Days after starting his second term, President Donald Trump issued a series of executive orders that targeted DEI programs and policies for elimination, decrying them as illegal and immoral. Museums across the country scrambled to react — and in many cases, comply. Within days, Washington’s National Gallery of Art announced it would close its office of belonging and inclusion and remove the words “diversity, equity, access and inclusion” from its list of values on its website. Five days later, the Smithsonian followed suit.

But the Japanese American National Museum, a relatively small institution in downtown Los Angeles, chose a different path. Founded in 1992 at the site of a historic Buddhist temple in L.A.’s Little Tokyo, the museum took a stand against Trump and his anti-DEI edicts while other museums acquiesced. Two weeks after the Smithsonian shuttered its DEI office and stripped its websites of DEI-related language, JANM’s leaders announced that they would not waver from their commitment to DEI or their mission of telling the full truth about the Japanese American experience, World War II incarceration camps and all. We will scrub nothing, JANM announced, in what would become a slogan for the museum’s defiance. That stance came with significant risks: At stake were millions in federal grants from institutions like the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

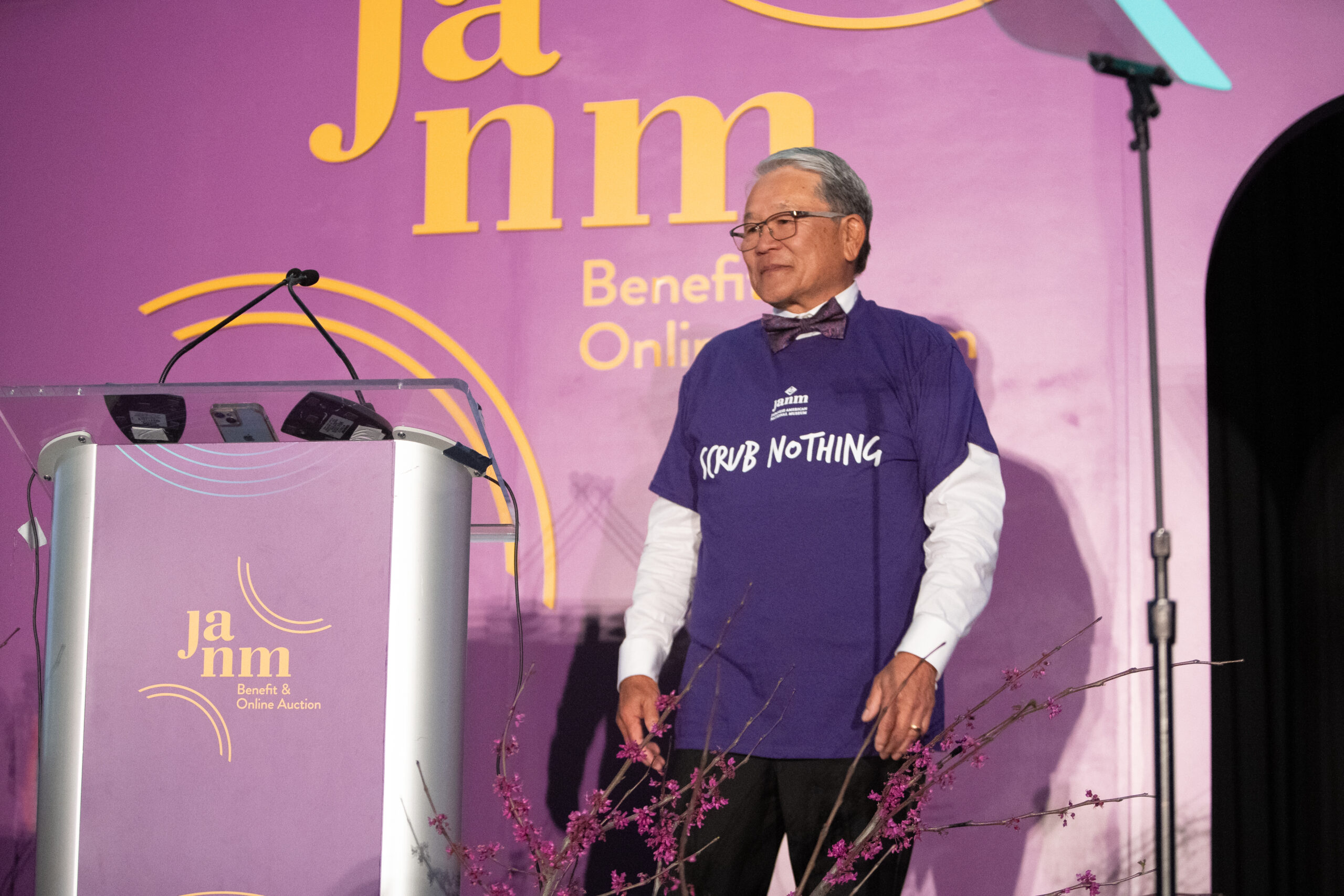

“You can’t put a price tag on your community’s integrity and your institution’s integrity,” said William T. Fujioka, chair of JANM’s board of trustees and the former chief executive officer of L.A. County.

William T. Fujioka at the JANM Benefit and Online Auction event in April. Photo: Tracy Kumono.

To date, JANM, which has an operating budget of around $13 million, has lost $660,000 in federal funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, said Sherrill Ingalls, JANM’s director of marketing and communications. In October, the museum was also turned down for a Japanese American Confinement Sites grant from the National Park Service that funds projects about the Japanese American incarceration camps — a story central to the museum’s existence since it was founded.

“We always got money for this grant,” Fujioka said. This year: nothing.

“I don’t think we can draw conclusions,” said Ann Burroughs, JANM’s President and CEO. “I think it’s important that you quote that: We can’t draw conclusions.”

“But one hears things anecdotally,” she added.

“We don’t know for a fact why we didn’t get it,” Fujioka said. “But it’s probably grounded on the very vocal and strong position we’ve taken.”

