Latest News

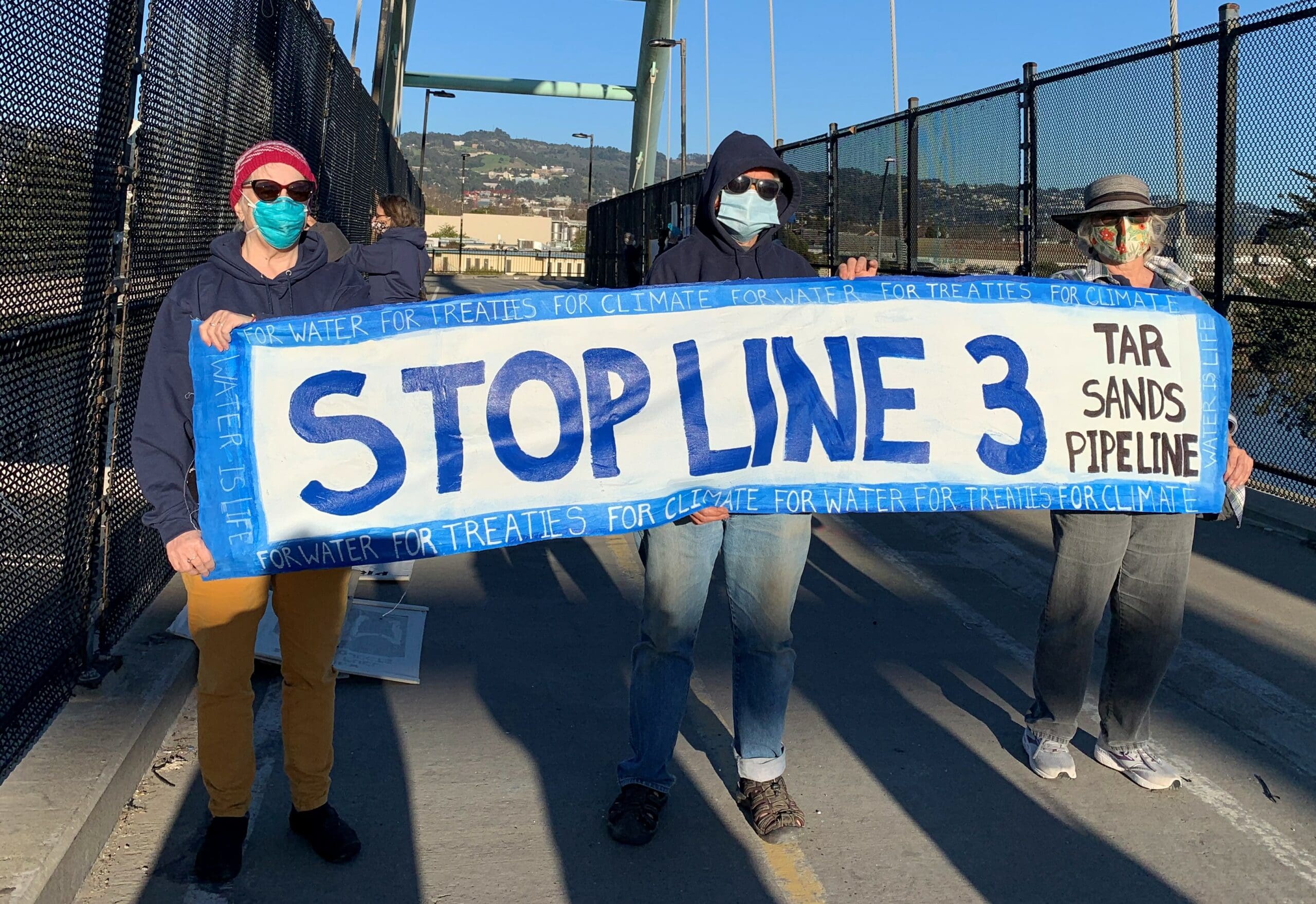

Grandmothers and Indigenous Groups Join to Block a Pipeline

Nancy Feinstein and Carol Rothman first started organizing older women in 2016—a demographic they see as an under-utlized resource.

