Latest News

Courthouse Interpreters Say They Lack COVID Protections at Work

Translators claim working within whisper distance of defendants makes them especially vulnerable to the coronavirus.

Just before Christmas, Silvia Vico learned that she may have been exposed to COVID-19 at Downtown Los Angeles’ Criminal Justice Center (CJC), where she works as an interpreter. Vico had to learn this through a colleague — and almost by accident. “I was told the courtroom where I worked the previous week was locked, with no explanation,” Vico said. With a little digging, she learned that the court reporter in that courtroom had tested positive.

Co-published by Patch

“[The administration] sent everyone else who worked in that courtroom home, but nobody told me, because the [infected] reporter didn’t mention me.” Vico later tested positive, and was forced to do her own contact tracing: She told 16 co-workers who had been in contact with her recently that they may have been exposed, even though they had been following protocols and wearing masks. But when they asked to quarantine, they all received pushback from supervisors and from human resources.

“Since [Sergio Cafaro’s death] I can’t get out of bed. Who is next? It’s like a death trap”

— Ariel Torrone, courthouse interpreter

One longtime coworker, Sergio Cafaro, was refused paid time off to quarantine and he didn’t question it for fear of losing his job, according to another interpreter and close friend of Cafaro’s, Ariel Torrone.

“He was bullied to come in,” Torrone said. Cafaro, who then tested positive, went into the hospital on Dec. 30. Two weeks later, Cafaro died.

“I love my job, and I always enjoyed coming to court,” Torrone said. “Since [Cafaro’s death] I can’t get out of bed. Who is next? It’s like a death trap. In a way it’s worse than [working in] a hospital. At least they have PPE [personal protective equipment].”

Ann Donlan, a spokesperson for the Superior Court of Los Angeles County, denied that court staff or management bullied Cafaro, and added that, based on court documents and contact tracing interviews conducted during Cafaro’s incident assessment, “quarantine for Mr. Cafaro was not warranted because he did not meet the definition of close contact under CDC and Los Angeles Department of Public Health (LADPH) guidelines.”

Donlan said that since Jan. 1, courts have been following the state workplace COVID safety standards of Assembly Bill 685, which require employers to send daily notices to employees of COVID-19 cases within the workplace.

Interpreters interviewed for this story said they feel unsafe at work and that management wasn’t taking their concerns seriously. They spoke of crowded hallways, packed elevators,

cavalier cops and inattentive bailiffs.

“Consistent with CDC and L.A. County Department of Public Health (LADPH) guidelines, the Court always has notified the identified close contacts, including justice partners and attorneys, of those individuals who have tested positive for or been diagnosed with COVID-19. Presently, the Court’s daily notice to employees and judicial officers provides all positive COVID-19 cases throughout the county court system, much beyond the statutory requirements.”

Donlan added, in a separate email, that “following the law should never be construed as intentionally concealing information. Likewise, even when an employee is identified as a close contact, the Court does not reveal the name of the COVID-positive individual to an identified close contact.”

Capital & Main interviewed interpreters working in the L.A. County Superior Court system, on the record and off. They claim the nature of their work makes them especially vulnerable to COVID; for one thing, interpreters must work in close proximity to defendants, sometimes mere inches away, in order to whisper their interpretation of everything happening in the courtroom. All said they felt unsafe at work and that management wasn’t taking their concerns seriously. They spoke of crowded hallways, packed elevators, cavalier cops, inattentive bailiffs and zero enforcement of mask-wearing throughout the buildings.

One interpreter at CJC, who requested to not be named, described in an email an especially risky procedure, interpreting for a defendant in “lock-up,” an enclosed, non-ventilated room or cell, usually adjacent to a courtroom.

Interpreters, unlike court reporters or bailiffs or judges, “float” between courtrooms — sometimes up to six different courtrooms a day — and don’t have their own offices.

“The doors are locked, and the only person who has the key is the bailiff,” the interpreter wrote to Capital & Main. “Once we’re in there, we’re stuck until the bailiff comes to let us out. I can’t just run out, for any reason, ever. I always refuse to go into lock-up, now in pandemic times, but I think most colleagues do go in there.”

