Latest News

A Jared Kushner-Connected Company Is Buying an L.A. Mall

Why wasn’t an African American community group allowed to make a final bid on the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza?

“Forty acres and a mall!”

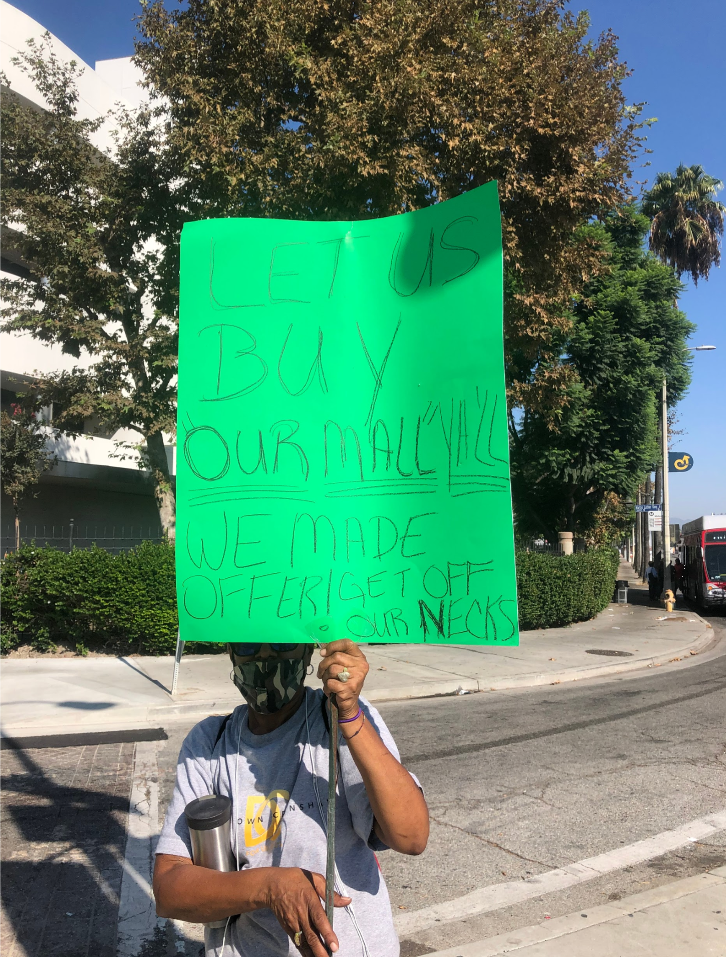

“Let us buy our mall, y’all!”

On a hot September morning in Los Angeles, volunteers from Downtown Crenshaw Rising chanted and marched in front of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, drawing curious looks from passersby. The Black community group has been seeking to acquire the mall for community ownership, and to build more than 800 units of affordable housing while discounting retail spaces for local businesses. This August, the group financed a $100 million bid for the property; it was rejected by the bank handling the sale.

Co-published by L.A. Taco

Veronica Sance, a resident of the neighborhood since 1972, won over an MTA bus driver as he paused for a red light. “We made an offer!” she yelled through the glass door of the bus. “Sign the petition!” The driver, who was African American, nodded repeatedly, made a thumb-up and pulled the bus into traffic.

The Downtown Crenshaw Rising plan for the Plaza would include office space, a community-owned hotel and affordable housing units.

Built in 1947, the mall site was originally just the Broadway and May Company department stores, along with a collection of other shops, until the 43-acre plaza was constructed in 1988. Then-mayor Tom Bradley hailed the project as the first major enclosed mall in a Black neighborhood, and Tupac featured the plaza in his 1996 video “To Live and Die in L.A.,” rapping in front of the See’s Candies store, surrounded by family and friends. But the property has fallen on hard times; Walmart and Sears both left in recent years, together vacating a third of the retail space. In 2018, the current owners decided to sell the property.

Baldwin Hills resident Veronica Sance. (Photo: Jack Ross)

In addition to building housing in the mall, Downtown Crenshaw hopes to purchase adjacent buildings with a “community stabilization fund,” removing units from the real estate market and converting them to affordable housing. A six-acre park would provide a venue for concerts, exhibits and performances. Plans also include office space and a community-owned hotel, whose workers would be represented by the hospitality union Unite Here Local 11, according to Downtown Crenshaw board member Damien Goodmon. (Disclosure: The union is a financial supporter of this website.)

Perhaps most meaningfully, under the Downtown Crenshaw plan, community members could buy shares of the mall itself. Their acquisition would mean Black ownership of an iconic African American commercial center, in a city still scarred by the redlining policies that primed communities of color for gentrification.