Sticking to your principles in defiance of a vindictive president and your own financial interests is never easy. But as many prominent museums — institutions whose primary mission is to inform the public about our collective histories — bend to Trump’s will, it’s become a stand few museums other than JANM have been willing to take.

“If you find some, let me know, because I haven’t seen it,” said Lori Fogarty, the director of the Oakland Museum of California. “And I’ve been actively looking to see what other museums might take the stance of bravery that JANM has taken.”

* * *

JANM’s decision to take a stand came at a board of trustees meeting last February. “We started to hear that other nonprofits, particularly other museums, were starting to scrub their websites of any references to DEI because they were afraid they were going to lose funding,” Fujioka said.

“The executive orders were coming fast and furious, and there was this pervasive fear of, ‘What the hell does this mean?’” Burroughs said. The trustees considered what might be lost by opposing the executive orders — both in terms of funding, but also by placing a very visible target on their backs. “We talked about the importance of standing up and being vocal,” Fujioka said.

In the end, the board voted unanimously to push back against Trump’s attacks on DEI, approving a strongly worded statement that called out the administration’s “attempt at erasure” and affirmed the museum’s commitment “to stand up for the truth about history” to fight discrimination and hate “and to ensure that no community is ever again subjected to the injustices that Japanese Americans faced.” “There were no dissenting voices,” Burroughs said.

“Nobody stood up for Japanese Americans in 1942, other than the Quakers and perhaps one chapter of the ACLU,” said Burroughs, who was jailed as a young activist in her native South Africa for her opposition to apartheid, and is also the chair of the board of directors of Amnesty International USA. “I think our trustees, the children of camp survivors, felt that weight of history enormously. Now was the time to stand up for other people and other communities that were under attack.”

Ann Burroughs speaks at the National Day of Action event at the Japanese American National Museum in August. Photo courtey JANM.

JANM’s statement was as thorough as it was bold, as the board decried the “erosion of civil rights” and the resurfacing of “racism, xenophobia, and authoritarianism” under the second Trump administration. It denounced Trump’s directive to build a migrant detention center at Guantanamo Bay; his invoking of the Alien Enemies Act to carry out mass deportations without due process (as was done to Japanese Americans during World War II); the administration’s attacks on birthright citizenship, among other actions.

“I was impressed,” Fogarty said of the statement, which was released on Feb. 11. “But it totally made sense to me, knowing JANM’s history.”