In addition to accusing management of declining paid time to quarantine, interpreters allege that time off is granted arbitrarily, and that there should be more remote-work positions for interpreters. (There are only two telework positions for all interpreters at CJC.)

The highly mobile nature of their job, they say, puts them in greater danger than other court employees. Interpreters, who, unlike court reporters or bailiffs or judges, “float” between courtrooms — sometimes up to six different courtrooms a day — are in contact with many more people, and don’t have their own offices. Instead, they’re packed into waiting rooms.

* * *

The 19-floor CJC is one of the largest criminal courthouses in the world, with about 60 courtrooms. But it’s not the only building with COVID-19 outbreaks. To keep foot traffic down, criminal courts in Los Angeles County, as with many courts around the nation, have been closed for trials since March. But other proceedings that don’t require juries, like preliminary hearings and probation progress reports, have been going on since July.

“They do not screen people entering [the] courthouse,” said Uri Yaval, an interpreter at CJC. “I was exposed by a one-half-hour interview [with a defendant]. Halfway into the interview he said he was just released from the hospital and still had symptoms of COVID.” Yaval was allowed to go into quarantine.

Responding to allegations that there are no screenings at courthouse entrances, Donlan said that temperature screenings are not an effective measure to screen for infected individuals. Instead, she said, court employees and judicial officers are required to check themselves for symptoms daily, and if they fail the check, they should not report to the courthouse.

Still, people infected with COVID-19 can spread the virus for days before exhibiting symptoms.

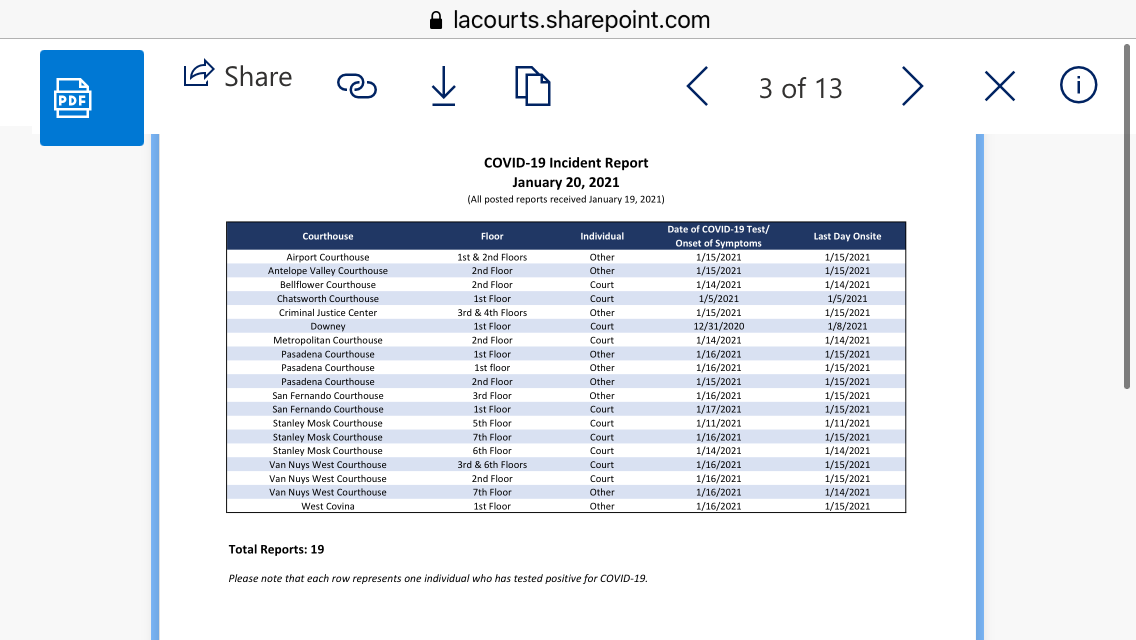

Interpreters speaking with Capital & Main said they understand that, legally, the court cannot disclose the names of people who were infected or symptomatic, but that practice, they say, makes it impossible to know exactly how close or for how long they may have been in contact with someone who is sick. What interpreters and other court employees receive is a daily email alert of outbreaks per court, showing the date a person first had COVID-19 symptoms, and the last day they worked on-site.