Los Angeles is now the most expensive housing market in the country; an average apartment rents for $2,524 a month. Black Angelenos make up 8% of the local population, but are 34% of the unhoused population — a number likely to grow alongside rising rents — and by 2019 estimates, the city is short on affordable housing by more than half a million homes. In the 21st-century war for Los Angeles, a bitter fight between corporate real estate and the city’s desperate 99% has made a trip to the mall.

“There’s so few spaces that have that feel: that I’m in my own neighborhood and I’m in my space as an African American Angeleno. [Community ownership] would feel like a big win.”

~ Lynell George, author

Journalist and essayist Lynell George grew up near the plaza and says it was always a “hub.” She has been anxiously keeping tabs on the Downtown Crenshaw project.

“There’s so few spaces in Los Angeles that have that feel: that I’m in my own neighborhood and I’m in my space as an African American Angeleno,” says George. “[Community ownership] would feel like a big win.”

As real estate markets boom in Los Angeles, Goodmon worries his community is swapping disinvestment for gentrification.

“Nobody gave a damn about this neighborhood 20 years ago,” he said after the September protest, walking down Crenshaw Boulevard where businesses were shuttered and graffitied.

* * *

Capri Urban Investors (CUI), a private equity fund invested in by a number of public pensions, currently owns the mall. Los Angeles Fire and Police Pensions, the University of California Board of Regents and the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) are all current investors.

In 2019, the Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association, known as LACERA, transferred management of $318 million in property from Capri Capital Partners to DWS Group, a Deutsche Bank subsidiary. Now, LACERA supervises Capri Urban Investors as part of a powerful “advisory committee.” In 2007 SEC documents, CUI named LACERA, NYCERS, New Jersey’s Common Pension Fund E and the UC Regents as its “beneficial owners.”

Capri invests such pensions in real estate to maintain and grow assets, then uses the public money as capital for private development, a controversial phenomenon that can see workers displaced by their own retirement plans.

“It’s the same argument I heard [from corporations] back in the 1970s and ’80s with the end of the apartheid movement. They washed their hands of any social responsibility.”

~ Baba Akili, Black Lives Matter organizer

Downtown Crenshaw Rising volunteers have been attending LACERA board meetings since May, demanding the pension investors intervene in the sale. LACERA says it has no control over proceedings because Deutsche Bank’s subsidiary is overseeing the sale as an independent fiduciary. LACERA and the rest of the advisory committee appointed Deutsche Bank to that role, however.

“We have 19 comments regarding the downtown Crenshaw mall,” a LACERA timekeeper announced at its September 30 meeting. Board members Wayne Moore, Herman Santos, Vivian Gray and Gina Sanchez turned off their Zoom cameras.

“You’re simply denying our bid to buy what we already own with our own pension dollars,” Downtown Crenshaw organizer Jan Williams told those who remained. The departed board members returned after the conclusion of public comments.

Black Lives Matter organizer Baba Akili rejects LACERA’s claims that it cannot control the sale.

“It’s the same argument I heard [from corporations] back in the 1970s and ’80s with the end of the apartheid movement,” he says. “They all kind of washed their hands of any social responsibility.”

CIM backed out of the mall sale when Downtown Crenshaw Rising attacked it for partnering with Jared Kushner on a number of developments.

The mall has underperformed for Capri: In April of 2020, Deutsche Bank accepted a $100 million bid for the property from L.A.-based CIM Group, roughly $30 million less than Capri paid in 2006.

But Downtown Crenshaw attacked CIM for partnering with President Trump’s son in law, Jared Kushner, on several developments, including Brooklyn’s controversial Watchtower property, and for its acquisition of the Trump SoHo hotel. In June of 2020, CIM backed out of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza sale. CIM’s exit was best for the community, the company announced on Instagram.

* * *

Over the summer, Downtown Crenshaw financed and prepared an offer. SmithGroup, the architects behind the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, signed on to design the expansion.

In August, Downtown Crenshaw submitted a $100 million initial bid. Real estate behemoth Jones Lang LaSalle backed the offer, as did 10 “sustainable” — or “ESG” — investors, who seek lower returns in exchange for beneficial societal impact, though Goodmon wouldn’t disclose who the investors are. Downtown Crenshaw also told the Deutsche Bank subsidiary that the group could add 5% to competing offers in subsequent rounds.

Negotiations advanced to the second round but Downtown Crenshaw were refused the chance to submit a best and final offer, leaving the group outraged. Goodmon says this is highly irregular.

