Society

Is Los Angeles’ Homeless Epidemic Spurring Business Vigilantism?

After an Eagle Rock homeless encampment was dismantled, one business allegedly went a step further by covering the sidewalk with what an employee described as a mix of “half lime and half marking lime.”

“They took all my shit,” a homeless man said. “I feel like the government wants us dead.”

Los Angeles’ inability to arrest a dramatic rise in the number of people sleeping on the city’s streets has allegedly spurred one Eagle Rock lumberyard to coat a public sidewalk with a substance that can burn skin, in an apparent effort to discourage the creation of another homeless encampment in this middle-class community.

When the city on January 30 cleared such an encampment from the sidewalk outside Eagle Rock Lumber & Hardware — part of a clean-up effort occurring across Southern California amid the worst Hepatitis A outbreak since a vaccine was released over three decades ago — the business went a step further: It covered that sidewalk with what one employee described as a mix of “half lime and half marking lime.”

Lime is not to be touched, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which recommends wearing goggles and protective clothing when handling. Contact can result in eye and skin burns, as well as cause the forming of cysts, while inhalation can harm the upper respiratory system.

Marking lime, by contrast, is used on athletic fields and is safe to touch.

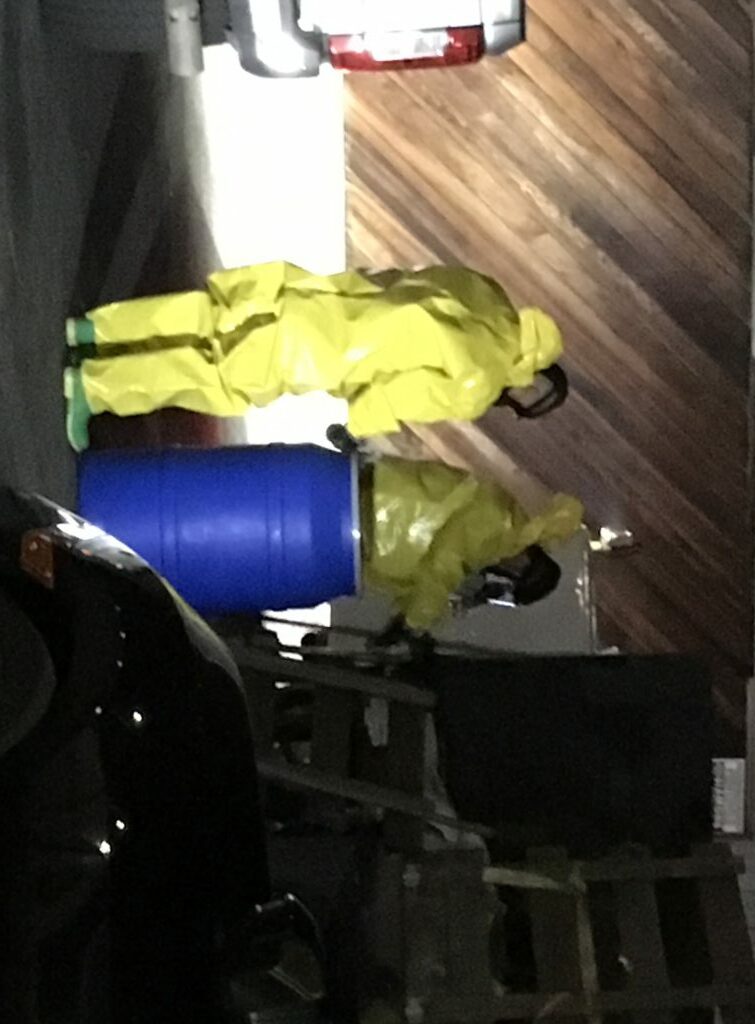

L.A. County Fire Dept. Hazmat vehicle at clean-up scene.

L.A. County Fire Dept. Hazmat vehicle at clean-up scene.

The employee, who declined to give his name, citing potential retribution from homeless advocates, claimed the intent was to disinfect and deodorize. The city’s sanitation crew may have removed the encampment outside the business, but it did not leave the area clean. “It smelled like piss and all kinds of stuff,” the man said. Indeed, the day after the sweep feces could still be seen on the sidewalk, alongside a hypodermic needle. “Our customers are complaining.”

