Opinion

Are Picket-Crossing Dodgers Cursed?

Marvin Miller, who freed Major League Baseball players from virtual serfdom, would be angry as hell at the team’s behavior in Boston.

This week the Los Angeles Dodgers forgot Labor Rule #1 in Boston: Never cross a union picket line.

The last time the Dodgers played the Red Sox in the World Series was in 1916, when Boston won.

Now, after 102 years, the two teams are meeting in the World Series again. So far, things don’t look good for the Dodgers, who dropped the first two games, played in Boston’s Fenway Park. Blame it on disappointing pitching, hitting and fielding. But there’s another element that you won’t see in the box scores: The curse of Marvin Miller.

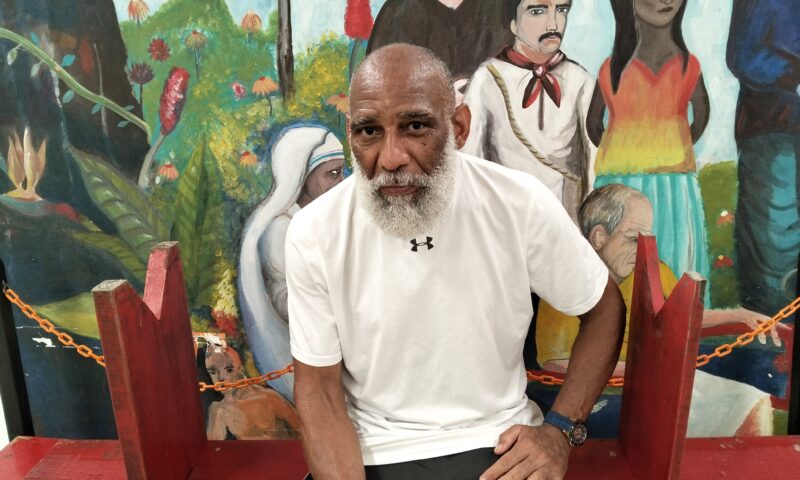

As the first executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) from 1966-83, Miller made the MLBPA the most successful union in the country. Before Miller, players were tethered to their teams through the reserve clause in every player’s contract. Players had no insurance, no real pensions and awful medical treatment.

“People today don’t understand how beaten down the players were back then,” Miller told us in 2008, four years before he died. “The players had low self-esteem, as any people in their position would have—like baggage owned by the clubs.”

With Miller’s guidance, the players union negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement in 1968. In 1976, they gained the right to become free agents, allowing players to decide for themselves which employer they wanted to work for. In 1967, the year after Miller took the helm, the minimum salary was $6,000 ($45,984 in today’s dollars) and the average salary was $19,000 ($145,616). This year the minimum salary is $545,000 and the average salary is $4.5 million.

Miller came to the MLBPA after a long career with the United Steelworkers of America, and brought baseball players respect and money through his tough negotiations with team owners and emphasis on player solidarity. He educated the players that they were part of the broader labor movement and to respect the struggles of other union members and people who weren’t as fortunate as themselves. That included Rule #1 – Never cross a union picket line.

This week, the Dodgers forgot that lesson in Boston, when they crossed the picket line at the Ritz Carlton Hotel, where housekeepers, cooks, doormen and other hotel workers are on strike. UNITE HERE’s 1,500 members walked out October 3 at seven Boston Marriott-owned hotels, including the Ritz-Carlton. The union is calling on Marriott to provide steadier hours so that workers will have health insurance, higher pay, more job security — and pension protections for employees approaching retirement. (Over 8,000 workers at Marriott-run hotels in eight cities are currently on strike).

Dodgers executives had plenty of advanced warning. Two weeks ago the New York Yankees, whom the Red Sox bested in the American League Division Series, also crossed the Ritz-Carlton picket line, generating lots of media attention and angry condemnations from union leaders.

UNITE HERE Local 26 in Boston had tried to steer the Dodgers toward another union hotel, but the team’s executives ignored them.

The Dodgers should not have put their players in the uncomfortable position of crossing another union’s picket line. This should be particularly embarrassing to Magic Johnson and Billie Jean King, part-owners of the Dodgers who, in their own lives, have been activists for social justice.

They and the other Dodgers owners and executives knew that having their players cross the workers’ picket line would cause controversy. That’s why the team’s brass instructed the players to enter the Ritz-Carlton through the back door to avoid publicity.

But the ploy didn’t work. The Boston papers, radio talk shows, TV news and blogs were filled with nasty comments that went far beyond the rivalry on the baseball diamond. They called the Dodgers “scabs” and “strikebreakers.”

Ironically, the strike’s slogan, “One Job Should Be Enough,” could have been used by professional baseball players before Marvin Miller arrived to run the MLBPA. Most had to work second jobs in the off-season to make ends meet. The hotel workers are fighting for what the baseball players once fought for.

“Jackie Robinson is rolling over in his grave, now that members of his team are crossing the picket line,” said Brian Lang, president of UNITE HERE Local 26. “The Dodgers ought to take his number down. He stood up for justice.”

The players should be sympathetic to the hotel workers’ plight. If they knew their baseball labor history, they’d know that the battles to win better salaries and working conditions were contentious. Five times – in 1972, 1980, 1981, 1985 and 1994 — the MLBPA resorted to going on strike. During the 232-day 1994 strike, the Teamsters union refused to deliver food and other supplies to major league stadiums.

Baseball has enjoyed labor peace since then and today’s players are the beneficiaries of those actions. But last January, Dodger pitcher Kenley Jansen – concerned that team owners were colluding to keep free agents unsigned in order to reduce their bargaining power and give players a declining share of team revenues — suggested that the players might have to consider another work stoppage.

“Maybe we have to go on strike, to be honest with you,” Jansen said.

Despite those sentiments, Jansen, like his teammates, crossed UNITE HERE’s picket line in Boston.

But the Dodgers still have a chance to redeem themselves – and extract themselves from the curse of Marvin Miller.

If the best-of-seven series hasn’t been decided after three games in Dodger Stadium, the teams will return to Boston next Tuesday and Wednesday to play potential Games 6 and 7.

Before then, the Dodgers’ management should make arrangements for the team to stay in one of Boston’s many union hotels where the workers are not on strike. The players – and their union – shouldn’t complain if they have to divide the team between two or three different hotels. That’s hardly a big inconvenience for millionaire athletes –- many from working-class backgrounds -– to show their support for housekeepers, waitresses and cooks who struggle from paycheck to paycheck to make ends meet.

It would also be a nice gesture if a few Dodger players expressed their solidarity by joining the hotel workers’ picket line, even if only for a few minutes. That photo op would go a long way to putting the Dodgers back in the good graces of their 800,000 fellow union members in Los Angeles County who, thanks to the labor movement, can afford to go to games at Dodger Stadium.

Only three of the 26 cities with major league teams—Cincinnati, Tampa and Arlington, Texas—don’t have union hotels. To avoid putting major league players in this situation again, the MLBPA should fight to insert language in their union contract that requires teams to stay in union hotels and to prohibit teams from staying in hotels where workers are in the middle of labor disputes, so players don’t have to cross picket lines.

Marvin Miller would be proud.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

StrandedNovember 25, 2025

StrandedNovember 25, 2025‘I’m Lost in This Country’: Non-Mexicans Living Undocumented After Deportation to Mexico

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025Santa Fe’s Plan for a Real Minimum Wage Offers Lessons for Costly California

-

The SlickNovember 24, 2025

The SlickNovember 24, 2025California Endures Whipsaw Climate Extremes as Federal Support Withers

-

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025Home Care Workers Are Losing Minimum Wage Protections — and Fighting Back

-

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025This L.A. Museum Is Standing Up to Trump’s Whitewashing, Vowing to ‘Scrub Nothing’

-

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025Is the Solution to Hunger All Around Us in Fertile California?

-

The SlickDecember 2, 2025

The SlickDecember 2, 2025Utility Asks New Mexico for ‘Zero Emission’ Status for Gas-Fired Power Plant

-

Latest NewsDecember 1, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 1, 2025Accountable to No One: What 1990s L.A. Teaches Us About the Trump Resistance