Politics & Government

Is Recalling Gov. Newsom the Only Way Republicans Can Win California?

The GOP seeks to spark an improbable conservative comeback in a true-blue state in the Sept. 14 vote.

The fall of the Republican Party in California didn’t come without warning.

Republican guru Stuart Spencer, a key strategist for Ronald Reagan’s successful races for governor and then president, noted back in 1997 that the state’s demographics were evolving, and the party needed to adjust. The anti-immigrant rhetoric had to stop, he warned, or the party would likely sink into long-term decline.

Co-published by Sacramento News & Review

Spencer’s advice was ignored. Disgusted, he finally stepped outside of what’s become the party of Donald Trump last year, at 93 years of age, and voted for Joe Biden. It was his first vote for a Democratic presidential candidate since Harry Truman in 1948.

“Many in the Republican Party didn’t understand the dynamic of demography,” says Sherry Bebitch Jeffe, a longtime University of Southern California political scientist, noting the subsequent collapse of the state GOP. “Politics is demography over time, and demography was shifting toward voters that were friendly to the Democrats and, in particular, Latinos.”

In California, a state long referred to as “Reagan Country,” Republicans no longer hold any statewide office — and there are few signs of a looming comeback.

The GOP is instead resorting to the only path to power left for a state party on life support: a recall election.

It worked once before, electing armchair Republican and action movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger to high office in 2003 while shoving aside the incumbent Democrat, Gov. Gray Davis.

The most serious GOP recall candidates were already planning to run in next year’s election, and two — businessman John Cox and former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer — have raised millions to fund their campaigns.

This fall, California voters will be tasked with deciding the fate of first-term Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom and, if he’s defeated, choosing from a still-developing roster of dozens of candidates to replace him. The recall vote is set for Sept. 14.

For Republicans, the recall offers a chance to not only unseat a powerful Democrat who leads a state of nearly 40 million and is a potential future presidential aspirant, but to get an early jump on the regularly scheduled gubernatorial election in 2022. The most serious GOP recall candidates were already planning to run in next year’s election, and two — businessman John Cox and former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer — have raised millions to fund their campaigns.

A recall election’s inherent chaos and a wide-open field of candidates wrestling for attention may not seem like an ideal path for Republicans to reassert sober leadership capable of winning back the governor’s office. But with lower voter turnout in an off-year vote expected to benefit the GOP, it’s an option they can’t ignore.

“I don’t get to make that decision because the recall’s qualified and it’s going to be on the ballot and I can either compete or not,” says candidate Doug Ose, a former Republican congressman and real estate developer from Sacramento. “I chose to compete.”

The recall was made possible largely through the efforts of statewide volunteers fueled not only by shared conservative leanings but also frustration with the state GOP. About 1.6 million signatures required to qualify for the special election were collected by grassroots activists unconnected to the GOP, says the leading recall group, the California Patriot Coalition – Recall Governor Gavin Newsom. Tellingly, the group claims, only about 450,000 were collected by paid signature-gatherers funded by the party.

“I’m disappointed in the Republican Party,” says recall campaign board member Mike Netter, a party member deeply frustrated by the state GOP’s inability to mount an effective counterbalance to Democrats in the state.

The Road to Recall

Leading the effort from Folsom is Orrin Heatlie, 52, a retired Yolo County sheriff’s sergeant, who adds, “My campaign’s relationship with the California Republican Party is contentious at best.”

In an interview with Capital & Main, Heatlie sounds motivated more by his support for the death penalty and other issues than by Newsom’s pandemic response, which drove the momentum for getting the recall on the ballot. The pandemic also inspired a judge to decide that signature gatherers should benefit from an additional 120 days for their effort, making it easier to get the recall before voters.

Heatlie understands that success in qualifying for the ballot does not mean that Republicans are resurgent. The GOP’s weakness is a sign the party has “lost the faith and confidence of their own base in California. There’s a reason people have walked away,” says Heatlie, a self-described “centrist conservative” who worked in law enforcement for 25 years.

One of many signs (and misspellings) attacking California Gov. Gavin Newsom as anti-shutdown protesters gathered at Los Angeles City Hall on May Day, 2020. Photo by Steve Appleford.

There has been, however, a well of passionate anti-Newsom sentiment in some corners of the state. At anti-shutdown demonstrations last year, Newsom was a frequent target of rage over the state’s pandemic business shutdowns, school closures and mask mandates. One protester in front of Los Angeles City Hall carried a sign that made Nazi comparisons — a drawing of the governor with arm outstretched and a misspelled slogan: “Hiel Newsom.”

