Culture & Media

Stage Reviews: Three Provocative Broadway Dramas

Human frailty and societal faults are being vividly probed on Broadway as the season draws to a close.

Human frailty and societal faults are being vividly probed on Broadway as the season draws to a close. Tony-nominated and a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in drama, Stephen Karam’s The Humans, performing at the Helen Hayes, is the most talked about of these works, and rightly so, for it taps into the zeitgeist in uncommonly smart, touching and humorous ways – frequently simultaneously.

Set in a dilapidated, if spacious, apartment (designed with impressive verisimilitude by David Zinn) in New York’s Chinatown on Thanksgiving, the play unfolds in real time. Parents Erik and Deirdre Blake (Reed Birney and Jayne Houdyshell) have driven from Scranton, Pennsylvania – the playwright’s hometown – to visit their younger daughter, Brigid (Sarah Steele), who has just moved in with her boyfriend, Rich (Arian Moayed). Brigid’s older sister, Aimee (Cassie Beck), has also come for the holiday, as has Erik’s frail and demented mother, Fiona (Lauren Klein, in a largely silent role), who lives with Erik and Deirdre.

Karam writes with abundant wit; several of the play’s zingers elicit hearty laughs, as well as winces and gasps. He also writes with great economy: We learn much about this middle-class family’s current travails and its history during the show’s roughly 90-minute, intermission-less run time. The characters’ work-related complaints matter – the present economy doesn’t favor these folks, and there’s a clear suggestion that gender bias has contributed further impediments – but it’s the relentless tiny digs these obviously loving people can’t help themselves from making that provide the play’s most heartrending moments.

Deirdre struggles with her weight, Aimee with work and illness. Brigid isn’t getting anywhere as a composer, and even the seemingly stable Rich, soon to be a social worker, has had challenges in his past. And something is clearly eating at Erik, though only at the play’s end do we find out what. There’s a larger metaphor here, expressed mostly by the tension between these flawed yet ultimately decent people, but also by an inchoate, borderline supernatural apprehension, manifested in power failures (credit Justin Townsend’s lighting design) and slammed doors. This is Karam’s weakest gambit, but under the under the sure and subtle – and, yes, Tony-nominated – direction of the estimable Joe Mantello it hardly lessens the impact of this potent, disturbing, timely play.

Mantello has also directed the Tony-nominated revival of David Harrower’s gripping but manipulative Blackbird, a two-hander starring Jeff Daniels and Michelle Williams at the Belasco. The play, another without intermission, opens in media res, as Ray (Daniels) hauls Una (Williams) into an office break room. Their encounter is clearly awkward, but thanks to his purposely elliptical dialog Harrower keeps the source of the tension, and its profound implications, a tantalizing mystery until well into the drama. Along the way, we learn that Ray is troubled by Una’s sudden reappearance, that Una has something on Ray, and that these two haven’t seen each other in some time. Ultimately it’s revealed that Ray and Una had a physical relationship when he was over 40 and she was…12. But why Una has tracked down Ray (known in his present life as Peter), and why she cares so much about the details of his current situation remain frustratingly unexplored. More significant is Harrower’s stubborn insistence on detailing the sexual aspects of their repugnant bond through graphic description, when a more subtle approach would not only have been less rebarbative, but also more provocative.

As Ray, Daniels vacillates between panic and defiance, as Williams hovers on the verge of a breakdown, even as she clearly (and understandably) enjoys taunting Ray. The difference is that whereas Daniels disappears completely into his role in a nuanced performance that makes us both loathe and pity the character, Williams delights in a mannered, twitchy portrayal of Una. Mantello keeps what might have been static action almost constantly in flux, and Harrower offers one last twist as the play concludes on a distressingly ambiguous note.

Also up for a best-revival Tony is Ivo van Hove’s taut, harrowingly compelling reinvention of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, the second of this Belgian director’s thrilling reconceptions of a Miller play this season – the first was A View From the Bridge. (Both productions have earned a nomination for best revival of a play, as well as for Jan Versweyveld’s lighting design.)

Van Hove abandons preconceptions of what can be a preachy and predictable – to say nothing of prolix – play and in the process erases the prejudices that jaded audiences might bring. The virtues here are many, even if several of the boldest moves – modern dress, a classroom for a set, a mixture of accents and anachronistic multiracial casting – don’t sound as though they’d work with this material. Yet all these innovations succeed, including some aerial special effects and haunting choral background music. That’s because van Hove treads thoughtfully and respectfully, but also because – heaven help us – Miller’s McCarthy-era cri de coeur feels relevant again.

Those who (wrongly) fear a musty revival may come anyway thanks to the extraordinary company of actors assembled by van Hove. Miller requires 18 individual characters, irrespective of extras, and having two Oscar nominees (Saoirse Ronan and Sophie Okonedo) and a Tony winner (Jim Norton) among them counts as luxury casting. That’s to say nothing of seeing Ben Wishaw reinvent the central role of John Proctor and Ciarán Hinds practically spew sulfur as he walks the stage as Deputy Governor Danforth, the personification of bureaucratic evil.

Okonedo shines in her compassionate turn as Elizabeth Proctor, as does Ronan as Abigail, who defies and bullies her elders with chilling authority. And who would guess that 20-year-old Tavi Gevinson – still best known as a teen fashion blogger – could personify the conflicted Mary Warren with such touching vulnerability?

The list of effective portrayals continues: Bill Camp’s turn as the Reverend Hale, who nearly misses his chance to save his conscience; Jason Butler Harner’s craven, contemptible Reverend Parris; and Norton’s Giles Corey and Brenda Wehle’s Rebecca Nurse, who stand on the opposite side of the moral equation.

If Broadway is to be more than a place for tourists to enjoy expensive musicals, it must maintain its commitment to serious dramas like these – where important issues play out under gifted directors and companies of actors who can astonish audiences with their communicative powers.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

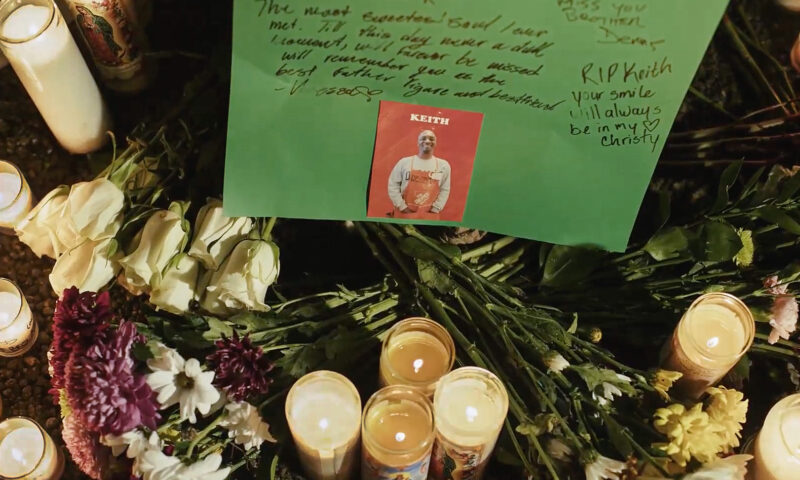

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026Can California’s New Immigrant Laws Help — and Hold Up in Court?

-

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026Keeping People With Their Pets Can Help L.A.’s Housing Crisis — and Mental Health

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated