Labor & Economy

A Movement Raises the Minimum Wage and Changes the Debate

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray used last May Day to announce that business and labor had agreed to a historic plan to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Seattle’s bold measure is part of a growing wave of activism and local legislation around the country to help lift the working poor out of poverty. The gridlock in Washington – where Congress hasn’t boosted the federal minimum wage, stuck at $7.25 an hour, since 2009 – has catalyzed a growing movement in cities and states.

The Seattle victory was a game-changer. Within months, politicians in other cities jumped on the bandwagon. San Diego city officials voted in August to adopt a $11.50 an hour by 2017. In San Francisco, which already has a citywide minimum wage, voters will decide in November whether to raise it to $15.

On September 24, the Los Angeles City Council voted by a 12 to 3 margin to require large hotels to pay at least $15.37 an hour to their workers. The momentum for change created some unlikely allies for L.A.’s labor-led progressive movement. Although the local Chamber of Commerce opposed the plan, two of Los Angeles’ most politically-connected business leaders – Democrat Eli Broad and Republican Rick Caruso – told the Los Angeles Times they favored the idea. (Los Angeles, which already has a living wage law that covers employees for companies that get city contracts and workers in hotels near LAX airport, pegged at $10.91 or $15.67 without health benefits.)

Seeking to take advantage of this momentum, LA Mayor Eric Garcetti has proposed adopting a citywide minimum wage that would begin at $10.25 next year, increase to $11.75 in 2016 and $13.25 in 2017, and rise with inflation after that. He called it “the biggest anti-poverty program in the city’s history.” According to an analysis commissioned by the mayor’s office and conducted by researchers from UC Berkeley, Garcetti’s plan would increase incomes for an estimated 567,000 workers by an average of $3,200, or 21 percent, a year. Predictably, the LA Chamber of Commerce warned that “this proposal would actually cost jobs, would cause people to lose jobs and would cause people to have cutbacks in hours.”

The battle in Seattle began last year. In November 2013, voters in the suburb of SeaTac approved a union-sponsored Good Jobs Initiative’ to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour for workers in Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and at airport-related businesses, including hotels, car-rental agencies, and parking lots. The new law applied to only 6,000 workers, but the victory had huge ripple effects. Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn and his chief challenger Murray (a gay state legislator best known for leading Washington’s campaign for sex-same marriage) both supported the SeaTac initiative and raised the possibility of doing the same thing in Washington’s largest city.

On the same day that the SeaTac measure won, so did Murray and Kshame Sawant, a socialist candidate for Seattle City Council who had made the $15/hour minimum wage a centerpiece of her campaign. After his victory, Murray followed through. He appointed a 24-person Income Inequality Committee – co chaired by Howard Wright, CEO of Seattle Hospitality Group, and David Rolf, president of SEIU Local 775, who had been a major force behind the minimum wage proposal.

Rolf was adept at playing the inside/outside game. While pushing to forge an agreement among the task force members, he worked with Seattle’s labor movement and community activists to keep the pressure on city officials and to keep the issue in the media. He made sure that economists and other experts were available to educate the public, politicians, and journalists and to rebut the business leaders’ warnings that the $15 minimum wage would kill local jobs.

Both Rolf and Mayor Murray discovered that socialist Sawant was a useful, though unpredictable, ally. She was working with a group called 15 Now that threatened to put an initiative on the November 2014 ballot to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour on January 1, 2015 for all businesses. Murray told business leaders that unless they reached an agreement with the unions, he would announce his own plan that was closer to Sawant’s proposal than the phased-in plan that was being discussed in the mayoral task force.

The SeaTac referendum was nullified in court on a technicality, but in Seattle the progressives clearly had the political momentum. Even after a series of compromises, the unions and their allies won a huge victory. They agreed to a three- to seven-year phase-in, with large businesses — those with at least 500 workers — required to reach the $15 wage first.

