Culture & Media

Remembering Walter Wink: Ethical Thought behind Non-Violence

“More deeply still, nonviolence is a spiritual challenge of epic proportions. It calls upon the soul’s authentic longing for heroism, for risking one’s life for an infinite stake, for self-transcendence in giving oneself to another.” – Walter Wink

After Reinhold Niebuhr succumbed to Cold War fever, there was no longer a major voice in Christian ethics among Protestants. In seminary, I myself had to read Paul Ramsey, who couldn’t get any closer to examining the ethics of war than resuscitating Just War Theory from the late days of the Roman Empire. Most of us who opposed the Vietnam War were stuck with a rationale that this-war-in-particular was unjust and therefore should be stopped. Since no one could articulate a thorough critique from a non-violent perspective, we were flying by the seats of our intellectual pants.

Little did I know that alongside mainstream Christian ethics, hidden somewhere in the obscure hallways of academia, a new voice was rising. When I finally stumbled across him in the early 1990s, I couldn’t get enough. Walter Wink, who died last month, gave me a new way to link ethical reflection to the action-oriented work that I had been part of even as I previously lacked an intellectual platform to build on. His three-volume work – “Naming the Powers,” “Unmasking the Powers,” and “Engaging the Powers” – filled in all the blanks, confirming the necessity of active non-violent action as the only effective tool for lasting, just social change.

Both Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cesar Chavez had been helpful, but I needed something beyond ad hoc, action-based philosophy of non-violence. I was looking for someone to provide an underpinning of a Western, theologically grounded understanding of non-violence as a way of life and a path of social change. Wink did that where Gene Sharp and Gandhi didn’t.

Part of the attraction was his ability to interpret the problem texts of the New Testament by placing the early Christian writers in the context of Roman imperialism so clearly that their punch couldn’t be missed. Rome and its empire were the exact opposite of what Jesus was doing. Wink also differentiated the early writers from the later authors who wrote at a time when Christianity had become the religion of the empire and defending “authority” without critique had become the norm.

Wink not only used eye-opening biblical analysis, he tapped Jung’s understanding of mythology to strip away the ways we middle-class Americans boosted ideas like love-of- country and the pursuit-of-affluence over the deep connectedness of all of life. Wink saw that the exterior forms of these loyalties were connected to the interior felt-life of individuals, institutions and nations. Corporations and countries not only acted in the visible realm of economics or world politics, they embodied an ethos, a zeitgeist, a spirit that roamed those realms as well. These powers, unchecked, would run rampant over people and communities, bring down entire economies, destroy whole nations, and obliterate tribes and languages and even species.

Wink was an ethicist who saw the big picture and did not shrink from it. Today I cannot read Bill McKibben or Chris Hedges without seeing Wink’s words and ideas. They are translated into the edge of our own issues, whether they are the integrity of the environment, the futility of Pax Americana or the fragility of the world economy. Wink ripped open power and made me see my own urges as the mirror image of the forces I intended to destroy. He made me see my own hubris and my own perfectionism as the seeds of destruction of my own efforts at change in the world.

Wink was never more persistent than in his belief – core to any non-violent change – that individuals and institutions, even nations, are redeemable. He held out for a world that was a “domination-free order characterized by partnership, interdependence, equality of opportunity and mutual respect” from the inside out.

Walter Wink, we will miss you. We will miss your voice. But as they say in the Spanish language tradition, Presente!

“The goal of civil disobedience and nonviolent direct action is to establish a political culture in which conflicts are managed without violence. the worldwide rush toward democracy is itself an indication that nonviolence is the human future.”

-

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025

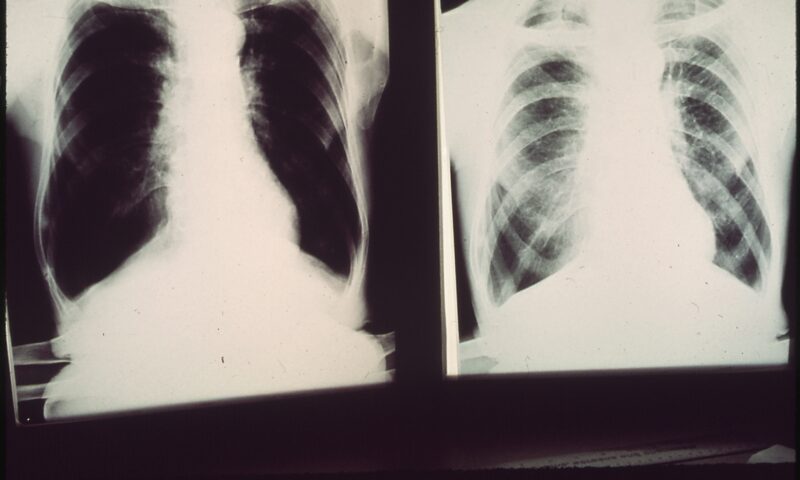

Latest NewsJune 17, 2025A Coal Miner’s Daughter Takes on DOGE to Protect Miners’ Health

-

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025

Beyond the BorderJune 10, 2025Detained Man Says ICE Isn’t Treating His Colon Cancer

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 5, 2025Budget Cuts Threaten In-Home Assistance Workers and Medi-Cal Recipients

-

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025

Column - State of InequalityJune 12, 2025‘Patients Will Suffer. Patients Will Die.’ Why California’s Rural Hospitals Are Flatlining.

-

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025

Column - California UncoveredJune 18, 2025Can Gov. Gavin Newsom Make Californians Healthier?

-

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025

Featured VideoJune 10, 2025Police Violently Crack Down on L.A. Protests

-

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025

Latest NewsJune 4, 2025Grace Under Fire: Transgender Student Athlete AB Hernandez’s Winning Weekend

-

Striking BackJune 3, 2025

Striking BackJune 3, 2025In Georgia, Trump Is Upending Successful Pro-Worker Reforms