But the governor himself gave his opponents a big boost when, in November 2020, he was photographed maskless for a lobbyist’s birthday dinner at the exclusive French Laundry restaurant in Napa Valley. Newsom admitted that attending the dinner at the Michelin-starred eatery was “a mistake,” and apologized to Californians. It was also the moment when a recall became inevitable.

“The number of signatures shot up on the chart,” Bebitch Jeffe says. “It fit the perception that people have of politicians being disingenuous, hypocritical, ‘Do as I say, not as I do.’”

The governor’s decision to dine at the French Laundry enabled the recall movement to trigger a substantial bill for Californians: The recall election is expected to cost state taxpayers more than $200 million to conduct.

Netter and Heatlie are promoting the recall as hosts of a call-in radio show in Los Angeles called “Friday Night at the French Laundry.” The recall campaign pays KABC-AM for the airtime.

“Newsom accelerated the curve of awareness in the state by acting like an idiot,” says Netter, 64, a former business executive who moved to California in the 1960s. “I’m new in politics, dude. And you always think that somebody else is going to be doing it, right? Somebody else is going to make the moves. The system will take care of it.”

In 2003, when then-Gov. Davis became the state’s first governor to ever be recalled from office, more than 100 candidates filed papers to enter a circuslike election driven by tabloid-friendly media coverage. Nontraditional candidates included Hustler publisher Larry Flynt, former “Diff’rent Strokes” child star-turned-reality television performer Gary Coleman, punk rocker Jack Grisham, porn actress Mary Carey, rising media figure Arianna Huffington and many others.

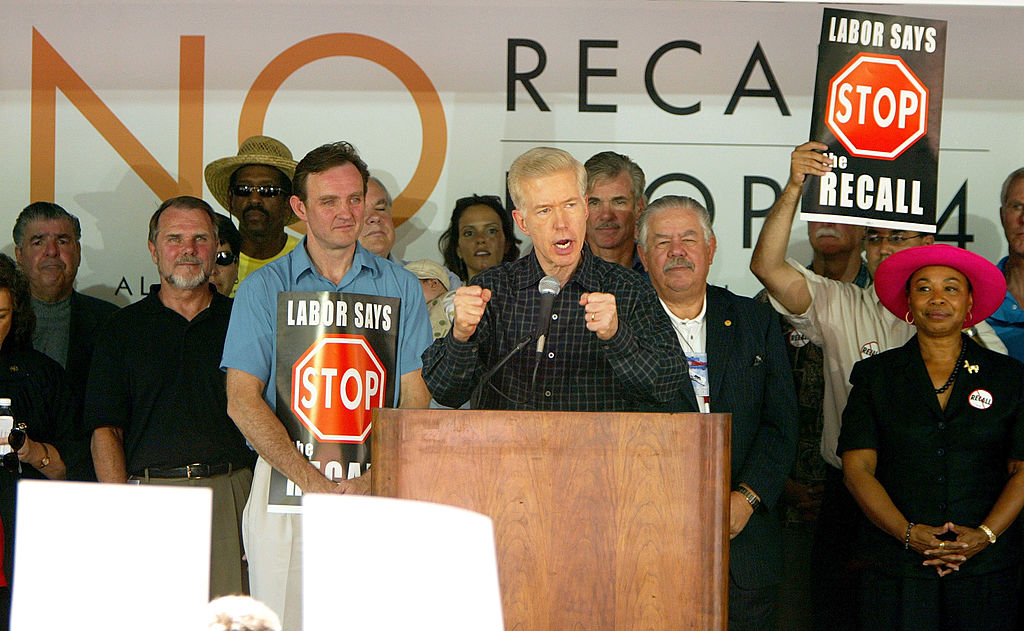

California Governor Gray Davis speaks at the Central Labor Council of Alameda County’s 46th annual Labor Day picnic September 1, 2003 in Pleasanton, California. Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

For political vets, it just looked like amateur hour — and a lot of noise with very little substance. They misread the moment, not to mention the unique appeal of Schwarzenegger, who was still one of the most beloved movie stars on Earth. Due to the nature of the recall, nearly all of the serious candidates were united in a singular goal: getting rid of Davis. In the election 55% of voters went against Davis, and he was removed from office.

“Davis never took the recall seriously, I think, until two weeks before the election and then went, ‘Oh my goodness, it’s real,’” recalls Bebitch Jeffe.