In 2004, San Francisco and Santa Fe, New Mexico were the first two localities to adopt citywide minimum wage laws, now $10.74 and $10.66, respectively. Then, in November 2013, 66 percent of the voters in Albuquerque, New Mexico, voted in favor of establishing a citywide wage that would automatically adjust in future years to keep up with the rising cost of living; it is currently $8.60 an hour. That same day, 59 percent of voters in San Jose, California approved a citywide $10 an hour wage that would also increase with the cost of living. The San Jose victory created a regional momentum. Last May, the City Council of Sunnyvale – a San Jose suburb of over 140,000 residents – voted by a 6-1 margin to establish a local minimum wage of at least $10/hour, and to increase it annually with the cost of living. That same month, in a remarkable display of regional cooperation, Washington, DC and its suburban neighbors, Montgomery and Prince Georges County, Maryland, all adopted laws establishing a minimum wage of $11.50. The joint efforts was forged to counter business warnings about an exodus of jobs if the nation’s capital moved on its own. In 2012, Long Beach, California voters passed a ballot measure that raised the minimum wage for hotel workers in that tourist city to $13 per hour and guarantees hotel workers five paid sick days per year.

Last November New York City voters gave progressive Democrat Bill de Blasio a landslide victory over Republican Joe Lhota. One of de Blasio’s key policy planks was addressing the proliferation of low-wage jobs in America’s largest city. enacting a living wage of $11.75 per hour for workers employed by companies that get tax breaks and other subsidies from the city. Last Tuesday, by executive order, he expanded the city’s existing living wage law from $11.90 per hour to $13.13 per hour for workers at companies that receive more than $1 million in city subsidies. He also included commercial tenants of those companies in the law; as a result, retail workers inside projects subsidized by the city will also be paid the higher wage. De Blasio also eliminated an exemption for part of the Hudson Yards megaproject being on Manhattan’s West Side built by Related Companies, a politically-connected developer.

In May, the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors – an area with 1.8 million residents that includes San Jose and Silicon Valley high-tech corridor – voted to create a living wage that would affect county workers and those employed by companies contracted by the county (although they still had to agree on a wage level), and include health care, job security and other quality-of-life requirements.

Nineteen states now have minimum wages over $7.25 an hour, 10 of which automatically increase their minimum wages with inflation. Last November, even as New Jersey voters were giving conservative Republican Gov. Chris Christie a second term, they also overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment to raise the state’s minimum wage by a dollar to $8.25 an hour. The new law includes an automatic cost-of-living increase each year.

The highest state wage law is in Washington State, where the minimum wage increased to $9.32 last January and will rise to $9.47 at the start of 2015. Last year, In September, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation that raised the state’s minimum wage from $8 to $9 an hour this year and to $10 an hour in 2016. (Brown had vetoed the same bill a year earlier). In March, Connecticut lawmakers passed, and the governor signed, a bill to increase a state’s minimum wage to $10.10 an hour by 2017. In Montgomery County, Maryland – outside Washington, DC – the county council just voted to increase the minimum wage to $11.50 over the next four years.

In November, voters in South Dakota will go to the polls to decide whether to adopt a statewide minimum wage of $8.50 an hour. If it is approved, about 34,000 workers – who now make from $7.25 (the federal minimum) to $8.50 – will get pay raises, according to a study by the South Dakota Budget and Policy Institute.

Activists in other states are gathering signatures to put minimum wage hikes on the ballot and pushing state legislators to raise the minimum wages in their states, too.

This upsurge in government-mandated wage hikes hasn’t come about suddenly. It is the result of years of both changing conditions, effective grassroots organizing, and changing public views about the poor.

Throughout his presidency, Ronald Reagan often told the story of a so-called “welfare queen” in Chicago who drove a Cadillac and had ripped off $150,000 from the government using 80 aliases, 30 addresses, a dozen Social Security cards and four fictional dead husbands. Journalists searched for this welfare cheat and discovered that she didn’t exist. Nevertheless, Reagan kept using the anecdote to demonize the poor.

Reagan’s bully pulpit, and the increasing success of right-wing think tanks and writers in dominating public discussion about poverty, led to a protracted political debate about welfare. To show that he was a different kind of Democrat, Clinton campaigned in 1992 to “end welfare as we know it,” in part by “making work pay.” Congress enacted so-called welfare reform in 1996, limiting the time people can receive assistance.

