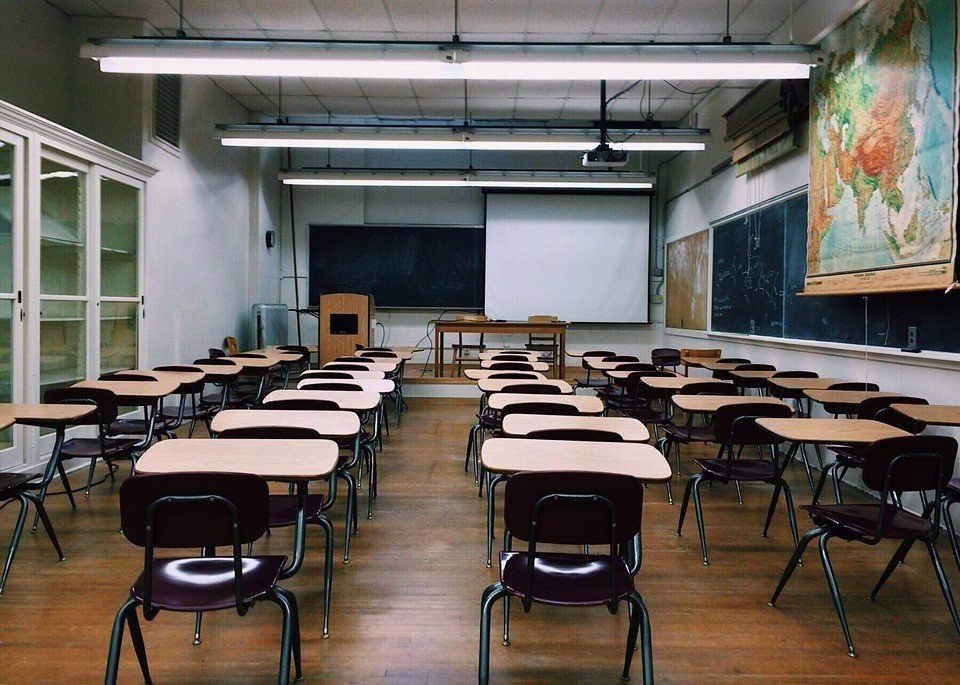

Education

California’s Failing Grade in Charter School Facilities Financing

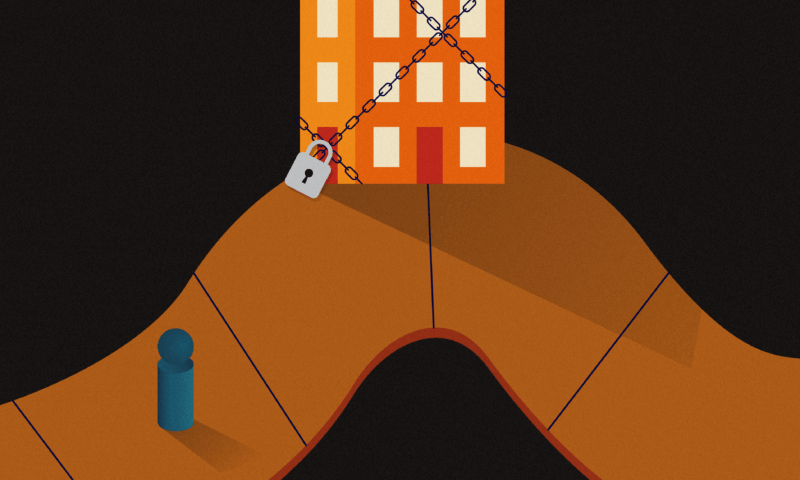

A new study shows that tax dollars have been used to create privately held real estate empires — charter school properties that, because they aren’t owned by the public, could, theoretically, one day be converted into luxury condominiums or shopping complexes.

A new study of public charter school funding has found that California’s explosive charter growth of the past 15 years has left school districts straining under a glut of new charter classrooms that are no better at educating California children than traditional public schools. Released Monday by the research and public advocacy group In the Public Interest (ITPI), Spending Blind reveals the extent to which tax dollars have been used to create privately held real estate empires — charter properties that, because they aren’t owned by the public, could, theoretically, one day be converted into luxury condominiums or shopping complexes.

Subtitled, The Failure of Policy Planning in California Charter School Funding, the report zeroes in on the costs and impacts of the $2.5 billion in charter school construction and rent subsidies that has been made available to prospective charter operators in a taxpayer-subsidized system of 10 state and federal public funding programs mostly administered by the California School Finance Authority (CSFA).

The report found that the facilities-funding programs had unintended effects, particularly that they

- Incentivized adding classroom space to districts that didn’t need it.

- Created charter schools that underperformed in comparison to their traditional public school neighbors.

- Funded charters that in hundreds of cases were later found to have discriminatory enrollment policies.

- Paid for privately owned real estate enterprises.

- Enabled some of the state’s charter school scandals of last year.

The charter school industry relies upon a system of state and federal grants, loans, tax credits, and state and district bonds to pay for classroom space. Spending Blind represents the first time, its author, political economist Gordon Lafer, told Capital & Main, that this system has been subjected to the kind of cost-benefit questions that the public school side of the equation is typically required to answer.

