California Expose

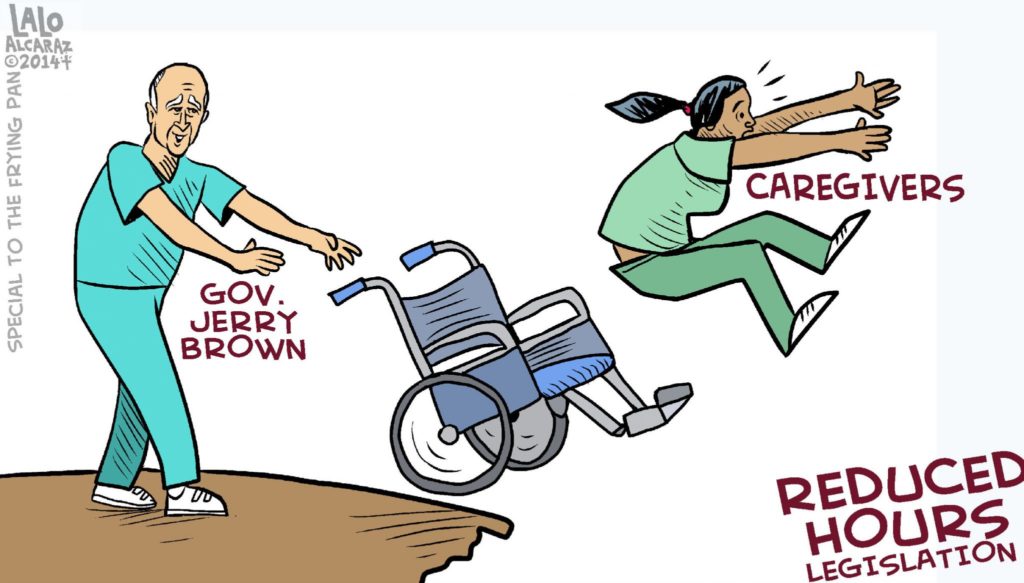

Careless: How Governor Brown Is Harming California’s Seniors and Disabled — and the People Who Care for Them

Andrea Vidales makes $9 an hour taking care of a blind Korean War veteran and an elderly couple in their Merced County homes. Under California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, she spends about 60 hours every week bathing her clients, preparing their meals, cleaning house, paying their bills, driving them to doctors and dealing with other aspects of their medical care. She was delighted, then, when the Obama administration, through the U.S. Department of Labor, announced new regulations last September requiring in-home caregivers to be paid overtime for working more than 40 hours a week.

Her good fortune didn’t last long. On January 9, Governor Jerry Brown unveiled his proposed $155-billion budget for 2014-2015 at a press conference in Sacramento. Under the governor’s budget, Vidales and hundreds of thousands of other home health care workers would be prohibited from working more than eight hours a day, or 40 hours a week. Now, suddenly, the state’s home health care workers are not only facing the possibility of not receiving overtime, but of also losing the extra hours they’ve been accustomed to working.

The overtime prohibition would cover all IHSS caregivers. The IHSS program, which has operated for nearly four decades, is designed to allow seniors and people with disabilities to live in their homes rather than in more expensive institutions – whose per-patient costs typically run five times as much as in-home care. Under the program, about 360,000 home health care workers provide care to roughly 450,000 people as part of California’s Medi-Cal program. It is five times larger than the next largest program operated by any other state.

Brown’s provision is intended to save California from paying the overtime required under the new federal regulations. But home health care workers say the overtime prohibition would have a devastating impact on their incomes, and advocates for seniors and the disabled claim that care would be disrupted for some of the state’s most vulnerable people. The ensuing conflict between federal generosity and the pressures of a state budget have set in motion a classic example of good intentions producing unintended consequences.

“It’s really going to create chaos for recipients and for present caregivers,” says Gary Passmore, vice president of the Sacramento-based advocacy group Congress of California Seniors. He warns that the elderly and disabled who require care beyond 40 hours a week will be forced to rely on other caregivers with less familiarity with their special needs. “Ironically, the people who need the most hours [have] the highest needs,” he says. “They are the frailest and the most profoundly disabled.”

The impact would be felt by a largely female workforce, whose members earn an average of $11.62 an hour. Vidales, for instance, would have more than 80 hours of pay cut each month and would lose more than a third of her current income.

“I would be really, really broke,” Vidales, a 62-year-old resident of the Central Valley town of Atwater, tells Capital & Main.

Under the program, elderly, disabled and blind recipients can chose the person who cares for them. In California, more than 72 percent of IHSS recipients receive care from a relative and more than 42 percent of caregivers live with the person for whom they provide care.

Mary Burch, a 72-year-old Modesto widow, is one such caregiver. She takes care of her severely disabled 40-year-old daughter, Christy. Under the IHSS program, Burch is currently paid $9.38 an hour for 272 hours a month. If the overtime ban goes into effect, she would lose more than 100 hours of work each month, a 40 percent cut in her income. She says the $1,000-a-month cutback might force her to lose her house.

