Immigration

California Pardons Help Former Prisoners Beat Deportation

Facing deportation to homelands they barely remember, formerly incarcerated Southeast Asians in L.A. are fighting in court to remain here.

The threat of detention and eventual deportation is a major challenge facing some formerly incarcerated Los Angeles residents of Southeast Asian origin. Some have fought their detention and deportation orders by appealing to have their cases removed in court — where few things carry more weight than governor-granted pardons for past crimes

Co-published by Voice of America

“A pardon really validates all the things I’ve done to turn my life around,” said Houth “Billy” Chhang Taing, who received a pardon in 2018 from then-Gov. Jerry Brown. Taing used it as grounds to successfully fight his deportation to Cambodia, a country he feared returning to after having escaped from there as a child refugee.

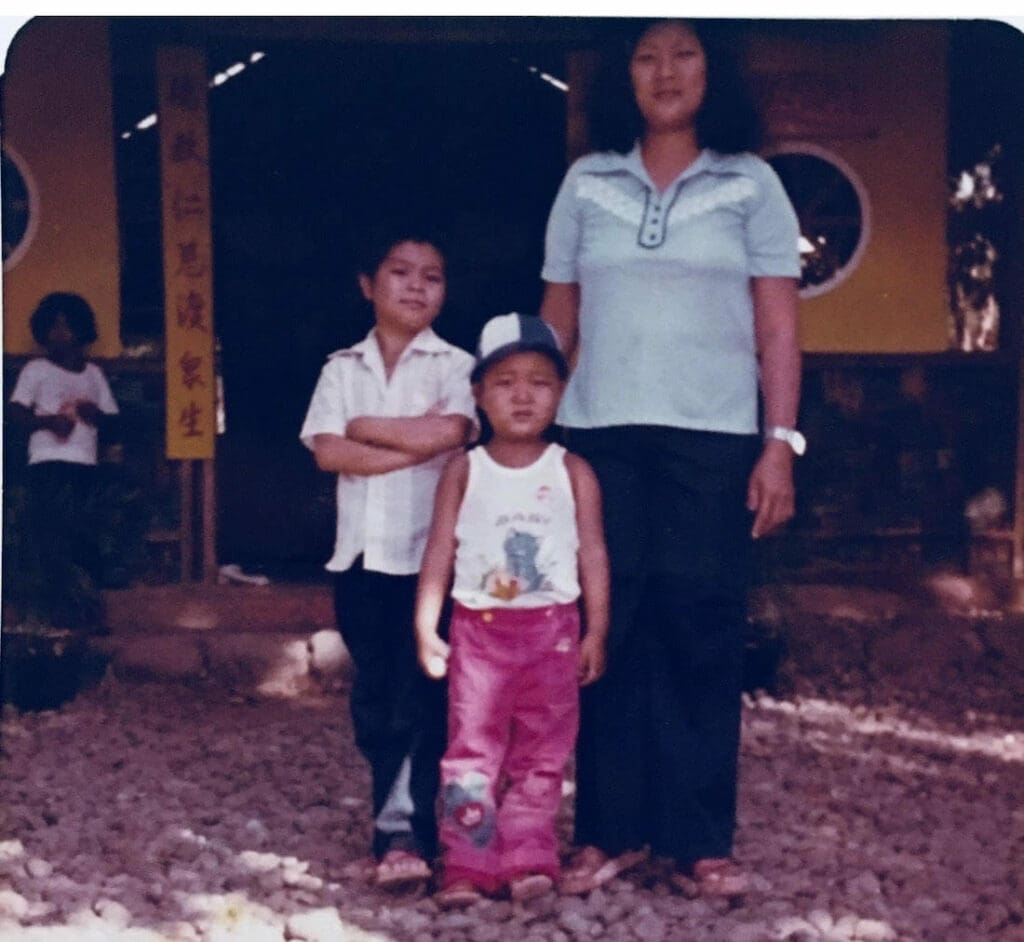

Taing was born in Cambodia to Chinese parents under Khmer Rouge rule in the 1970s. When Taing was only a year old, his father was targeted for his ethnicity after he was overheard speaking a Chinese language. He was beaten and taken away, and the family never saw him again.

Taing’s mother and older brother were subjected to torture in a forced labor camp, and after a month-long journey that involved crossing mine fields, the family was able to escape to a refugee camp in Thailand. They then lived in a camp in the Philippines before eventually coming to the U.S. when Taing was 5.

As a young man growing up in L.A., Taing said, he was “living a double life.” One was at home with his mother and brother, attending high school and then serving in the Army National Guard. Another was the gang lifestyle in his Monterey Park neighborhood.

In 1994, when Taing was 19, he and two others hijacked and robbed a tour bus on its way to Las Vegas. He was caught by police and charged with kidnapping and robbery while in possession of a firearm. Taing was given two life sentences, of which he served 21 years in prison.

He was released in 2015, yet then detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement for four months. At the time, Cambodia did not recognize him as a citizen, and he was released, but was under an order of supervision by ICE and required to wear an ankle monitor to track where he went.

Then, in 2018, the Cambodian government resumed an agreement, begun in 2002, in which the nation would accept Cambodian nationals who were deported by the U.S. for having criminal records.

Many of them were infants when they fled the Khmer Rouge or had been born in Thai refugee camps. For the majority of their lives, they have known only the United States as home, and some have no contacts or resources in the countries to which they are deported.

In 2017, Taing was detained yet again, this time for six and a half months. He said that in ICE detention, as in prison, the individual is seen as only a number and not as a person. What makes the experience much worse, Taing said, is that, unlike in prison, no one knows when they will be released.

“Many people in detention [were] just resigned to being deported and didn’t think they could fight their case. They thought at least they would be free in another country,” Taing said. After he was released, Taing felt he had to fight to stay in the U.S., the only country he calls home. After years in prison, he wanted to help his aging mother and his younger brother, who now has a family.

“It is double jeopardy to be deported,” Taing said, claiming that even after serving his sentence, he is being punished again by having his immigration status challenged.

* * *

On November 14, California Gov. Gavin Newsom pardoned three formerly incarcerated people in order to prevent them from being deported to Vietnam and Cambodia. Formerly incarcerated nationals of other Southeast Asian countries pray for pardons too.

Maria-Elena Luna, who served 23 years in prison, is hopeful a pardon will be granted after her application was accepted. Like Taing, she fears for her safety if she’s deported, and also hopes that a pardon, with the social justice work she has done since her release from prison, will buttress her clean record.

Luna had been unaware she had moved to the U.S. from the Philippines when she was 3 years old, and always thought she had been born in California. She discovered the truth while serving time in a California prison, but did not believe it was true until she was detained by ICE the day she was released from the California Institution for Women in Corona.

Luna has a valid green card but is seeking a pardon. She worries that her criminal past will make her a target of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, whose war on drugs has seen a wave of extrajudicial killings of suspected drug dealers and users.

Phal Sok: “It was a lot of work to get this pardon.”

In contrast, Phal Sok had his deportation order to Cambodia dismissed in November 2018 after having been granted a pardon by Gov. Brown the previous August. Sok, who is of Cambodian ethnicity, was born in a Thai refugee camp and given U.S. residency status as a refugee in Los Angeles when he was less than a year old. In 1999, when he was 17, he was tried as an adult and sent to prison for three counts of robbery with a firearm. He was unaware that this conviction put his green card in jeopardy, and ICE detained him when he was paroled in 2015.

“I felt a sense of relief, but it was a lot of work to get this pardon. I had to get a lot of endorsements from community folks and legislative officials, such as state assembly people and members of Congress,” Sok said.

The pardon was granted to him based on his social justice work at the Youth Justice Coalition, which advocates for policy change to help young people in the justice system. The pardon helped Sok get his green card back in November 2018, and he plans to apply for U.S. citizenship to be able to travel outside the country. Although his supervision order has been terminated, he says he still feels constant anxiety from a little over two years of required check-ins with ICE.

* * *

“We committed our crime and paid our time,” Billy Taing said. When he can, Taing stays active in the nonprofit Asian Pacific Islander Reentry and Inclusion Through Support and Empowerment (API RISE), which helps former inmates reenter society.

Taing was nervous before his October 8, 2019, check-in with ICE at L.A.’s downtown Federal Building. Every time he checked in with the agency, he had no idea if he would be detained on the spot again or even deported. “Checking in could [mean] going in and not coming back out. I could lose my job, not even having done anything wrong,” Taing said. He currently works as an electrician.

“We committed our crime and paid our time. I can evolve as a human being. I’m not just a number.”

— Ex-felon Houth Chhang Taing

The previous year his petition for a stay of removal for deportation had been denied. But then came Gov. Brown’s pardon at the end of 2018. After his October check-in, he was given a six-month extension. ICE Los Angeles assistant field office director Christian G. Menjivar said the removal process is straightforward across the board and is not based on someone’s nationality, adding that all factors in each case are reviewed individually.

Deportation is considered, Menjivar said, for someone who has committed an “egregious crime,” such as assault, murder, rape, a crime against a child, or an aggregation of minor crimes. Even if the individual served his or her sentence in the U.S. many years ago, the person can still be considered for detention and deportation if the case is deemed egregious.

Taing said his situation is better than others, since he received his pardon in 2018. Lawyer and API RISE co-founder Paul Jung, who helped Taing with his pardon application, remembers the afternoon Taing learned he was given a pardon.

“We were cautiously optimistic when he got the call…. There was a sense of relief and a bit of surprise,” Jung said. The pardon nullifies the criminal conviction, although it does not expunge Taing’s record. Jung said the pardon would help Taing in immigration court, because the primary bases for deportation are his felonies.

With this pardon, Taing had grounds to reopen his deportation case and petition because his convictions are no longer a valid reason for him to be deported. He credits the pardon as a major factor in his case being closed by the board of immigration appeals on February 27, 2020. Taing now plans to apply for U.S. citizenship.

A pardon by the governor is no assurance that detention or deportation efforts will cease, but for those formerly incarcerated members of L.A.’s Southeast Asian community, it is seen as a way to validate efforts made to rehabilitate themselves. “I’m someone who can evolve as a human being. I’m not just a number,” said Taing.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care