Labor & Economy

Wealth Is Becoming Inherently Unfair

I have a friend who is intelligent, thoughtful and holds a responsible position in a major firm. From time to time we exchange ideas about the condition of American society, particularly how the economy shapes our democracy these days. We often agree about the dimensions of the problem, but disagree about what should be done about it. When it comes to the inheritance tax, we stand at opposite poles.

He thinks that what a person has accumulated in their lives is theirs to do with as they please, period. If they want to hide it offshore in the Virgin Islands, fine. If they want to give it all away, fine. And if they want to just pass it along to their children, no problem. As far as he is concerned the 400 who own as much as half the American population can do whatever they want – it’s their money.

I’ve always thought the opposite. If you own extreme wealth, it should be returned to the common good from which it was earned. Those who have benefited the most from this country should pay the most. After all, our national government provides security and stability as well as infrastructure – from power to roads to water to land – which makes economic development possible. Government also educates the work force that business needs to fulfill its goals. That’s the purpose of national life, it says so right there in the Preamble to the Constitution.

A high tax on the inheritance of extreme wealth also pushes the rich to a generosity beyond their usual behaviors. Recent studies have shown that the rich are less empathic, less compassionate, less “pro-social behavior” than the rest of us. A dozen sociological experiments looking at this issue have reached the same conclusion. Unless they are forced, the rich do not share well with others. So a high inheritance tax compels the rich to seek relief and keep their wealth intact. Over the years the tax man and the tax lawyers have worked out ways to do this – from trusts to foundations to charities. Without confiscatory taxes, little of this would happen.

We also know that dynastic wealth creates inequality. The French economist Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, has documented this across more than a century and beyond national boundaries. But he is not the only economist to notice this phenomenon. His colleague, University of California, Berkeley professor Emmanuel Saez, has determined that in the first three years of recovery from this latest recession, 95 percent of the wealth went to the top one percent. The growth of wealth outpaced the growth of jobs and income from work. So wealth passed from one generation to the next will mean more inequality between the very rich and the rest of us.

Piketty and Saez are not the first Frenchmen to suggest that this is not healthy for democracy. Alexis de Tocqueville, scion of a French noble family, visited America in the 1830s and traveled up and down the Eastern seaboard, as well as inland to the Mississippi River, observing how the new experiment of self-government was working. In his landmark book Democracy in America, a text still studied in political science classes and read and quoted widely, he argued that aristocracy diminishes democracy. De Tocqueville marveled at the ability of ordinary Americans to come together to define a problem, agree on a solution and carry it out – something unknown in his home country, where every proposed action of regular people had to be vetted by the nobility before even volunteers could do anything to change a situation.

De Tocqueville concluded that Americans would always have this power because they had broken the capacity of the wealthy to pass on their accumulated riches intact to the next set of progeny, therefore undermining the formation of an aristocratic class. The inheritance tax was a tool that kept democracy participatory.

Except, not so much anymore. Congress has cut tax rates and increased the threshold for assets subject to the tax. Meanwhile a rich elite continually lobbies for the abolition of inheritance taxes altogether, even though only one half percent of estates pay anything! That’s less than two people out of every 1,000. This backdoor effort to impose an aristocracy bodes ill for the American republic.

But my friend doesn’t see it that way. As he concluded, “That’s what I think.” But “think” is the wrong word here. He holds a belief that none of the evidence supports. Neither facts nor philosophy. And, frankly, I am alarmed, because he is not alone in this position, while the voices of the one percent and the people who believe in them grow louder.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

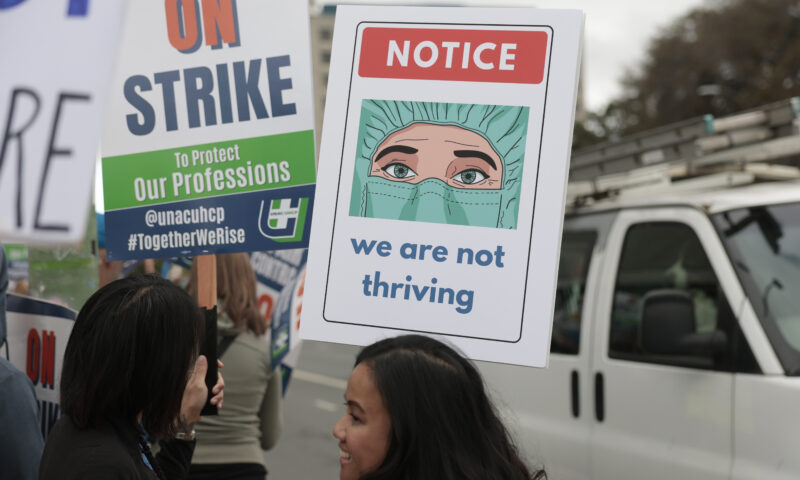

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive