake paperwork with a single mother with five kids, and who is living out of her old SUV at Ted Watkins Memorial Park, Godinez tells me that he already has an appointment later in the week to drive another client to the Lava Mae showers.

“He wasn’t using all our services, but when I mentioned that I could get him a shower, his eyes lit up,” says Godinez. “He was, like, ‘Oh, I’d like that.’”

People find showers anywhere they can or take “birdbaths” — washing up at a sink in a restaurant or gas station.

Having a shower to offer, like a meal or a fresh set of clothes, is a chance to connect. On the drive over, Godinez says he hoped to win a little more of the man’s trust. He related another case where one of their clients had an opportunity to go for a job interview, and one of the mental health workers let him borrow a suit, and he got the job.

John Helyar, manager of the outreach teams at HOPICS, says that his group doesn’t get that much demand for showers or laundry. People find showers elsewhere or take “birdbaths” — washing up at a sink in a restaurant or gas station — and when they need clothes they get them from clothing giveaways. His teams get people to showers when they want them, but that need is dwarfed by the most obvious one: housing. That remains the big roadblock, two years after voters approved a massive housing ballot initiative. “HHH was passed in November 2016, so barely anything has come online yet, and it’s going to be a while before it [does],” Helyar explains.

Still, in places where homeless encampments are dense or services simply scarce, the showers are a draw.

L.A. Metro plans to put bathrooms and showers in some of its 93 rail stations.

“Bringing these mobile showers or the ReFresh Spot on Skid Row really gives us a tool for engagement teams,” says Celeste Rodriguez, homelessness policy coordinator in the Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity. “At the end of [the shower], there’s another moment of engagement to connect them to outreach teams, which get them to services and ultimately to long-term housing, which is everyone’s goal.”

The city’s ReFresh Spot project, launched in December 2017, is already very popular with the homeless. It is currently transitioning to its second phase, which will see three trailers offering more than a dozen showers, toilets and a set of clothes washers and dryers.

“It’s not just a porta-potty,” says Zita Davis, executive officer at the Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity. “It includes what we call ambassadors; they serve as kind of outreach folks. They welcome anyone who wants to use the facilities. They also direct them to professionals who are on site, if they need additional services. There’s always a clinical person who’s on site and can help with referrals. And they can make connections, to try to develop a plan for them so that they can ultimately end up in housing.”

Other public agencies are also seeing the need. The L.A. Metro board of directors voted recently to create a plan for putting bathrooms and showers in some of the 93 existing Metro stations, the first two appearing at the North Hollywood and the Westlake/MacArthur Park Red Line stations.

“It’s not a business that the city has been in, providing temporary showers and toilets,” says Davis. “These are some of the innovative ideas and projects that the city has put forward to try and bring dignity to folks who don’t yet have housing. Building infrastructure takes longer, so this is an approach to addressing needs today.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care