Spencer Couts, an assistant professor of real estate development at the University of Southern California, however, says the rejection is not so strange. “You will regularly see bidders who are in the early rounds of the bidding process that don’t make it to subsequent rounds or the final round,” he wrote in an email, adding that he didn’t know the specifics of the Crenshaw Plaza deal.

In October, Deutsche Bank selected LIVWRK and DFH Partners to acquire the mall instead for a price believed to be about $110 million (though the sale is not yet finalized), a decision based on “all the components of the submissions, including community engagement and sufficient proof of financing,” according to a bank spokesperson. If the sale is confirmed, Goodmon says, “we along with other stakeholders are looking at several legal maneuvers that would wrap this thing up for a while.”

The plaza’s new buyers have worked with Kushner, too. In fact, LIVWRK was the third partner in the Watchtower sale, with Kushner and the mall’s first buyer, CIM Group. (Kushner Companies sold its stakes in the property in 2018.) LIVWRK CEO Asher Abehsera is even known as “the idea man behind Jared Kushner’s Dumbo Heights,” the Brooklyn mega-development containing the Watchtower property.

At a recent neighborhood council meeting, Abehsera told a Zoom audience that community “passion” first drew him to the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza. In Brooklyn, he learned that rising tides really did raise all boats, he said.

The “Grandmamas Gang.” (Photo courtesy of Downtown Crenshaw Rising)

Baba Akili, also in attendance, addressed the CEO and did not mince his words.

“We want to say, from Black Lives Matter L.A. — before you come to this community, before you even step foot here, you will be challenged, you will be confronted, you will be dealt with,” he told the LIVWRK founder. “You are not welcome here in Los Angeles.”

On Thursday night, a crowd of about 40 demonstrators from Downtown Crenshaw and Black Lives Matter L.A. gathered outside Abehsera’s house in Beverlywood. Akili reiterated his warning to the CEO:

“To the neighbors, if he continues to do this, expect to see us again,” Akili said into a bullhorn. “Just ask Jackie Lacey!” — a reference to Los Angeles’ recently defeated district attorney, who had long been a Black Lives Matter target.

The crowd roared.

Abehsera did not answer repeated requests for comment for this story.

* * *

Veronica Sance lost her job last spring and feared her housing would follow. Though her fortunes have since improved, she wonders how she will survive if luxury development at the plaza increases rents even more.

“Where am I gonna go?” she says. “I’m not going under the freeway.”

Sance still has the sewing scissors her mother bought for her at the mall’s Broadway store when she was a girl. On the morning of October 27, she was one member of the “Grandmamas Gang” who rang L.A. City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson’s doorbell, asking him to oppose the sale.

County Supervisor-elect Holly Mitchell has stated her support for the Downtown Crenshaw bid; her defeated opponent, Herb Wesson, and Councilmember-elect Mark Ridley-Thomas also tweeted their support for community ownership but did not directly endorse an acquisition by Downtown Crenshaw Rising.

Harris-Dawson didn’t answer his door, though the Grandmamas saw his car in the driveway. He declined to comment for this article.

Sance says Harris-Dawson should respect his elders and respond to their request for dialogue.

Jan Williams, a Black Lives Matter and Downtown Crenshaw activist, lives near the mall in a house her grandfather purchased in 1959.

“I’m raising a son in this neighborhood, and I expect one of these days I’ll have grandkids,” she says. “I want them to be able to live and thrive in this neighborhood as well.”

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

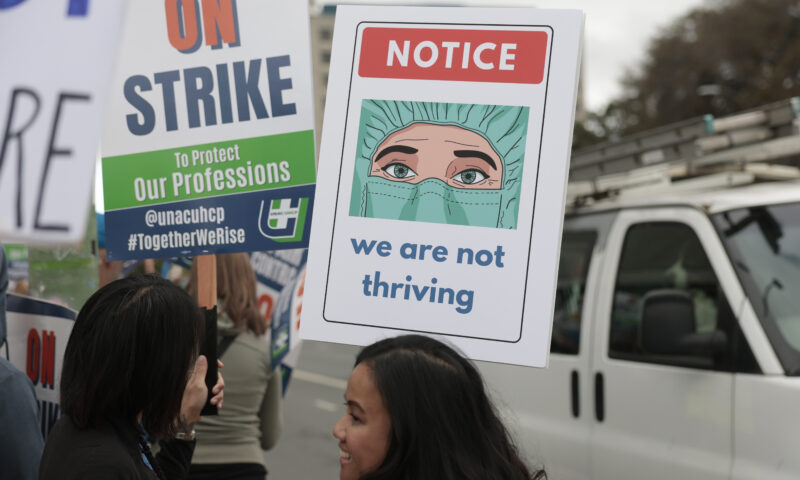

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?