Education

Living Homeless in California: For Many Kids, Home Is Where the School Is

The Los Angeles Unified School District has more homeless students than many school districts have in total enrollment. In response, the district has created some innovative policies.

For the teachers, counselors and school liaisons comprising the thin front line of educators grappling with the Golden State’s homeless student population explosion, the dire reality of what it means for the 268,699 young Californians public school districts identified last year as lacking “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” comes into grim focus during the home visit.

“I would find places where there was a garage [and] they would have an extension cord going to the front house,” Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) Homeless Education Program coordinator Angela Chandler told Capital & Main, recalling her time as a district counselor in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley. “The [floor] would be concrete with no carpet or anything, and there would be no real running water. The family would have to go to the front [house] to use the restroom.”

Also Read These Stories

In a city like Los Angeles, whose high poverty and low housing affordability edged out San Francisco for the stop spot on Forbes’ 2018 list of the worst American cities for renters, veterans like Chandler have long become accustomed to seeing two, three and even four families “doubled up” in apartments meant for one.

In 2016-2017, 80 percent of Los Angeles County’s 71,727 homeless-identified students checked “doubled-up” on the Student Residency Questionnaire for incoming public and charter school students mandated by the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act. The 1987 federal law, which first spelled out the education rights for the nation’s homeless students, requires all schools and districts to provide homeless students “equal access to the same free, appropriate public education, including a public preschool education, as provided to other children and youths.” The first step is to recognize them when they walk through the door.

But in California, where parents are already uncomfortable with a perceived social stigma around homelessness, the same climate of fear ushered in by Donald Trump that has already spooked immigrant families from using the country’s safety net, has introduced a new skittishness to being identified as homeless.

“We get phone calls from some schools, from our liaisons there, that parents are apprehensive,” Chandler explained. “[Parents] thought that it was tied to residency status instead of nighttime residency, like where you live.”

That apprehension could explain how when the official homeless head count for the city conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) soared 23 percent from the previous year, LAUSD’s homeless count dropped from 17,258 students in 2016-17 — to what Chandler said was a little over 15,000 in 2017-18.

Nevertheless, even that drop gives LAUSD more homeless students than many school districts have in total enrollment. Chandler serves them with an astonishingly skeletal staff: eight classified aides work the phones, coordinating the daily flood of district-wide calls for technical assistance and student supports; a sole “senior parent community facilitator” performs district-wide outreach; and the program’s heavy lifting falls to its 18 full-time counselors, who are charged with keeping the district’s homeless kids in the classroom and on track to escape the cycle of homelessness.

With homelessness, the clock is always ticking; the longer it lasts, the more dramatic its impact. Compared to non-homeless students, homeless kids become even more likely to be held back from grade to grade, to be chronically absent, to fail courses, have more disciplinary issues, and to drop out of high school. As with all extreme poverty, the traumas and deprivations of homelessness are just as toxic to early development and learning, to performance in middle and high school and to diverting kids into the juvenile justice system.

“Every time they change schools, they have setbacks,” Chandler said. “It’s harder for them to adjust. And we already know that their life is very chaotic, and some of it’s traumatic. So our focus is to minimize the amount of changes that these youth and children have to go through so that they at least have one stable, safe place to go on a daily basis, which is their school sites.”

Providing that safe place is why, Chandler said, so much of the program is focused on training school personnel and community partners. LAUSD requires each principal to designate a staff member as homeless liaison, who is responsible for meeting and assessing the needs of each homeless student in home visits. But that person must first be able to interpret federal guidelines for who is homeless. McKinney-Vento’s “fixed, regular and adequate” definition is much broader than the narrower, unsheltered street sense used by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and by homeless service providers.

To pay for that service, LAUSD, like all California school districts, has been more or less left to cobble together money from wherever it can. Much of it comes from federal Title I funding for disadvantaged students, with some state money funneled through California’s new Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Anything beyond that is up to Chandler’s grant-writing prowess.

Last month, for example, the latter landed the district a competitive, $250,000, three-year federal Education for Homeless Children and Youths Grant. Chandler’s ingenuity wrangled money for three additional program positions when she managed to piggyback onto a Los Angeles County Office of Education proposal for tapping dollars from Measure H, the quarter-percent sales tax passed by county voters in 2017 for homeless services and prevention.

But Chandler was also instrumental in developing the strategy that has proved to be a game-changer for the district — the coup of bureaucratic diplomacy that wed LAUSD’s Homeless Education Program with L.A. County’s new Coordinated Entry System (CES), the database created in 2010 putting the most vulnerable of the homeless population in the front of the available housing queue. Practically, it meant co-locating LAUSD staffers inside the homeless-services providers to help train and aid them in referrals by meeting with families as they came for their intake sessions.

“Prior to them being there, trying to negotiate where these kids went to school or keeping them in the same school was incredibly difficult, because we don’t speak the same language that the districts do necessarily,” said Kris Freed. She is the chief programs officer for L.A. Family Housing, which owns and operates affordable housing and permanent supportive housing in the San Fernando Valley. “[Now] they’re huddled with us, if you will, so they hear everything that’s happening and can engage at any point and say, ‘I can help. I can step in. I can do this.’ ”

Chandler’s dream for the program is to build it into something that looks a lot more like L.A.’s robustly funded foster care system. Administered through the county’s Department of Children and Family Services, foster care provides kids with full-time, dedicated advocates and greater access to resources like scholarships and tuition programs to get into universities and colleges. It even offers independent living programs, so once kids age out or time out of the system, they land in some type of stable housing.

“The way out of poverty is through education,” she said. “We want our youth to become self-sustaining, so they can go on to school or get a decent job and are not homeless adults.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Locked OutDecember 23, 2025

Locked OutDecember 23, 2025Section 8 Housing Assistance in Jeopardy From Proposed Cuts and Restrictions

-

Latest NewsDecember 22, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 22, 2025Trump’s War on ICE-Fearing Catholics

-

Column - State of InequalityDecember 24, 2025

Column - State of InequalityDecember 24, 2025Where Will Gov. Newsom’s Evolution on Health Care Leave Californians?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

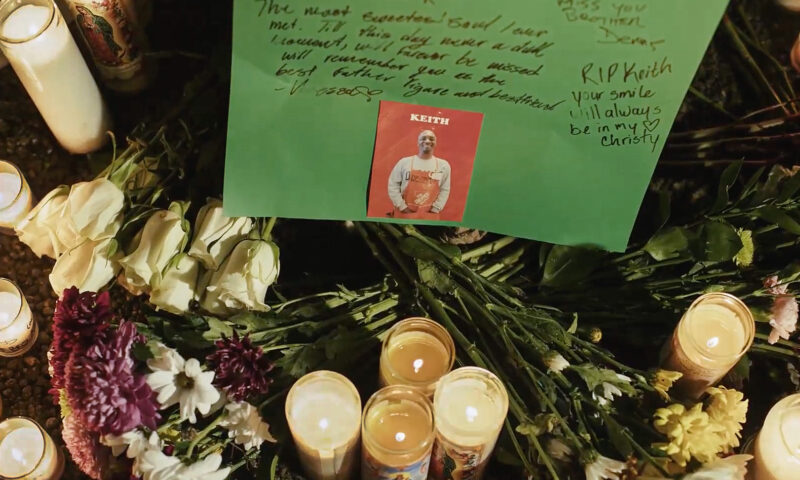

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025Editor’s Picks: Capital & Main’s Standout Stories of 2025

-

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025From Fire to ICE: The Year in Video

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?