Newsom isn’t going to repeat that mistake, and his chances of survival are already much better than Davis’. A poll in May from the Public Policy Institute of California showed the governor with a comfortable margin of support, with 64% of state voters now backing his handling of the pandemic. So far, there is anemic backing for the Republicans vying to replace him. (Unlike with Davis, no major Democrat is expected to enter the race to potentially replace Newsom.)

“Everything that went wrong for Davis isn’t going wrong for Newsom,” Bebitch Jeffe adds. “He’s far ahead of where Davis was.”

When Republicans Won the Battle — and Lost a Generation

More than two decades ago, the historic turning point for the diminished fortunes for California Republicans was the arrival of Proposition 187, an anti-immigrant ballot measure that promised to deny undocumented workers access to schools and other essential public services. In his winning 1994 bid for reelection, Gov. Pete Wilson embraced the measure as an effective wedge issue against Democrat Kathleen Brown, but Prop. 187 would mark a turning point that caused many Latino voters to shift away from the GOP. (The measure was later declared unconstitutional in federal court and never enacted.)

To much of a Latino demographic that might otherwise have included many culturally conservative voters aligned with GOP positions on abortion and business, the Republican brand was deeply tarnished.

The number of California’s independent voters that lean conservative has grown since 2016 — an indication of how costly Trump has been to GOP party identification in the state.

Of the 20.9 million registered voters in California these days, there are nearly twice as many Democrats (now at 46%) as Republicans (24%), according to the Public Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

There are signs of very modest progress for Republicans. The GOP recently surpassed “no party-preference” in party registration in the state after several years when it was even less popular.

Part of the problem for the GOP is that even California’s independent voters lean Democratic, even if the number that lean conservative has also grown since 2016 — an indication of how costly Trump has been to GOP party identification in the state. Republicans in California didn’t leave their party to become Democrats; they largely just wanted to get away from Trump.

The ex-president is especially unpopular among voters under 25, a grouping that accounted for nearly two-thirds of new registrations. Not surprisingly, GOP candidates in the recall election are less likely to highlight their past support for Trump than they might in some other states.

“I understand people have heartburn with Trump,” says Ose, a 2016 state chairman for the combative president. “But I think with Trump, the good far outweighed the bad.”

Ose also recognizes the dismal position his party has found itself in the 15 years since he left office during the George W. Bush administration.

“Our messengers stopped talking about things that made a difference to the majority of people,” Ose says. “What they want to know is: Does the guy I’m voting for give a rip about whether I can pay my bills? Does that person care about whether I can get to work? What’s their view on public school?”

Can Republicans Bear Their Baggage?

John Cox lost to Newsom in 2018 in the worst showing by a gubernatorial candidate since 1950, falling nearly 3 million votes short of victory. In May, Cox launched his 2021 recall campaign with a statewide bus tour and brought along a rented 1,000-pound Kodiak bear. It was meant as a clever stunt to signify Cox’s newest chosen nickname: “The Beast.”

The 2021 recall circus had begun. The Republican businessman garnered plenty of valuable TV news coverage, but also ridicule for the spectacle. The San Diego Humane Society also investigated him for bringing a 7½-foot-tall wild animal into the city.

“I don’t think that the bear was very helpful,” suggests Bebitch Jeffe. “I joke that in the last public poll, Cox was at 6% and the bear was at 8.”

A 1,000 pound bear sits behind John Cox as he speaks during a campaign rally at Miller Regional Park on May 4 in Sacramento, California. Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

At least one other candidate — former Kardashian reality TV star and 1976 Olympic decathlon champion Caitlyn Jenner — had the ability to draw far more attention. Jenner launched what could be a groundbreaking moment for transgender rights, not to mention a disruption of the state’s traditional political lines, if not for the incoherent sloganeering of the candidate and a marked lack of policy substance.

Calling herself a “compassionate disrupter,” Jenner has national media coverage but few voters, with just 6% support, according to a poll released last month by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies.

The Jenner effort “doesn’t feel like a very serious campaign at all,” says Bob Shrum, a veteran senior consultant for several national and local Democratic campaigns. The former Olympian and Kardashian family figure has so far largely emphasized the celebrity circuit of TV talk shows over the hard work of retail politics at ground level.

Jenner has been rewarded with publicity but little traction. In this election at least, voters currently seem uninterested in candidates without serious proposals, but traditional Republicans likely face a dead end in statewide elections if they are “anti-choice, anti-LGBTQ, and pro-Trump,” insists Shrum.

Republicans’ Punk Rock Revolutionary

The roots of California’s peculiar recall election law go back 100 years, but it wasn’t until 1994 that it was transformed into a real weapon by a young Republican activist and sometime prankster named Jimmy Camp. And his first target was another Republican.

