Biden's Immigration Battle

Can Trump Administration Officials Be Prosecuted for Immigration Policies?

An adviser for Physicians for Human Rights says that immigrant family separation cases meet all four United Nations criteria for torture.

The Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy, launched in 2018, attempted to stem immigration through measures including separating migrant children from their parents at the southern U.S. border — actions that legal and human rights experts say resulted in the separation of nearly 3,000 parents from their children. Hundreds of children remain lost as of this writing, and zero tolerance was only one of a set of policies that sowed chaos and misery in the name of drastically reducing border crossings. It could leave administration officials open to prosecution.

Co-published by Newsweek

A report released earlier this year by Physicians for Human Rights concluded that the Trump administration’s family separation policies “rise to the level of torture,” which is prohibited under domestic and international law.

The authors write: “As defined by the United Nations Convention Against Torture, torture is an act 1) which causes severe physical or mental suffering, 2) done intentionally, 3) for the purpose of coercion, punishment, intimidation, or for a discriminatory reason, 4) by a state official or with state consent or acquiescence.”

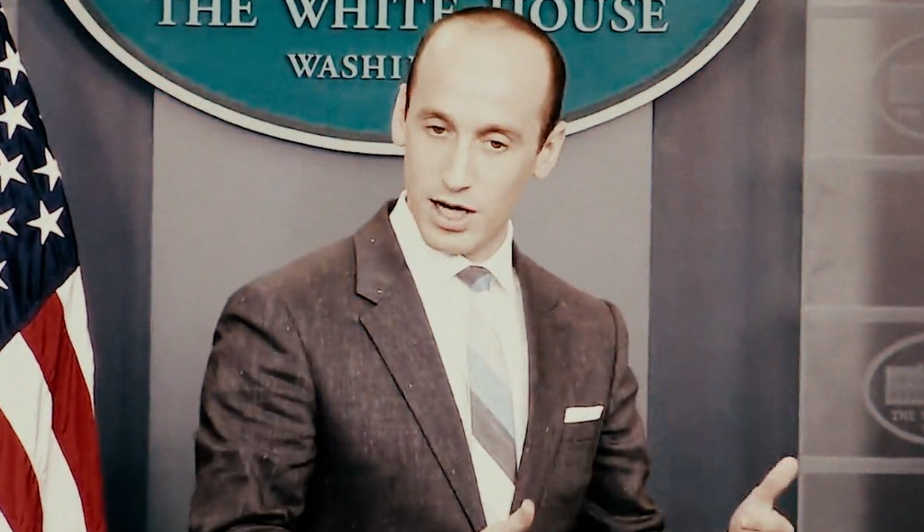

One of the report’s authors, Ranit Mishori, senior medical adviser for Physicians for Human Rights, told Capital & Main that all of the family separation cases that PHR documented meet all four criteria for torture, including statements by Trump senior adviser Stephen Miller, architect of some of the worst immigration policies in the Trump administration: the Muslim travel ban, family separation, using Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to terrorize undocumented immigrants and the attempted deportation of 700,000 “Dreamers.”

“We have [Stephen Miller], a state actor who conceived of the policy saying ‘we’re doing this to deter people from coming into the country,’ and clear evidence that they are inflicting trauma,” said Mishori. Both torture and disappearance are human rights violations, Mishori added. But according to legal experts, it may be tricky to find a legal body with jurisdiction to prosecute officials responsible for the disappearance of migrants, and other possible crimes, at the U.S. border.

Prosecuting torture in international court

Located in The Hague, in the Netherlands, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is the body responsible for trying individuals for war crimes, genocide and other crimes against humanity. If any administration figures were to be held accountable and prosecuted, the ICC would be the agency to bring the indictments.

In a blog post, Tasnim Motala, a fellow at Howard University School of Law, used an example of the ICC response to forced displacement of Rohingya Muslims by the Myanmar government to determine that the ICC could at least investigate allegations of torture against migrants at the U.S. border. But she admitted that “even if the deportation of asylum seekers on the U.S.-Mexico border meets the criteria of the crime against humanity of forced displacement, it is unlikely that the ICC will initiate an investigation into the abuses.”

The International Criminal Court could, in theory, investigate U.S. crimes perpetrated on a member country’s soil, such as Mexico.

That might be because the ICC raised the ire of the Trump administration earlier this year when it allowed an investigation into allegations of war crimes committed by the U.S. in Afghanistan.