It’s the kind of stance that JANM has been taking for years. After 9/11, the museum’s leaders declared their solidarity with Muslim Americans, noting the similarities between the hysteria and hateful political climates of 2001 and 1942. “The Japanese American community came to Michigan to hold one of their conventions and to support the Arab American community here,” said Devon Akmon, former director of the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. “JANM was very instrumental throughout our early years.”

In 2017, JANM was among the first museums in the country to see its leaders speak out against Trump’s anti-Muslim travel bans, as the museum drew hundreds of people to a series of marches, vigils and rallies in support of the Muslim community. Over the years, the museum has held programs about everything from implicit bias to antisemitism at its National Center for the Preservation of Democracy.

The issue came to a head in April, when JANM learned that the Department of Government Efficiency had terminated a National Endowment for the Humanities grant that was to fund an annual program that brings teachers from across the U.S. to Little Tokyo to learn about the history of the incarceration camps. The central goal of the program was to prevent history from repeating itself by educating teachers about the camps who would then pass along that knowledge to their students.

The museum responded with a rebuke of the executive order Trump issued in March, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” “The order,” the museum said in an April 3 statement, “aims to replace nonpartisan, research-based, and comprehensive history of the US with a grandiose and simplistic narrative that omits the nation’s injustices, mistakes, and dark chapters.”

“The attack on DEI was anathema to us, because our mission is absolutely centered in a celebration of the ethnic and cultural diversity of the U.S.,” Burroughs said.

* * *

Word of JANM’s stand spread through museum publications, on social media and via arts blogs, local news outlets and the Japanese American ethnic press. And when Gov. Gavin Newsom was looking for an appropriate place to hold a press conference about Proposition 50 and congressional redistricting in August, he chose the museum’s National Center for the Preservation of Democracy. The spot is steps from the site where, in 1942, Japanese Americans assembled to board buses bound for American detention centers and incarceration camps. As Newsom made his remarks, dozens of masked and armed Border Patrol agents roamed around the center’s plaza, ostensibly to conduct an immigration raid. At the press conference, Newsom called those actions “sick and pathetic.”

U.S. Border Patrol agents march outside the Japanese American National Museum after a show of force during a Gavin Newsom press conference in August. Photo: Carlin Stiehl/ Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Since then, some other museums have also opposed Trump’s executive orders, though in quieter ways. A few, like JANM, are also choosing to “scrub nothing,” a message that JANM placed on t-shirts to raise money to replace lost federal funds. For JANM, scrubbing was never really a choice. What would a JANM exhibit or website look like without DEI? “It would be blank,” Burroughs said.

“Right now, a lot of museums are still trying to figure out how to navigate this very carefully and deliberately,” Akmon said. “I’ve had conversations with people who are very, very nervous about making public statements because of concerns like, ‘How do I shield my staff? How do we not get obliterated?’”

“I think it’s really important to acknowledge that not all museums have the same latitude to be as bold as JANM,” Akmon added. “There are factors like governance structures, funding, political environments, community pressures. But I do think that courage looks different in different contexts. For some it might be public statements and very forward-facing initiatives. For others, it could be quietly sustaining inclusive practices despite external pressure.”

Although San Diego’s Museum of Us isn’t taking a formal stance on DEI like JANM did, its current exhibit, which opened this November, is about as aggressively DEI in nature and name as one gets. Titled “Race: Power, Resistance & Change,” the exhibit “tells the truth about racial oppression and white supremacy in the Californias, and how indigenous and other communities of color have resisted that oppression,” said Micah Parzen, the museum’s CEO.

The exhibit was in the works years before Trump’s election to a second term, so it is “not a reaction [to the executive orders] by any stretch of the imagination,” he said. “We’re just continuing to do what we believe museums should be doing.”

At JANM, the museum is expanding the reach of its message beyond its Los Angeles walls with JANM on the Go, an ambitious outreach project undertaken this year while the museum’s main exhibit space is undergoing major renovations. The program is partnering with other museums and art institutions to present shows about Japanese American female artists in Philadelphia and Monterey, Calif.; exhibits about the incarceration camps in Chicago and Seattle; a showcase of Japanese American car culture in Pasadena; and film screenings of JANM-produced documentaries in theaters from Santa Monica to Nagoya, Japan. Burroughs can’t say how much of this collaboration with other museums has been driven by their stance on DEI. “But certainly there is more interest in our work,” she said.