A daily notice of outbreaks at L.A. County courthouses on Jan. 20 showed that most people left the workplace on the day they experienced symptoms of COVID-19. In one case, however, an employee at the Downey courthouse apparently kept working on-site for a week after testing positive. (Click on screenshot below.)

* * *

Theoretically interpreters could perform their tasks remotely from a safe distance, but that would require judges, lawyers and prosecutors to wait for the translator to give their interpretation, nearly doubling the time it takes for a proceeding. “[Court administration is] more concerned with efficiency, moving cases along, than our safety,” Vico said. “When you say you may have been infected, they accuse you of not following protocol.” Interpreters insist they do follow safety protocol, but it’s the other people in the courtrooms and public spaces who sometimes do not.

And not everyone working at the courthouses is an employee of L.A. County Courts; bailiffs, for example, work for the sheriff’s department, which has its own safety protocols.

The rate of new COVID-19 infections in Los Angeles County has begun to slow, but at its peak in mid-January, there were more than 40,000 new cases daily. As of Jan. 28 there were more than a million total known infections in the county, and more than 16,000 deaths. Rates of COVID-19 have soared among the inmate population in L.A. County jails, but accurate figures are hard to come by because defendants are tested when they enter the system, but not routinely while they’re incarcerated.

Donlan affirmed that the L.A. Superior Court has updated its safety measures since Jan. 1, and that it allows employees who test positive, as well as those who exhibit COVID-19 symptoms, to quarantine with pay. Those deemed not to be in close contact with an infected person may also quarantine, but there is no guarantee of paid time off.

Interpreters told Capital & Main that this may be what the court system is doing on paper, but not in practice, and that the court and interpreters have different definitions of “close” contact.

Roxana Cardenas, a steward for the California Federation of Interpreters Local 39000, stated in an email that the union is pushing for more telework positions for interpreters, as well as size limits at all spaces — and enforcement of the limits — and more and better PPE.

Cardenas also claimed that many judges don’t like using technology and have avoided using video remote platforms because it slows down the process. “And most of the courthouses [built before] the mid-’90s don’t have the infrastructure or high-speed wide band internet, anyway,” she wrote.

“Interpreters and translators are always an afterthought for policymakers.”

— Lorena Ortiz Schneider, American Translators Association

Another issue, Cardenas said, is bureaucratic red tape: “There are different levels of administration through which these decisions are taken; there are several departments (sheriff, probation, mediation, DAs, public defenders, etc.) who also must be on board, or even be willing to allow usage of space, equipment or internet nodes that are found within their bailiwick.”

“Interpreters and translators are always an afterthought for policymakers,” said Lorena Ortiz Schneider, a freelance interpreter in Santa Barbara and chair of the advocacy committee for the American Translators Association (ATA). “People don’t quite understand what we do, how we do it, or what is required for us to perform our work well and safely.”

According to the ATA, no COVID-19 deaths of court interpreters have been reported so far outside Los Angeles, though some interpreters have been infected throughout the U.S. The organization said that court proceedings in some states, such as Illinois, Texas and New Jersey, are primarily remote.

Nevertheless, court interpreters are included in the CDC’s rollout of COVID-19 vaccine priorities, and appear not by occupation, but as part of a broad category in vaccination phase 1c under “Other community- or government-based operations and essential functions.” Last month the ATA sent a letter to the new director of the CDC, Rochelle Walensky, urging her to revise its guidelines and include on-site court interpreters in phase 1b of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ vaccine recommendations. Unlike court interpreters, medical interpreters were put in phase 1a.

“We asked [the CDC] to consider court interpreters, because we are essential workers and mandated by the court,” Ortiz Schneider said.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit