Latest News

Hillside Villa Tenants Face Eviction While L.A. Tries to Buy Their Property

As the city’s eviction moratorium expires, Los Angeles ponders action to keep longtime Chinatown residents in their home.

Last May, more than 20 Los Angeles tenants celebrated wildly in City Hall: the City Council had just voted to try to buy their 124-unit building from their landlord, potentially saving them from rent increases of as much as 300%.

The council authorized the Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD) to appraise the Hillside Villa building in Chinatown and then make an offer to purchase it. But more than six months later, no appraisal has been conducted and no offer has been made. The tenants who celebrated in May could find themselves facing eviction after pandemic eviction protections expire at the end of the month.

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

“I don’t think anyone can pay the increase,” Eva Maria Arias says through an interpreter. The 82-year-old had her rent jump from $1,150 to $2,500 when the affordability covenant expired. “There are elderly people here. There are people on Social Security.”

Hillside Villa was built in 1988 using government tax credits in exchange for the owner keeping rents affordable for 30 years, an agreement called an affordability covenant. After the covenant expired in 2018, landlord Tom Botz issued tenants 200% and 300% rent increases. A May 9 LAHD report said at least 85% of the building’s current tenants said they made less than 80% of the Area Median Income, which is around $85,000 for a household of three.

In Los Angeles, 3,700 more units were expected to lose their affordability covenants between 2021 and 2023, according to LAHD; more than 10,000 in L.A. County could lose their covenants by 2031, the most by far of any county in the state, according to the California Housing Partnership.

The Hillside Villa Tenant Association formed in 2019 to fight the increases, pressuring the tenants’ councilmember, Gil Cedillo, to intervene by protesting outside his home and business meetings. Cedillo negotiated a 10-year extension of the covenant that July, but the deal collapsed (Cedillo says Botz walked away from the deal, while Botz says they never had one). The Hillside Villa Tenant Association then demanded the city seize the property with eminent domain — a process through which governments expropriate private property for a price determined by a judge — and transfer ownership to the tenants.

On May 27, 2022, the City Council unanimously voted to start a process to acquire the building, though the motion did not mention eminent domain. It only authorized the Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD) to appraise the property and submit a bid to the owner. Neither a majority of the City Council nor the mayor has indicated support for using eminent domain to purchase the building.

* * *

Still, tenants say the housing department wasted valuable time trying to get Botz to sell voluntarily as pandemic eviction protections grew closer to expiring. Botz has refused to let appraisers into the building, forcing the city to seek a court order to enter the property. The city moved to schedule that hearing after the tenants protested at the home of LAHD General Manager Ann Sewill. The hearing will happen on Jan. 30, two days before the Hillside Villa tenants will have to pay their increased rents or face eviction.

Monica Ruiz, a 23-year tenant in the property, had her rent increased from $1,000 to $3,225. If she’s evicted, she would have to move in with one of her grown children. “But they also live in very small apartments, and there are five of us in my apartment right now and a dog,” she says through an interpreter. “We would have to stay in their living room.”

Botz says he “never” had any intention of voluntarily selling the building, and he told the housing department as much “about a hundred times.”

“This is a unique asset,” Botz says. “It’s zoned for 345 units. We intend to take advantage of that and build a lot more housing there.”

He is incredulous when asked if he will begin the process to evict tenants in February.

“Are you asking me as a landlord if I would like tenants to pay rent?” he says. “If I would like them to live indefinitely in my building without paying rent? Let’s just say we’re hoping the city will come up with a good solution for them.”

If the city wins right of entry in court on Jan. 30, it will likely be another three months before the housing department returns to the City Council and the mayor with an assessment of available funding sources as well as what the building will cost to buy and renovate, LAHD’s Sewill said in an email.

“When these politicians don’t want to do something, they do endless studies on it,” says Hillside Villa organizer Jacob Woocher.

In May, attorneys for Botz said 71 tenants in the 124-unit building are on Section 8 — a federal housing program for low income tenants in which the government subsidizes the rent — and said he would accept Section 8 vouchers for the remaining tenants. But the tenant association rejects using Section 8 as a solution because it excludes undocumented tenants, locks tenants into their low income bracket — and keeps Botz as a landlord.

“We’re fighting for community control,” says organizer Annie Shaw.

* * *

With Botz refusing to sell, activists say achieving that goal likely depends on the city using eminent domain. The campaign to do so drew national coverage because acquisition of the building would be an important victory in the movement to decommodify housing: taking housing from private landlords — who are using it as a way to make money — and bringing it under tenants’ control and ownership.

The campaign also weaponizes local history. In the 20th century, the city used eminent domain to level homes in Chavez Ravine, the city’s original Chinatown and Bunker Hill, neighborhoods that surround the building. It replaced those poor, diverse communities with Dodger Stadium, Union Station and the museums and concert halls of Grand Avenue.

Eunisses Hernandez, the tenants’ City Council representative who defeated Gil Cedillo in June, said in a statement that she supports using eminent domain to buy the property “if necessary and feasible.” On Halloween, then-mayoral candidate Karen Bass told tenants she looked forward to working together and that “I like the idea [of eminent domain,] but it takes a lot of time.”

Organizer Jacob Woocher says elected officials who accept donations from developers are threatened by the effort, which would set a precedent for “expropriating private property for low income housing.”

Section 8 tenant Catherine Sanford calls Botz a “slumlord.” Though she lives off government disability payments, he charges her and other tenants $100 for parking each month while she and her daughter “struggle to pay” their $1,200 rent.

Botz’s management team has also attempted to prohibit children from playing in the central courtyard — it was long a community space for families, according to Leslie Hernandez, who grew up in the building — and removed seesaws and barbecues from the space. This summer, Botz hired a landscaping crew to uproot the community garden maintained by elders in the building like Eva Maria Arias, 82, who organized a blockade at the building entrance and prevented the landscape crew from entering.

Monica Ruiz and her now-deceased mother first planted chilis, guavas, avocados, papayas and herbs in the courtyard’s dirt 20 years ago.

“We want to be owners,” she says. “We could plant whatever plants and trees we want.”

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main.

This story has been edited since its initial publication to correctly identify Catherine Sanford.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

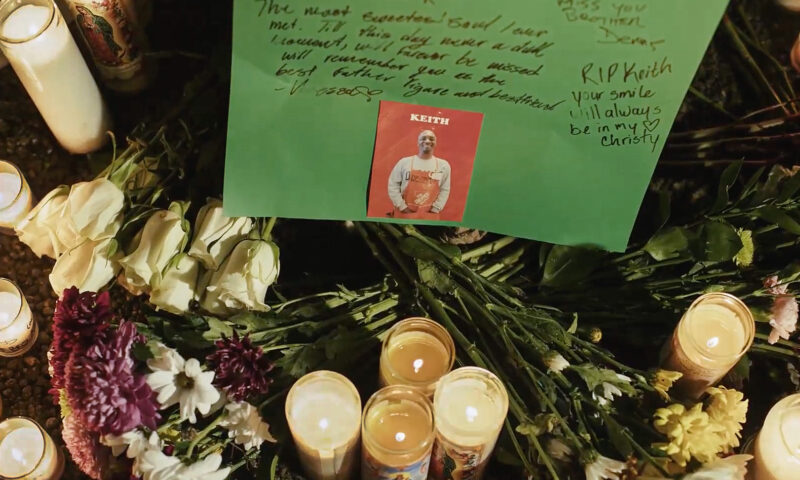

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026Keeping People With Their Pets Can Help L.A.’s Housing Crisis — and Mental Health

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026When Insurance Says No, Children Pay the Price