The ICC also might pass on the torture allegations due to jurisdiction. Although the U.S. led negotiations that created the court, it was one of only seven countries — including China, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Qatar and Yemen — to not sign on to the Rome Statute, which is the treaty that established the ICC in 1998. That means the ICC has limited authority in which to investigate possible crimes in the U.S. But it could, in theory, investigate crimes perpetrated by the U.S. on a member country’s soil, such as Mexico.

Uzay Yasar Aysev, a consultant with the international legal service Global Rights Compliance, is suggesting a possible workaround to prosecuting U.S. officials, although an ICC member state, such as Mexico, would have to bring charges of violating international law.

See Other Stories in this Series

“The ICC can exercise jurisdiction over any of the crimes listed under article 5 of the Rome Statute (i.e., crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes) if at least one legal element of the crime or a part of it is committed on the territory of a State Party,” Aysev said.

“Mexico is a State Party to the Rome Statute, meaning that if it can be proven that a part of the alleged crimes committed by the United States officials have occurred in Mexico, the Court can exercise jurisdiction over the totality of the crime in question. This is regardless of whether the majority of the criminal conduct took place in the United States.”

In other words, as long as the crime “spilled” into Mexico, a State Party to ICC, the court could exercise jurisdiction over that crime, including any criminal acts that were committed in the United States.

Aysev laid out the logic of how this could happen: “Without any regard to their internationally recognized right to seek asylum and have their request for asylum reviewed, the Trump administration [has] systematically forced these victims out of the U.S. Since the victims have been deported to Mexico, this crime could be said to have partially occurred within the territory of a State Party (Mexico) to the Rome Statute.”

A Texas prosecutor could bring charges against a Trump official on behalf of a separated child or parents. That’s assuming the official doesn’t have immunity from prosecution — and very often they do.

A third reason that the ICC may never investigate alleged torture by Trump officials is because its mandate is active when national courts are unwilling or unable to prosecute criminals. So, could officials face trial in the U.S.?

Legal action in U.S. courts

If there is at least one victim, a prosecutor or private attorney in a U.S. state can bring a criminal charge against a government official, according to Claudia Flores, director of the Global Human Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. “But the criminal charges would be brought in state court depending on where torture happened,” she said.

In theory, then, a prosecutor in Texas could bring charges against a Trump official on behalf of a separated child or parents. That’s assuming the official doesn’t have immunity from prosecution — and very often they do.

According to Francisco Rivera Juaristi, founding director of the International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara University School of Law, Stephen Miller, as a senior adviser to the president, and, importantly, a government employee, is immune from prosecution.

“Under the Federal Tort Claims Act, to sue a government agent for a tort involving wrongful or negligent acts, you would have to allege that s/he acted outside the scope of her or his office or employment, in order to overcome a government employee’s absolute immunity defense,” Juaristi wrote in an email.

“I’m not saying it’s impossible to sue [Stephen Miller] personally, but that there is a high threshold.”

— Francisco Rivera Juaristi, International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara University School of Law

If Miller’s actions were within the scope of employment or office, then the tort lawsuit must be against the government itself, not Miller, Juaristi adds. “Federal employees only have qualified immunity for alleged violations of clearly established federal law and the U.S. Constitution. I’m not saying it’s impossible to sue him personally, but that there is a high threshold.”

Accountability beyond prosecutions

Until January 20, migrants and their children may still be at risk. In December CBS News reported that Customs and Border Protection officials admitted to violating a court order prohibiting the U.S. from expelling dozens of children at its southern border.

Mishori told Capital & Main that she and colleagues at Physicians for Human Rights want, at the very least, accountability — that the actions of the Trump administration will be remembered as torture.

Accountability “could mean criminal charges, or a truth and reconciliation commission. At the very least we want people who suffered to get an apology from the government, and reparations and mental health services. Of the 500 families who were separated, 628 [children] have still not been found. They all will need mental health services.”

Other groups, like the Southern Poverty Law Center, are taking a look-forward approach to ensure such immigration abuses don’t happen under future administrations. “Trump has shown a shocking level of callousness and we are hopeful Biden will move toward a fair and orderly immigration system,” said Kelli Garcia, SPLC’s policy counsel.

Before turning his justice department on anyone in the Trump administration, if he even does, President Biden first must clean up the immigration mess left behind, human rights advocates say. That requires reuniting children with their parents — difficult when the Trump administration deliberately didn’t keep records. And, says Garcia, Biden would have to restore migrants’ access to the courts so that their cases can be heard.

During the final presidential debate, then-candidate Biden declared Trump’s family separation policy “criminal,” and often has vowed to reverse many of the restrictionist policies. But President-elect Biden has made no mention of prosecuting anyone for crimes, and may be tempted to look forward, not backward, especially as a pandemic ravages the nation.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care