California Expose

Can a Business-Labor Alliance Save California’s Infrastructure?

Lucy Dunn has a message for Republican lawmakers: Approve new revenue now to fix California’s decaying highway and bridge system or face severe economic consequences that will be felt throughout the state for decades.

Dunn is no big-spending liberal and you won’t find a Proud to Be Union bumper sticker on her car. In fact, she’s president of the influential Orange County Business Council and a card-carrying Republican. But to Dunn, funding long-neglected transportation maintenance and repairs is an existential issue for California’s business community.

“If you can’t move people and goods on safe roads and bridges, you cannot do business in the state,” Dunn tells Capital & Main.

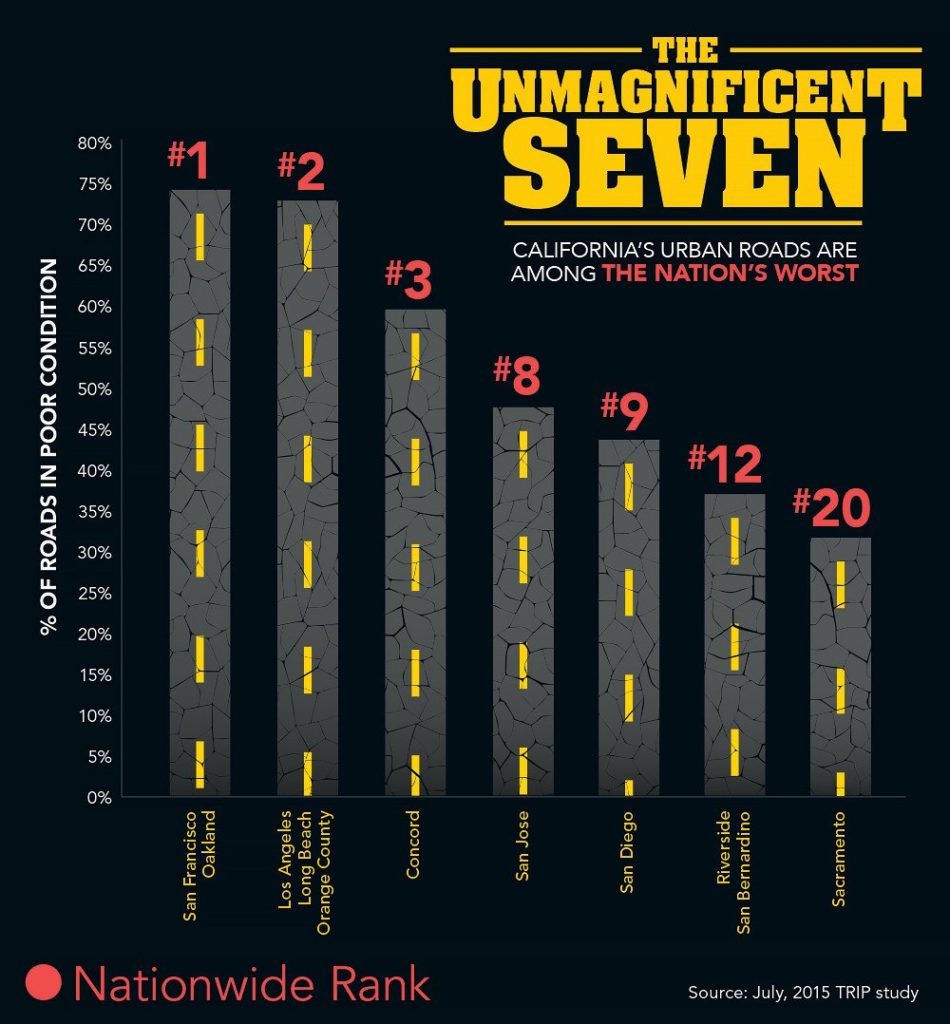

This fundamental lesson was brought to urgent life in July, when a bridge collapsed along Interstate 10 during heavy rains, cutting off the main route between California and Arizona. While no one was killed, the incident underscored the fact that California’s highways, bridges, streets and roads are in desperate need of rehabilitation, repair and maintenance. According to the California Transportation Commission, the state currently has $57 billion in deferred maintenance and ranks 45th among the 50 states for overall highway performance.