Although liberals understandably decried this approach, it ironically helped shift public opinion and stereotypes about the poor. According to historians and sociologists, the public distinguishes between the “undeserving” and the “deserving” poor. The latter are viewed as more responsible, hard-working, and victims of circumstances beyond their control. Increasingly, Americans came to view low-income people as the “working poor,” a group considered more sympathetic than the so-called “welfare poor.”

In the 1990s, the mainstream news media began to pay more attention to the working poor, while academics and journalists expressed growing concern about the “Walmart-ization” of the economy – the growing number of low-wage jobs with few benefits. In 1999 Barbara Ehrenreich published an article in Harper’s magazine that two years later became her bestselling book, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, recounting her experiences toiling alongside hard-working low-wage employees who couldn’t make ends meet.

But it took effective grassroots organizing to translate these changing sentiments into public policy.

Progressives and Socialists advocated for minimum wages – sometimes called a “fair” or “living” wages – in the early 1900s. Their activism paved the way for state laws and eventually the adoption of the federal minimum wage in 1938. That law requires Congress to set the federal minimum wage, which reflected the partisan and ideological swings. In terms of purchasing power, the federal wage reached its peak in 1968 – $1.60 an hour back then, but $10.69 in purchasing power today.

The federal wage rarely came close to putting workers above the poverty line. In 1994, it had sunk to $4.25 — or $7.31 in today’s dollars. Congress hadn’t raised the threshold in three years, despite rising living costs.

Frustrated by Congressional inaction, a coalition of community organizations, religious congregations, and labor unions in Baltimore – called BUILD – mobilized a successful grassroots campaign to pass the nation’s first “living wage” law in 1994. It required companies with municipal contracts and subsidies to pay employees decently. The movement was not only motivated by stagnating wages but allow by the city governments efforts contract public services to private firms paying lower wages and benefits than those that prevailed in the public sector.

The idea quickly caught fire. Since then, about 120 cities have adopted laws that establish a wage floor, from $9 to $16 an hour, mostly for businesses that receive contracts or subsidies from local governments. Unions and community organizing groups – particularly ACORN – played key roles in mounting these campaigns.

The living wage movement was one of the most successful, if unheralded, community organizing efforts over the past two decades. By injecting the phrase “living wage” into the public debate, it helped shift public opinion, since it implicitly suggests that people who work full-time should not live in poverty.

Likewise, the Occupy Wall Street movement, which began in New York City in September 2011 and quickly spread to cities and towns around the country, change the national conversation. At kitchen tables, in coffee shops, in offices and factories, and in newsrooms, Americans began talking about economic inequality, corporate greed, and how America’s super rich have damaged our economy and our democracy. Occupy Wall Street provided Americans with a language – the “one percent” and the “99 percent” – to explain the nation’s widening economic divide, the super-rich’s undue political influence, and the damage triggered by Wall Street’s reckless behavior that crashed the economy and caused enormous suffering and hardship.

Even after local officials had pushed Occupy protestors out of parks and public spaces, the movement’s excitement and energy were soon harnessed and co-opted by labor unions, community organizers, and progressive politicians like Seattle’s Murray, New York’s de Blasio, newly-elected mayors Betsy Hodges of Minneapolis and Marty Walsh of Boston, and many others, who embraced the idea of using local government to address income inequality and low wages.

The proportion of American workers in unions has fallen to 11 percent — and to 6 percent in the private sector. Union activists view these campaigns among low-wage employees – disproportionately women, people of color, and immigrants – as a potential catalyst to rebuild the labor movement as a force for economic justice and as a way to regain public support.