Still others are simply choosing not to accept or apply for federal grants. Last October, the executive committee of the Oakland Museum of California, which focuses on the arts, history and culture, turned down a major grant administered by the Department of Interior after the department told the Oakland Museum executive committee that accepting the award would essentially affirm that the museum would abide by Trump’s executive orders against DEI. The museum also decided to stop pursuing federal grants in the future. “We wouldn’t be able to accept federal funding in good conscience with those strings attached,” Fogarty said.

Parzen isn’t applying for any new federal grants either. “We know, just from a practical perspective, we’re not going to get them,” he said. “Because the mandate is to not fund the so-called ‘woke’ museums.”

Parzen said the administration’s anti-DEI stance has completely upended what the grants were originally intended to do — and nearly guaranteed that places like JANM won’t get the sorts of grants they did in the past, like the National Park Service one they lost. “One of the key criteria they used to use to evaluate these grants was: Does it support a community of color that typically hasn’t been represented in museums?” Parzen said. “Whereas now, all of a sudden, it’s: Does the grant support the administration and celebrate patriotism and all the wonderful things about what it means to be American?”

Since the beginning of the year, the National Endowment for the Humanities has canceled at least 1,200 grants — an estimated 85% of its existing grants. It’s hard to quantify how much has been lost to federal cuts, both in terms of research and public-facing programs, but it’s a lot, say museum directors like Fogarty. “Those grants are really important because they are peer reviewed and so competitive that in order to receive one, it really has to be a model project,” she said. “So these grants would really jump-start very important projects.”

* * *

This March, Burroughs will be attending the California Association of Museums annual conference being held in Los Angeles in 2026. With museum leaders and administrators in attendance from across the state, Burroughs will likely field questions about JANM’s ongoing stance against the Trump administration — how it came to make it, and what it has cost them.

Why was JANM able to take such a strong stance against DEI, for instance, when so many others could not, or would not? A major factor was its board, which was the driving force behind JANM’s position, Fujioka said.

“There was no politics in that discussion,” Fujioka said. “What we talked about was our heritage, and our responsibility to the Issei and Nisei [first and second Japanese American] generations, who lost so much.”

For many museums, this is not typical. “Boards in particular are getting skittish and nervous and saying, ‘Maybe we need to change this a little bit,’” Parzen said. “‘We wouldn’t want to be on the radar and subject to an investigation or an audit.’”

JANM also has the advantage of being a culturally specific museum whose very existence is rooted in community activism. The museum was established because other museums across the country were not telling the history of Japanese Americans, and was funded, in large part, by individual Japanese American community members and groups. “I think a museum like the Japanese American National Museum, or even the Arab American National Museum, a lot of these culturally specific museums have a lot of clarity on why they exist,” Akmon said. “I mean, a deep, deep purpose. Being a museum is almost secondary. It’s like, we’re a museum because of this. That is a powerful proposition.”

“And sometimes, in some of the darkest hours,” he continued, “being bold, for these types of institutions, actually galvanizes their community.”

Ironically, JANM is, in many ways, in the same position as other museums that scrubbed their websites or canceled exhibits or chose not to take a stand. Even after the Smithsonian scrubbed its site, Trump announced an extensive review of the museum to ensure that it “reflect(s) the unity, progress and enduring values that define the American story”; similarly, in May, Trump called for the removal of Kim Sajet, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, because of her support of DEI, even after the gallery removed the DEI messaging from its website (she resigned the following month).

“A lot of museums chose not to speak out because they were afraid of funding getting cut,” Burroughs said. “Well, it’s been cut. It’s gone.”

For Burroughs, museums are at a critical crossroads where they must make tough decisions about how to stand up for their principles. “I just don’t believe for a second that museums can be neutral,” she said. “Museums can’t be neutral, whether you’re a science museum or an art museum or a cultural history museum. Especially at a time like this, when truth is under attack, when truth and history and science and art and culture is under attack, I think that we have a responsibility to stay firm.”

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026