One-quarter of local streets and roads will be in “failed” condition by 2022 under current funding levels. The estimated annual cost of deficient and congested roads, and traffic accidents in California is $44 billion – nearly $2,500 per motorist annually, the commission says. Furthermore, more than one-fourth of California’s bridges are in need of repair, improvement or replacement, 11 percent of the state’s bridges are structurally deficient, and 17 percent are functionally obsolete.

“There clearly needs to be more money invested in transportation infrastructure,” says the commission’s executive director, Will Kempton. “It’s similar to taking care of a leaky roof. The longer you wait, the more it costs.”

Governor Jerry Brown has made transportation improvements a priority and this summer called a special session of the legislature to deal with it. Late last week he offered a plan for $3.6 billion in yearly funding that would partly be financed by a $65 fee for vehicle owners, an 11-cent hike in the diesel tax and a six-cent increase to the gas tax. Other money would be allocated from California’s cap-and-trade carbon emissions program.

The plan appears to have strong support among Democrats in Sacramento. However, Republicans, while generally agreeing that the state’s roads need to be fixed, have offered their own plan that vaguely calls for greater government efficiency and accountability, while specifically demanding layoffs of workers at Caltrans, the state’s Transportation Department. But no new taxes.

Even if all Democrats vote for new infrastructure taxes as the state legislature enters its final week of the current session, at least one Republican state Senator and two Republican Assembly members would be needed for passage because a two-thirds majority is required to raise taxes. Those Republican votes are far from certain. “Even in Orange County they’ve all signed pledges not to raise taxes.” acknowledges Lucy Dunn of efforts to persuade GOP legislators.

“Right now, I’m opposed to [new] taxes,” Assemblymember Rocky Chávez (R-Oceanside) says in an interview with Capital & Main. Chávez is an announced candidate to replace the retiring Barbara Boxer in the U.S. Senate. “Just saying ‘raise taxes’ is not a solution.” He adds, “I know there is a serious problem.”

Not even the state’s business leaders deny there can be a solution without raising taxes.

“We know money doesn’t grow on trees and funding has to come from somewhere,” says Ruben Gonzalez, senior vice president for public policy and political affairs with the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce. “The business community has no problem investing in needs as long as we are given confidence the money we are investing is going to products and outcomes we were promised.”

Adding their voices to the infrastructure debate last month, a coalition of business and labor groups stated in a letter to Governor Brown and legislative leaders that “any package should seek to raise at least $6 billion annually and should remain in place for at least 10 years.” Coalition members range from the California Chamber of Commerce to the State Building and Construction Trades of California to the League of California Cities.

The fight over transportation funding highlights a growing political chasm between Big Business and its traditional Republican allies in Sacramento. It also raises the possibility that Republican lawmakers will torpedo historic investments in highway and bridge repairs and maintenance, to the detriment of the state’s long-term economic interests and their own districts’ needs.

Jim Earp, executive consultant for the California Alliance for Jobs, says that it is imperative to find a way to gain a few Republican votes. “We’re not trying to get the blessing of the entire Republican caucus,” he says. “We are really focusing on legislators who have districts [whose roads] are in particularly tough shape.” He declines to name any specific legislator whose vote is being targeted.

Proponents point out that raising revenue for the needed transportation fixes would create thousands of new jobs, because it takes men and women to fix the roads and provide engineering and other services. John Casey, spokesman for outgoing Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), says that studies show that every $1 billion spent on road improvements creates 13,000 to 15,000 new jobs. If $6 billion per year in new money is approved, that could create 80,000 jobs alone, he says.

Ruben Gonzalez of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, agrees. “It’s the old saying. Time is money. If you don’t have good roads, you’re causing delays and inefficiency. That costs money – money that could be used to create jobs. This is all about jobs.”

In many ways, the current battle over transportation funding in California reflects the nationwide trend towards politicizing issues that were historically dealt with in a bipartisan way.

“To make roads and bridges safe, to make sure our ports can compete – these should not be issues that one party or another supports,” says Edward Wytkind, president of the Transportation Trades Department, AFL-CIO, a Washington, D.C. labor organization representing transportation-sector unions. “These are symbols of a modern economic power.”

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.