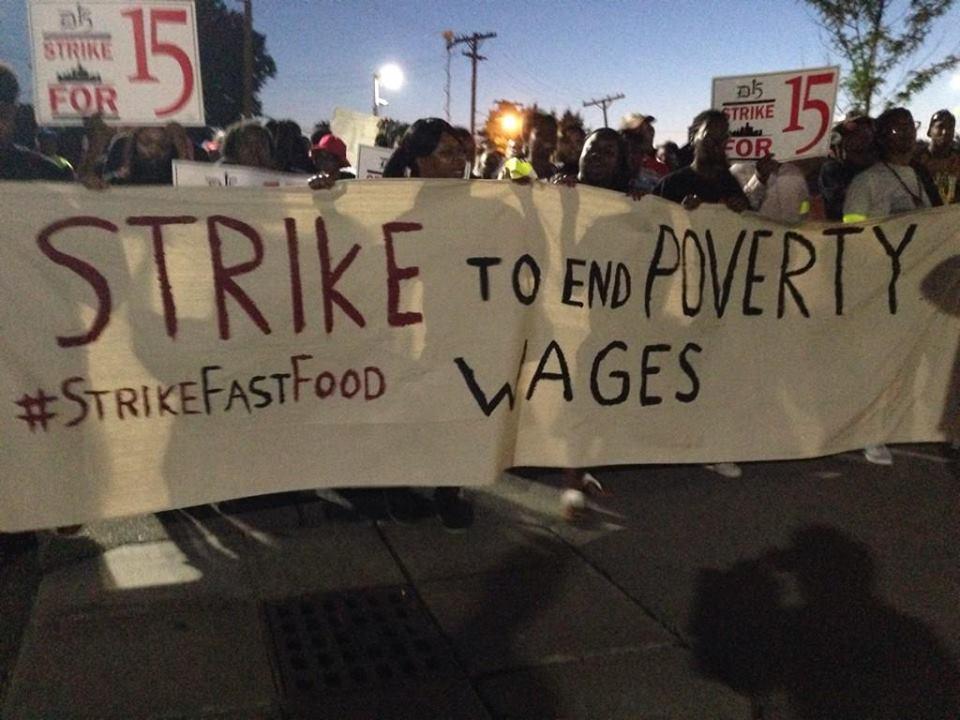

Growing activism by low-wage workers around the country – assisted primarily by SEIU, UNITE HERE, and the United Food and Commercial Workers union – has put a public face and sense of urgency over the plight of America’s working poor. Over the past two years, workers across the country at fast-food chains such as McDonalds, Taco Bell and Burger King have gone on strike and demanded a base wage of at least $15 per hour. Walmart workers have engaged in one-day work stoppages and civil disobedience as part of an escalating grassroots campaign to demand that the nation’s largest private employer pay its workers at least $25,000 a year, thousands more than a full-time worker making $10.10 per hour would earn.

These protests triggered increasing media coverage, including brilliant put-downs on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report of the conservative arguments against the minimum wage. Progressive think tanks have produced reports that gave substance to growing public outrage about the widening divide and the plight of the working poor. According to the National Employment Law Project (NELP), the majority of new jobs created since 2010 pay just $13.83 an hour or less. Last year a NELP study revealed that the low wages paid to employees of the 10 largest fast-food chains cost taxpayers an estimated $3.8 billion a year by forcing employees to rely on public assistance to afford food, health care, and other basic necessities. A study released in March by the Institute for Policy Studies found that the bonuses handed to 165,200 executives by Wall Street banks in 2013 – totaling $26.7 billion – in would be enough to more than double the pay for all 1,085,000 Americans who work full-time at the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

The reality of widening inequality and declining living standards, the activism of Occupy Wall Street radicals and low-wage workers, and increasing media coverage of these matters has changed public opinion. A national survey by the Pew Research Center conducted in January 2014 found that 60 percent of Americans – including 75 percent of Democrats, 60 percent of independents, and even 42 percent of Republicans – think that the economic system unfairly favors the wealthy. The poll discovered that 69 percent of Americans believe that the government should do “a lot” or “some” to reduce the gap between the rich and everyone else. Nearly all Democrats (93 percent) and large majorities of independents (83 percent) and Republicans (64 percent) said they favor government action to reduce poverty. Over half (54 percent) of Americans support raising taxes on the wealthy and corporations in order to expand programs for the poor, compared with one third (35 percent) who believe that lowering taxes on the wealthy to encourage investment and economic growth would be the more effective approach. Overall, 73 percent of the public – including 90 percent of Democrats, 71 percent of independents, and 53 percent of Republicans – favor raising the federal minimum wage from its current level of $7.25 an hour to $10.10 an hour.