“The last place I wanted to be was watching them tear apart my forest limb from limb—it was just devastating,” said Winona LaDuke, the White Earth Tribal member and economist leading the resistance to a $2.9 billion pipeline construction project in northern Minnesota. The operation, which broke ground last December, will replace parts of an aging pipeline carrying nearly a million barrels of tar sand from Alberta, Canada, to Wisconsin and construct Line 3, a new pipeline corridor.

Co-published by Patch

Opposition to Line 3 from Indigenous communities and residents across Minnesota has grown over the past seven years. Community members and activists feel the project poses a significant threat to public health, natural resources and Indigenous treaty rights. Only five years ago, in 2016, the same natural gas company, Enbridge, paid $177 million in penalties and improved safety measures for a pipeline rupture—the Kalamazoo River oil spill—one of the largest inland oil spills in U.S. history.

Some fear Line 3 could have a similar fate. “Enbridge has the tiara for the most oil spills and the worst oil spills,” said LaDuke, who has served twice as a Green Party candidate for vice president. The proposed line would run directly across 200 water bodies and 78 miles of wetlands as well as through Ojibwe land in violation of treaty rights. Indigenous leaders and organizers are calling on President Biden to block construction as the Obama administration did for the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL).

The proposed line would run across 200 water bodies and 78 miles of wetlands — and through Ojibwe land in violation of treaty rights.

“Please Enbridge, change course. We do not need Line 3, we need clean water and clean air,” said one woman in a video from the #StopLine3 demonstration last year. Since construction began, demonstrations have been staged across the state, at the Enbridge office in Park Rapids, Minnesota, and at construction sites, reminiscent of the opposition to Standing Rock but without the international media coverage. The most notable endorsements supporting the resistance came from Rep. Ilhan Omar and Jane Fonda.

In response to questions for this story, an Enbridge spokesperson emailed a statement that called Line 3 “the most studied pipeline project in Minnesota history,” with “more than six years of science-based review by regulatory and permitting bodies.” The statement also said, “Enbridge has demonstrated ongoing respect for tribal sovereignty” and that its project “is already providing significant economic benefits for counties, small businesses, Native American communities, and union members.”

Beyond the spotlight, however, grassroots-level organizing runs deep. Water Protectors—mostly residents from across the state —have camped out along the pipeline through the freezing, Minnesota winter months to oppose construction and protect the region’s water from pollutants. Their efforts have not gone unnoticed. One demographic across the U.S. has taken up their cause: grandmothers.

* * *

In January, Carol Rothman and Nancy Feinstein, self-identifying as Jewish grandmothers in their early 70s, raised nearly $15,000 from their home in Berkeley, California, to support female, Indigenous elders at the Line 3 demonstrations. Through personal connections, they met LaDuke, also a grandmother, and had all proceeds go to her nonprofit organization, Honor the Earth.

Feinstein and Rothman first started organizing “grandmothers” in 2016—they see the demographic as an underutilized resource. “Media stereotypes of activism exist, and it is usually the younger groups who ultimately represent a movement,” said Deana A. Rohlinger, a professor of sociology at Florida State University. Feinstein and Rothman set out to create their own space in the climate justice movement. “We’ve got time; some of us are retired,” said Feinstein, and many bring years of political activism to the table, having come of age in the ’60s. “That still is a sleeping giant,” said Rothman.

From the Gray Panthers to Portland’s Wall of Moms, older women have a long history of social activism.

At their first meeting in Rothman’s living room where 12 grandmothers congregated and one Skyped in from Standing Rock, they decided to organize around DAPL. Working in tandem with indigenous elders at Standing Rock, they held rallies, direct actions and fundraisers in Northern California. It was the beginning of a trusting relationship with Native American grandmothers in South Dakota, which was further strengthened through a personal friend of Rothman’s, Madonna Thunder Hawk.