But two eyewitnesses maintain that the same employee told them something else, and they suggest a different intention.

Michael Steinborn of Atwater Village was at the lumberyard the morning of January 30, monitoring the city’s cleanup as part of a rapid response team formed by the Democratic Socialists of America, Los Angeles, to document the dismantling of homeless encampments. He said the employee told him that he “put lye out,” pointing to a stoop on the property, and that he was “gonna pour more all around.”

“It was like he was putting blood meal out for rabbits in a garden,” Steinborn said, referring to a substance used to discourage pests.

Lye can cause skin and eye burns, as well as temporary hair loss, according to the CDC. (Capital & Main is not aware of any test results that show the actual composition of the substance.)

Two views of the affected sidewalk. (Sidewalkher

Two views of the affected sidewalk. (Sidewalkher

photos by Charles Davis)

Jenna Steckel, another DSA member, said she too heard the employee promise to spread “lye.” According to Steckel, the man also “told us he had already poured lye on his steps, which he showed us, and there’s nothing particularly dirty about those steps.” That, she argued, suggests the business simply did not want people sleeping there.

Ryan Kelly, an Eagle Rock resident and DSA member, said he arrived at the scene later that afternoon and a white substance had indeed been spread over the sidewalk. “I saw a young woman [walk] through it in flip flops,” he said. “I saw someone walk their dog through it.”

Nearly 58,000 people are homeless in Los Angeles County, according to the official 2017 count — a 23 percent jump from the year before, witnessed in the spread of encampments far from the concentrated poverty of Skid Row, the region’s traditional home for the shelterless.

The spread has corresponded with what the California Department of Public Health calls “the largest person-to-person… hepatitis A outbreak in the United States” since 1996, when the vaccine was released. Most of those affected by the virus, spread by contaminated feces, are homeless; 21 people have died.

While L.A. County voters last year approved $1.2 billion in spending on housing for the homeless, and millions of dollars more in services to keep them housed, local authorities have also stepped up their dismantling of homeless encampments. Between January 2015 and July 2017, the city of Los Angeles had swept up 16,500 encampments at a cost of $14 million, the Los Angeles Times reported.

The city also removed over 3,000 tons of trash in that time — before the Hepatitis A outbreak began — and a September 2017 report from the Los Angeles City Controller recommended that efforts to dismantle encampments be increased. But many of those living on the streets say that this trash is their stuff, spurring groups such as DSA to document the cleanings, announced by the city 72 hours in advance, to help that ensure clean-up crews abide by the law.

That mission also now extends to ensuring local businesses abide by it too.

Kelly, part of DSA’s rapid response team, said he called the Los Angeles Fire Department to report the dumping of what he believed to be lye, after consulting with those who had been evicted from the sidewalk in front of the lumberyard. LAFD spokesman Brian Humphrey confirmed that a crew was sent out that evening in response to the call. “They spent 22 minutes at the scene,” he said. “It’s not clear what action they took.”

According to Kelly, the fire crew was rather hostile. One fireman “gave us a big speech about how business owners were tired of homeless people defecating and urinating everywhere,” he said. But that fireman also said he would tape off the area and tell the business owner to clean up the sidewalk, an account supported by Steinborn and another member of DSA, Shelby Li.

The substance was still there on the evening of Wednesday, January 31 — with the addition of two orange traffic cones. Those now living across the street were afraid to go anywhere near their former campsite.

“That’s poison,” said Michael Anthony, standing outside of a tent. “That shit will eat your body. Obviously it’s dangerous because they put cones [out].”

But he was more upset with the city than the business. “They took all my shit,” Anthony said. “I feel like they don’t care about us. I feel like the government wants us dead.”

Lye or lime, the government, in the form of a Los Angeles County Fire Department Hazmat team, did come back. Just after midnight on Friday, February 2, spokesperson Randall Wright said, a team was dispatched to “lend some expertise” to the Los Angeles Police Department. He referred all further questions to the LAPD.

The LAPD did not return calls requesting comment by February 5, but last week confirmed receiving reports about the dumping of white powder at the site.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care

-

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026Agents In ICE Shootings Made Racist or Sexist Remarks, Records Show

-

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026As Climate Crisis Upended Homeowners Insurance, the Industry Resisted Regulation