With an acoustic guitar and arms covered in tattoos, Camp spent many nights onstage playing punk rock and outlaw country, and days working as an operative in the Orange County GOP.

That year, state conservatives were upset with moderate Republican Assembly member Paul Horcher, who blocked his party from taking control of the state Assembly when he declared himself an independent and voted to retain liberal Democrat Willie Brown as speaker.

Camp launched a recall effort, and Horcher was out of office within a year. It was the first successful recall in the state in four generations.

Eight years later, Camp was deeply involved in the recall of Davis. During that campaign, Camp worked for a pro-Schwarzenegger PAC as a ground level operative whose job was to depress turnout of the progressive Democratic base. He did this by loudly underlining the governor’s center-right positions on the environment, immigration and LGBTQ issues.

Outside Davis’ public events, Camp would shout: “He’s not one of us!”

During the 2003 recall drive, voters still had memories of recent Republican governors, so the party’s growing electoral instability in the state wasn’t obvious.

Camp was photographed with Rep. Maxine Waters at a gathering of Latino activists protesting Davis for not supporting driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants. At another, he showed up at an environmental gathering at the Santa Monica Pier, where the governor was appearing with Pierce Brosnan fresh off his last James Bond film.

“I had this megaphone and I’d organized all these protesters,” says Camp, who remembers Davis was “cool as a cucumber. But, man, I thought Pierce Brosnan was going to punch me in the face. I walked with them with a megaphone, like a full-on hippie yelling at them three feet from his face: ‘You’re a toxic polluter!’ It was actually pretty funny.”

During that recall drive, voters still had memories of recent Republican governors, so the party’s growing electoral instability in the state wasn’t obvious — and Schwarzenegger broke from numerous traditional GOP talking points. His moderate positions on social issues found an audience, and being married to a Kennedy (TV journalist Maria Shriver) didn’t hurt his image.

“He wasn’t like your typical Republican,” Camp adds. “He supported a woman’s right to choose. He supported rational gun control. He passed that smell test for the more blue dog-type Democrats and independents.”

Schwarzenegger experienced some wild ups and downs during his two terms in office, and one final, hugely embarrassing scandal in his personal life just after he left office: revelations about an affair with his housekeeper, who it was revealed bore him a son.

But the former governor has since regained much of his mainstream popularity in the state, in part for his open criticism of Trump.

If Schwarzenegger represents the kind of moderate that could win votes for Republicans, the base of his party has mostly rejected him as a model.

Ose says, “A schism developed between the bulk of the Republican electorate here in California and Gov. Schwarzenegger. I think those last few years, he kind of got away from being representative of the Republican Party.”

Ose prefers to look back to Republican Gov. George Deukmejian, a law-and-order former state attorney general who led the statehouse for two terms during the Reagan era. That was a time when mainstream conservatives had firm control of the state GOP.

There is also the issue of the national Republican Party being out of sync with most California voters. The last time a Republican presidential candidate won the Golden State was the victory of George H.W. Bush in 1988.

The state still has a hugely important federal office holder in Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the House minority leader, who’s expected to become speaker if the GOP recaptures the chamber in the 2022 midterms. But it is very difficult to imagine McCarthy, even with his influence, winning a statewide race, especially given his public alignment with Trump.

A Recall Regret

Camp worked in the Schwarzenegger administration, and he continues to work as a political consultant. He quit the GOP with the rise of Trump and became a volunteer for the Lincoln Project, the ongoing national campaign against Trumpism led by disaffected Republicans.

“Honestly, looking back on the Gray Davis recall, I don’t believe he deserved to be recalled,” Camp admits now. “There wasn’t malfeasance in office.”

California once swung frequently between the two major parties, but now it is effectively a one-party state, making it impossible for the GOP to simply peel off a few unhappy supporters and win back Sacramento. The 2019 election of GOP state party chair Jessica Millan Patterson, 39, was part of a rebuilding effort. She is the first woman and the first Latina in the role.

But she still has to work in the shadow of Donald Trump, the twice impeached, anti-immigrant billionaire force of personality who upended the national GOP via tweets in ways that made reclaiming California more difficult. Trump’s efforts to retain control of the Republican Party since leaving office continue to aggravate the situation in the Golden State, which he lost by 5 million votes.

“In a normal world, [Patterson] could really have turned it around, but because of Trump, she’s just not going to be able to do much,” Camp says.

“There are no bright spots for Republicans,” he says. “I don’t see them ever becoming relevant again in California.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care