Thunder Hawk is part of an informal group of grandmothers on the Cheyenne River Reservation who call themselves Wasagiya Najin, meaning “Standing Strong” in Lakota. Through the initial friendship, Wasagiya Najin has become “our sister grandmother group,” said Rothman.

“The fact that they were there, hands on, doing things in support of Mother Earth, it’s just an automatic kinship,” Thunder Hawk said.

“We do support, because that’s what we had when we were young. We had our founders who supported us. They gave us so much strength to do what we had to do,” Thunder Hawk said. And that’s the role they serve now as elders, she said.

The Native American grandmothers have visited the Bay Area a few times since, organizing joint fundraisers and educational workshops on climate change and its impact on reservations. Through personal relationships and a shared concern about future generations, an underground network of politically engaged older women is growing across the country.

* * *

According to Deana Rohlinger, older women actually “have a long history of activism.” The Gray Panthers were an advocacy group founded by older women fighting ageism and other forms of discrimination who achieved national notoriety in the 1970s. But their activism received less press than the youth movements at the time. In the decades following, new organizations have leaned into their image as older women.

Raging Grannies, an activist group most popular in the ’80s and ’90s, were known for dressing up in clothes mocking stereotypes of grandmothers and breaking out into song at protests. While attention-grabbing, they have not helped society move beyond stereotypes of older women, said Rohlinger. More recently in Portland, a group of mothers who call themselves the Wall of Moms demonstrated at Black Lives Matter protests and tried to use “their whiteness and status as a mother” to de-escalate confrontations with the police. “But it didn’t keep them from getting pepper-sprayed,” Rohlinger noted.

There are significant advantages to banding together however, experts have claimed, given the political sway the grandmothers have as seniors and their intersecting privileges.

Today more than 1,000 grandmothers across the Bay Area have joined in, calling themselves 1000 Grandmothers for Future Generations. They are not registered as a nonprofit organization though, because “we want to be as political as we want to be,” said Feinstein—and the group has already seen success. They helped oppose a pipeline project in the San Francisco Bay, and most recently raised more than $194,000 for the 2020 U.S. Senate races in Georgia.

“We don’t have spaces where older and middle-aged people come together with younger generations to discuss political activism. They don’t exist normally in our society,” said Deana Rohlinger.

While political activism is on the rise across all ages, intergenerational conversations about activism remain rare, experts said. “We don’t have spaces where older and middle-aged people come together with younger generations to discuss political activism. They don’t exist normally in our society,” said Rohlinger.

Early on, the founders of 1000 Grandmothers said they made a commitment to work alongside Indigenous and minority communities, as well as people across the age spectrum. “We want to make sure that we are in support of people of color and youth leadership, as opposed to telling everybody what to do,” said Feinstein.

Their priority in 2021 is stopping Line 3. Feinstein noted that Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is extremely invested in the pipeline, and Biden has remained silent on the issue thus far. Their relationship “is going to be very tried by this particular resistance to this particular line,” she said.

Rothman and Feinstein are tentatively planning a trip with grandmothers from the Bay Area, grandmothers from Minneapolis and Indigenous grandmothers from tribes around the country to join the Water Protectors at Line 3 in northern Minnesota next month. Many of them already received their COVID-19 vaccine—a protection most younger folks don’t have.

Grandmother Winona LaDuke is in full support. “I have really pulled on grandmothers to come,” LaDuke said. “We are encouraging older women to join us for our children…We actually think that it’s safer to be an older white woman getting arrested or getting charged than a young Indian man.” She herself has six charges pending against her for demonstrating against Line 3, including unlawful assembly and attendance at unlawful assembly. “They’re trying to characterize us as criminals,” she said.