“It would just devastate us,” she says in an interview. “I couldn’t make it if they cut my hours to 40 a week.”

She adds, “I’m angry and not only for myself. I can’t understand Governor Brown’s thinking. A lot of people are going to be forced to go to nursing homes. It doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Why should family members get overtime pay to take care of their own family members?

Like many other caregivers, Burch gave up a career to care for a family member. Moreover, since the program allows many elderly and disabled people to remain in their homes, it drastically cuts the need for expensive institutional care: The annual cost for someone in a skilled nursing facility is more than $65,000, compared with $13,000 for someone with an average number of IHSS hours, according to a 2012 report from the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The Congress of California Seniors’ Passmore says that, like any other workers, family members employed as home health care workers have a right to overtime.

“Just because they are a family member doesn’t disqualify them from having worker rights,” he says. “If you work for a family business, you still get overtime. Overtime is a fundamental worker right. Why would you not? What this argument does is diminish the important work that people [who] provide home care do.”

He adds that in many instances, the caregivers taking care of relatives have given up the opportunity for better paying jobs in order to make sure family members get the best care possible: “I know people who have sacrificed their careers because they felt, as a family member, they could provide higher quality care.”

The Obama administration’s decision to extend overtime pay to two million home care workers nationwide came after nearly two years of debate and much opposition from Congressional Republicans. Under the new regulations, home health care workers, such as those in California’s IHSS program, will be covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act. The new regulations go into effect January 1, 2015.

In announcing them, Labor Secretary Thomas Perez stated, “Today, we are taking an important step toward guaranteeing that these professionals receive the wage protections they deserve while protecting the rights of individuals to live at home.”

Brown himself has been silent on the matter and calls to his office requesting comment were not returned. His administration spelled out its opposition to including state in-home workers in the overtime protections in a May 2012 letter to the Department of Labor, and in an April 2013 letter to the federal Office of Management and Budget.

“Please be advised that we share the President’s and Department of Labor’s view that domestic care and other workers should be fairly compensated for the important services they provide,” wrote Diane Dooley, California’s Health and Human Services Agency Secretary. “However, we believe the proposed overtime rule will significantly impact the hundreds of thousands of persons who are elderly, blind and disabled that depend upon these workers for their care.”

If the overtime rule was extended, Dooley warned, the state would have two options: paying the overtime or avoiding the increased cost by not allowing providers to work overtime. The latter choice would require elderly and disabled recipients to hire supplemental caregivers to meet their needs that exceed the work-limit hours. The cost of paying overtime to IHSS providers is nearly $300 million, and doesn’t include additional millions in administrative costs to reprogram computer software programs used to track and pay IHSS workers, the letter stated. (Critics of Brown’s decision to cap caregiver hours say the figure is closer to $220 million.)

Considering the strong opposition expressed by the Brown administration while the overtime policy was being considered, it wasn’t totally unexpected that the governor’s budget proposal contains the prohibition on overtime. Nonetheless, it has already provoked controversy — labor unions and other groups have vowed to fight the overtime prohibition.

The Congress of California Seniors’ Passmore says he understands the governor’s desire for fiscal responsibility “when you do it fairly and it doesn’t create hardship.” But he says the overtime ban involving IHSS workers isn’t fair and doesn’t make sense.

“We think it’s a wrongheaded policy,” he says, adding that the state needs to come up with the funding to pay the overtime.

“I’d rather have the extra hours and not be given overtime,” says Vidales when asked about the issue. “I will have a hard time deciding who to cut back on. That’s my dilemma. I’ve been with these people for years. This is more than just a job. You become attached to these people. They count on me.”

To help others understand why paying overtime is a responsible policy, proponents point to home health care worker Kady Crick. For the last five years Crick, a 58-year-old Riverside woman, has taken care of a 38-year-old neighbor who suffers from lupus and heart and kidney problems.

“We’ve gotten to have a strong bond,” says Crick. “She’s not only my patient, she’s my friend. It would be hard to have a stranger come in because lupus [care] isn’t a science. . . . I’ve kept her out of the hospital for two years.”

Crick now takes care of her neighbor about 202 hours a month, and earns $11.50 an hour. Under the new regulations, Crick’s hours would be cut to 160 a month, about a 20 percent reduction. To make up the difference, her client would have to interview and hire a supplemental worker who doesn’t have the same familiarity with her symptoms and medical problems.

“It’s not just a job for me,” Crick says. “I care about her wellbeing, I work really hard.”

Andrea Vidales, the Atwater woman who takes care of three people in Merced County, has a similar bond with those she cares for. One of them is Juan Benjamin Roybal, a retired book seller and Navy veteran who served in the Korean War. Roybal, who is 82 years old and blind, says he trusts and depends on Vidales.

“She keeps track of my banking, she knows where all the food is,” he says, listing a few of the ways that Vidales helps him navigate his life and remain in his home.

“I wouldn’t want to have anyone other than her,” he says. “She’s indispensable.”

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care