Major business lobby groups routinely oppose raising the minimum wage at local, state and federal levels. But a new survey of business executives suggests that these trade associations may not be speaking for the majority of their members. In fact, a majority of business executives surveyed by CareerBuilder.com actually favor raising the minimum wage, saying it would raise the standard of living among their employees and give the companies a better chance to hold on to their workers. A whopping 62 percent of employers said the minimum wage in their state should be increased. A mere 8 percent of those surveyed said $7.25 an hour, the current federal minimum wage, is fair. The majority of employers, 58 percent, said a fair minimum wage is between $8 and $10 an hour, while others nearly 20 percent said a fair minimum wage is between $11 and $14. And another seven percent believed that minimum wage workers should make $15 or more per hour. (The study was based on a survey of 2,188 full-time hiring and human resource managers).

In other words, progressives have clearly won the moral argument. Americans believe that people who work should not live in poverty. So business groups have to resort to persuading the public that raising the federal minimum wage – or adopting a living wage or minimum wage plan at the local level – will hurt the economy. Business lobby groups and business-funded think tanks – including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and its local affiliates, the National Restaurant Association, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Employment Policies Institute (an advocacy group funded by the restaurant industry) and other industry trade associations – typically dust off studies by consultants-for-hire warning that firms employing low wage workers will be forced to close, hurting the very people the measure was designed to help.

But such dire predictions have never materialized. That’s because they’re bogus. In fact, many economic studies show that raising the minimum wage is good for business and the overall economy. Why? Because when low-wage workers have more money to spend, they spend it, almost entirely in the local community, on basic necessities like housing, food, clothing and transportation. When consumer demand grows, businesses thrive, earn more profits, and create more jobs. Economists call this the “multiplier effect.”

Moreover, most minimum-wage jobs are in “sticky” (immobile) industries – such as restaurants, hotels, hospitals and nursing homes and retail stores – that can’t flee.

In their new book, When Mandates Work: Raising Living Standards at the Local Level, economists Michael Reich and Ken Jacobs of the University of California at Berkley summarize the findings of research on the impact of local minimum wage laws. They discovered that there are no differences in employment levels between comparable cities with and without living wage laws. In doing so, they showed that business lobby groups are crying wolf when they claim that these laws drive away business and kill jobs.

All this local activism and shifts in public opinion have had a significant political impact. Mainstream politicians of both parties increasingly feel compelled to discuss the nation’s growing inequality and the greed of the super-rich.

In his January 2013 State of the Union address, Obama proposed raising the federal minimum wage to $9 an hour. “Even with the tax relief we’ve put in place, a family with two kids that earns the minimum wage still lives below the poverty line. That’s wrong,” Obama said. The following November, he embraced a bill sponsored by Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa and Rep. George Miller of California to lift the federal minimum to $10.10 an hour.

In the 2012 Republican presidential primaries, some GOP candidates attacked Mitt Romney for being an out-of-touch crony capitalist. In his campaign against Obama, Romney opposed a hike in the minimum wage. But this May Romney urged Republicans to endorse a $10.10 minimum wage, arguing that it would help GOP candidates “convince the people who are in the working population, particularly the Hispanic community, that our party will help them get better jobs and better wages.”

It is unlikely that either Obama’s or Romney’s change of heart was the result of key economic advisers persuading them that a bigger wage boost was needed to reduce poverty and stimulate the economy. Both of those things are true, and surely entered into their thinking, but the major impetus was political. They were responding to the growing protest movement, public opinion polls and election outcomes that reflect widespread sentiment that people who work full time shouldn’t be mired in poverty.

Despite public support for a federal wage hike, the Republicans in Congress have refused to budge. In March 2013, for example, all 227 House Republicans (plus six Democrats) voted against the Harkin-Miller bill. (184 Democrats voted yes). This year, Democrats, unions and other progressives view the growing momentum for a minimum-wage hike as a way to pressure Congressional Republicans facing tough re-election campaigns next year, hoping to persuade them to support an increase.

Whether they do or don’t, the movement to raise wages will continue to gain momentum at the local and state levels. It is a heartening reminder that democracy – the messy mix of forces that typically pits organized people versus organized money – can still work.

(This feature was crossposted at Huffington Post.)

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care

-

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 27, 2026Agents In ICE Shootings Made Racist or Sexist Remarks, Records Show

-

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026As Climate Crisis Upended Homeowners Insurance, the Industry Resisted Regulation