“The most surprising discovery was just the total disconnect between the education policy goals of creating charter schools – [that] I think are still pretty much what people think is the point of charter schools – and how that money is spent,” said Lafer, who is also an associate professor at the University of Oregon’s Labor Education and Research Center. “I expected that it would be like, you know, ‘We have these goals, we write the goals into funding.’ Instead, it was a total disconnect.”

Charter schools are financed with the same taxpayer dollars that pay for public schools, but are managed by private companies. Passed in the early 1990s, the state’s original charter law created the charter school of the popular imagination — a statutory zone of deregulation that allows boutique schools to develop superior curricula geared to persistently low-performing students.

But beginning in the late ’90s, a flurry of changes to the law included generous facilities subsidies that effectively opened the door to charter management organizations (CMOs) — scaled-up corporate franchises whose overall performance has roughly mirrored that of existing public schools. From having fewer than 200 charters in 1998, California now boasts 1,230 schools with 581,100 students, giving it the largest charter enrollment in the nation. The California Charter Schools Association (CCSA) has vowed to nearly double that number by 2022.

In a prepared statement, CCSA brushed aside the report’s findings as an attempt to generate support for Senate Bill 808, a charter school reform measure authored by State Senator Tony Mendoza (D-Artesia). It also accused ITPI of a “well-documented and biased point of view on the role charter schools play in the public education system.”

Nevertheless, Lafer found that public facilities funding has been disproportionately concentrated among the fewer than one-third of schools that are owned by CMOs of between three and 30 schools. And it pointed to the state’s four largest California CMOs — Aspire, KIPP, Alliance and Animo/Green Dot — as claiming an even more disproportionate share.

Lafer also alleged that Los Angeles’ Alliance College-Ready Public Schools network of charter schools also led the big CMOs in using public facilities financing to build up subsidized inventories of private real estate. Lafer’s study reports that Alliance alone has translated $110 million in federal and state taxpayer support into a portfolio of privately owned property “now worth in excess of $200 million.”

“I don’t think anybody in the legislature ever intended — and I wouldn’t think most citizens or taxpayers intended or would approve of the idea —that public tax dollars are going to be used to buy somebody private property,” Lafer said.

Yet California charter schools can become the private property of a charter operator when they are paid for with proceeds from the state’s three public conduit bond programs offered by the CSFA, the California Municipal Finance Authority (CMFA) and the California Statewide Communities Development Authority (CSCDA). An operator could also get the same result using private funding subsidized by California’s New Market Tax Credits program, or by getting the school’s mortgage payments reimbursed through CSFA’s Charter School Facilities Grant Program, more commonly known as SB 740.

Should the authorizer revoke the charter, the state and the local school district would be left scrambling to house displaced students. The now-unencumbered former charter operator, however, would be free to turn the buildings into luxury condominiums or sell them at a profit.

The danger, Lafer explained, is that because there is no meaningful cap written into California’s education code, any CMO bent on aggressive expansion could effectively become too big to fail. If a privately owned chain expands into a General Motors-like behemoth, then one day goes irredeemably bad, the district would be faced with the staggering cost of replacing those privately owned classrooms.

“You potentially lose those choices if the price of making those choices is prohibitively high,” Lafer explained. “And the more of this [facilities financing] that happens, the closer to that situation we get.”

That scenario is more than theoretical. Tri-Valley Learning Corporation (TVLC) might be the poster child for California’s taxpayer subsidy program. It is one of three California case studies that Lafer features from last year’s charter scandals. The school, which operates two charters in Livermore and two in Stockton, collapsed last November after a run of poor managerial and financial decisions that included taking on $70 million in charter facilities bond debt. Though its schools are still technically open for business, the company’s death rattle continues to echo in Stockton, where both TVLC charters, Acacia Elementary school and Acacia Middle school, will be shuttered in May.

The story of the Tri-Valley Learning Corporation will be the focus of a Capital & Main feature later this month.

-

Locked OutDecember 16, 2025

Locked OutDecember 16, 2025This Big L.A. Landlord Turned Away People Seeking Section 8 Housing

-

Locked OutDecember 23, 2025

Locked OutDecember 23, 2025Section 8 Housing Assistance in Jeopardy From Proposed Cuts and Restrictions

-

The SlickDecember 19, 2025

The SlickDecember 19, 2025‘The Poor Are in a Very Bad State’: Climate Change Accelerates California’s Cost-of-Living Crisis

-

Locked OutDecember 17, 2025

Locked OutDecember 17, 2025Credit History Remains an Obstacle for Section 8 Tenants, Despite Anti-Discrimination Law

-

Latest NewsDecember 22, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 22, 2025Trump’s War on ICE-Fearing Catholics

-

Column - State of InequalityDecember 18, 2025

Column - State of InequalityDecember 18, 2025Beyond Hollywood, Rob Reiner Created Opportunity for Young Children Out of a Massive Health Crisis

-

Striking BackDecember 17, 2025

Striking BackDecember 17, 2025‘There’s Power in Numbers’

-

Column - State of InequalityDecember 24, 2025

Column - State of InequalityDecember 24, 2025Where Will Gov. Newsom’s Evolution on Health Care Leave Californians?