Rothman and Feinstein have also been arrested at nonviolent direct actions in the past and said they are willing to be again. “I feel like we have earned a place in the [climate] movement—one of respect—that wasn’t there when we were just individuals showing up at things,” Feinstein said. “Like every marginalized or partially marginalized community, when you start speaking collectively, you have a different voice than when you’re speaking as individual, gray haired old people. And that’s been a powerful transformation.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsNovember 19, 2025

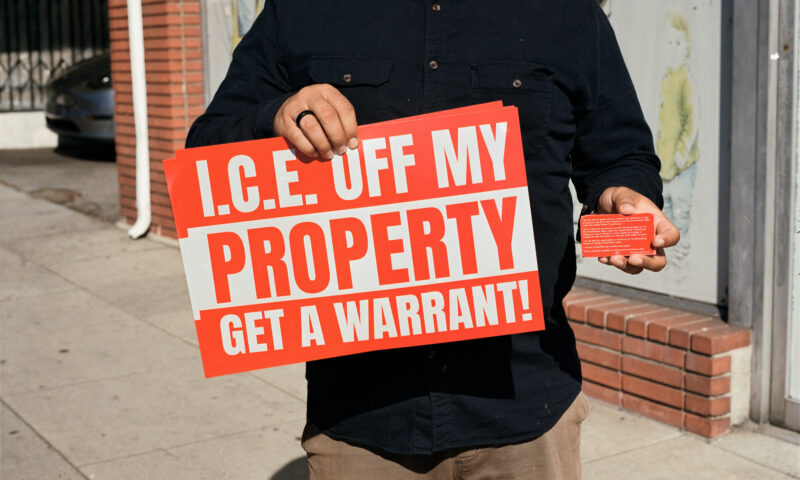

Latest NewsNovember 19, 2025How Employers and Labor Groups Are Trying to Protect Workers From ICE

-

The SlickNovember 18, 2025

The SlickNovember 18, 2025After Years of Sparring, Gov. Shapiro Abandons Pennsylvania’s Landmark Climate Initiative

-

StrandedNovember 25, 2025

StrandedNovember 25, 2025‘I’m Lost in This Country’: Non-Mexicans Living Undocumented After Deportation to Mexico

-

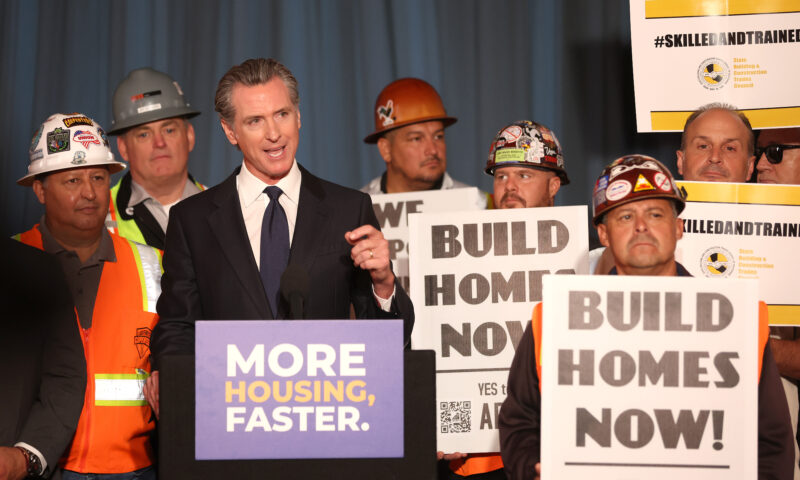

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025

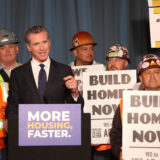

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025Seven Years Into Gov. Newsom’s Tenure, California’s Housing Crisis Remains Unsolved

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025Santa Fe’s Plan for a Real Minimum Wage Offers Lessons for Costly California

-

The SlickNovember 24, 2025

The SlickNovember 24, 2025California Endures Whipsaw Climate Extremes as Federal Support Withers

-

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025This L.A. Museum Is Standing Up to Trump’s Whitewashing, Vowing to ‘Scrub Nothing’

-

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025Is the Solution to Hunger All Around Us in Fertile California?