Environment

Energy Democracy in Alameda County: Greener, Cleaner. Or Is It?

Energy experts have their doubts about East Bay Community Energy’s ability to immediately deliver power that does not involve a hydroelectric dam — or even a smokestack.

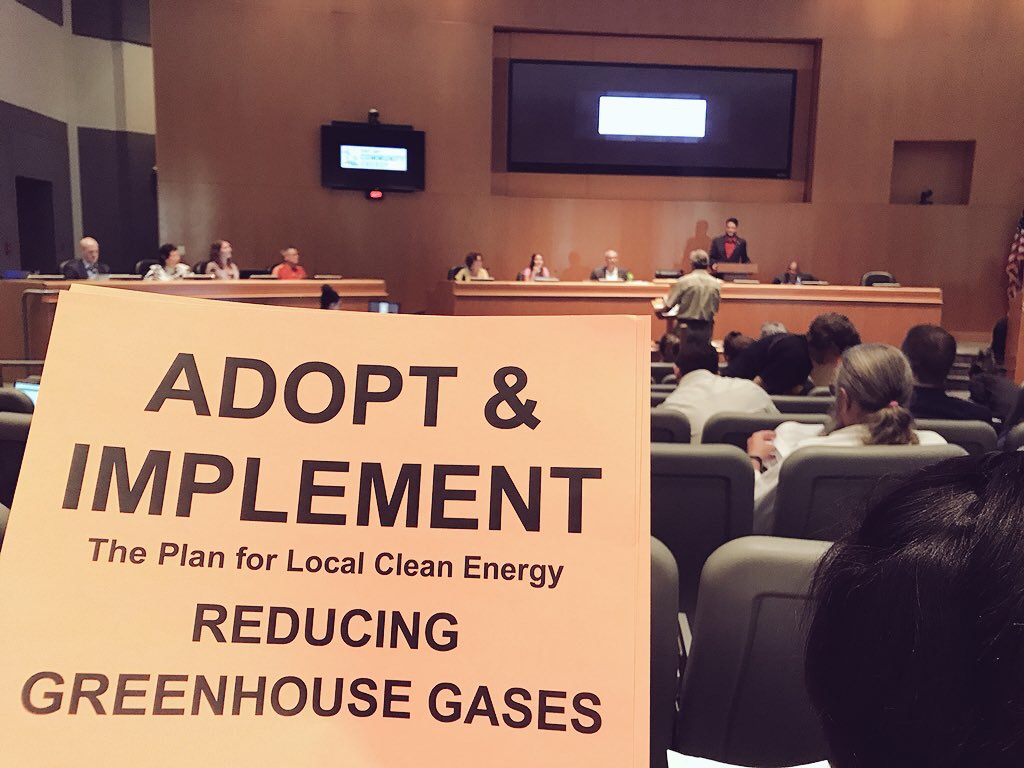

When, on July 18, a brand-new community energy venture unveiled its five-year business plan, advocates for clean energy and environmental justice touted it as a first-of-its-kind coup. East Bay Community Energy (EBCE), a coalition of 11 cities and unincorporated areas in Alameda County, came together last year to find potentially cleaner and cheaper electricity for its customers than their for-profit utility, PG&E, can supply. The group has also promised to nourish the local economy with good jobs tied to renewable energy development, harnessing the county’s abundant wind and solar resources to clean up the air.

But some experts who monitor California’s energy policies have their doubts about EBCE’s ability to deliver power that does not involve a (carbon-free but fish-killing) hydroelectric dam — or even a smokestack — at least in the near future. “The business plan is of little relevance,” says Matthew Freedman, staff attorney with The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a nonprofit that polices corporate utilities and advocates for ratepayers. “The proof is what they actually commit to buy.”

EBCE has come together under the aegis of a 2002 California law that granted local jurisdictions the right to procure their own power, as “community-choice aggregators,” or CCAs. The ideals of the CCA have always involved encouraging more clean energy generated locally, and offering it to consumers at competitive rates. For-profit utilities have been accused of delaying the transition from coal and natural gas to renewables, as well as starving local economies by importing power from out of state.

Yet even for the community energy groups, those ideals have been almost impossible to realize. Community power programs are opt-out — if you live in a place that has one, you’re automatically subscribed — but consumers can still defect if prices spike. Power suppliers have to stay competitive or die.

And some did die early on, victims of both organized campaigns by the large utilities, and a renewable energy landscape that wasn’t quite ready to meet their demands. Even after the price of solar cells began dropping in 2009, inciting a solar boom, labor unions still opposed CCAs on the grounds that the groups weren’t doing anything for new energy development — they were, instead, doing an end run around utilities to buy the same old dirty power. “At present, there is no pathway from a power purchase agreement with [traditional energy] companies to creating local jobs with union-scale wages and benefits,” read a statement from IBEW 1245 in 2013. (Disclosure: IBEW 1245 and the California Nurses Association are financial supporters of this website.)

East Bay activists were acutely aware of these factors when they started lobbying for a community choice program in the county. “One of our demands was not to use ‘renewable energy certificates,’” says Jessica Tovar, lead organizer with Oakland’s Local Clean Energy Alliance. Renewable energy certificates, or RECs, are green-labeled kilowatts sold on the electricity market independent of actual generation. Because they’re not investments in new renewable generation, RECs don’t spur the development of new wind and solar projects. (They might not even originate from renewable generation at all — on the mixed-up electricity market, you can’t tell a coal electron from a wind one.) “We emphasized from the beginning that we wanted to have actual local renewables produced in the county.”

That demand was part of the organization’s “unity position,” says Tovar, along with the Alameda Labor Council and the California Nurses Association. “Oftentimes the environmental and social justice movements don’t work together,” she says. “It was a big deal for us to be able to ask for those things, working together, at the time.”

EBCE, which has supplied electricity to non-residential consumers since June, and will begin serving residential customers in November, has agreed only to buy renewable energy certificates if they prove necessary to its financial health. It’s hard to know exactly what that means. Until the CCA has the credit rating and assets to sign long-term contracts for new projects with local energy developers, it will have to rely on electricity from existing facilities throughout the West. Such purchases often involve some kind of environmental trading mechanism that can disguise dirty energy as clean. One of EBCE’s options offers “carbon-free” power, which in this case, means power from large hydroelectric plants in the Pacific Northwest or Canada.

“The carbon-free angle is worse than meaningless,” Freedman says. “We’ve seen Northwest utilities that have abundant electricity supplies send a clean resource [to a CCA] and then backfill with a dirty resource to meet their existing demand.” The amount of hydroelectric in EBCE’s resource plan, Freedman says, “is staggering.”

Tovar isn’t happy with the carbon-free option either. “We know better and want to do better,” she says. Doing better just takes time.

Freedman doesn’t dispute that. “When a CCA starts up it needs to have a product to sell on day one,” he says. “New clean energy infrastructure takes time to design and implement.”

If all goes well, Tovar sees EBCE paving the way for other energy innovations, such as shared solar, solar cooperatives and microgrids — small, self-contained distribution networks that can interact with the grid or “island” and operate on their own in a crisis. She and other clean-energy advocates hope to see rooftop solar and battery storage become accessible to low-income households and renters, through shared and community projects made possible by the CCA.

Those are all towering asks, and Tovar is careful to note that none of them will become reality if energy decisions get made in a bubble. Consumers have to participate, too. “We call it energy democracy,” Tovar says. “It requires us all to play advocates for the kind of energy we want to produce.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.