California Expose

Paradise Burned: How Climate Change Is Scorching California

Paul Duncan, a battalion chief with California’s state firefighting agency, was at home in Northern California enjoying a day off on September 12 when he got the message: A wildfire was burning on Cobb Mountain, about a dozen miles away from Hidden Valley Lake, where he lived with his wife and two daughters.

Duncan, 46, decided to leave and help knock down the blaze because he knew the fire unit in the area was already short-staffed from putting out on another conflagration. Besides, his nearly 30 years of experience persuaded him there was no way a fire burning on a mountain to the west could burn down to the valley floor and then race eastward to threaten the Duncans’ home.

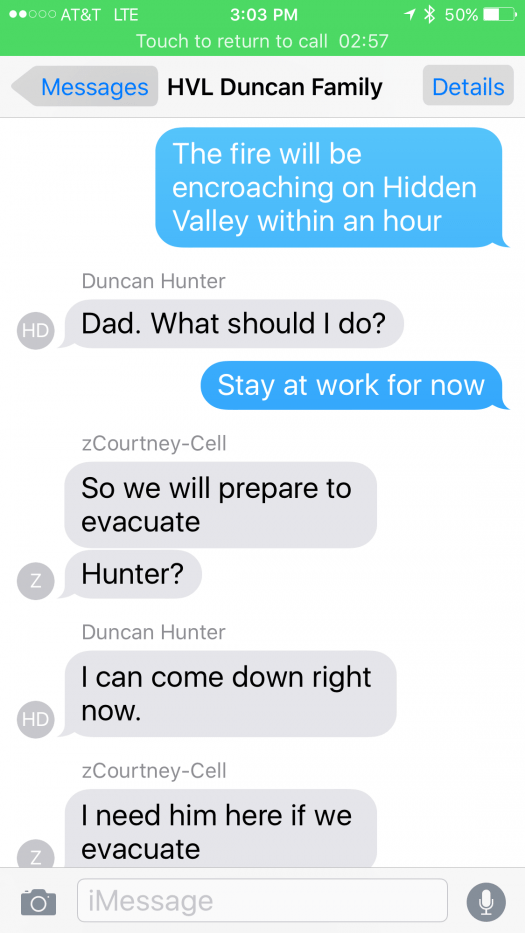

His optimism was short lived. Upon arriving on Cobb Mountain Duncan got some troubling news. The fire he was fighting was heading toward his family. At 5:13 p.m. he texted them: “The fire will be encroaching on Hidden Valley within an hour.”

Six minutes later his house was on fire.

Also Read: Young XL Pipeline Activists and the Long Haul

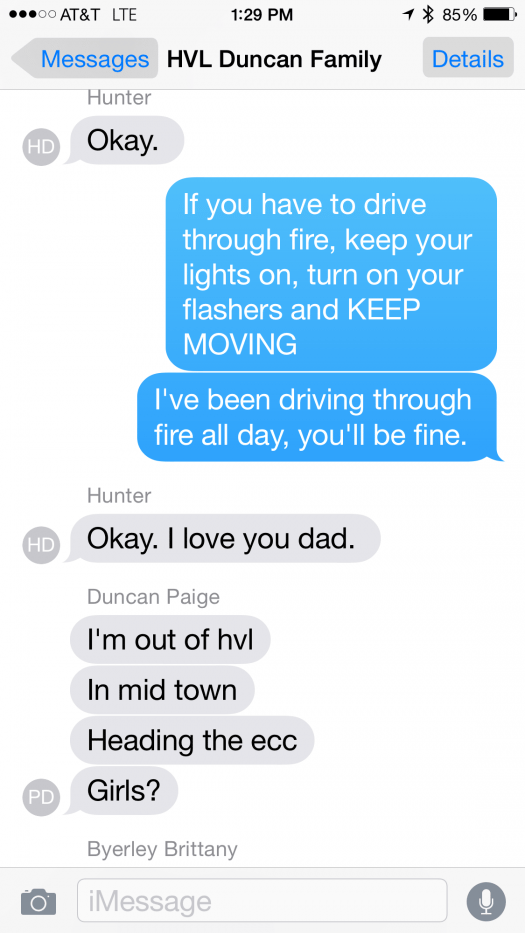

His family escaped safely, but they were later faced with having to drive through fire on the roads. At 6:37 p.m., Duncan texted a message to his family he never imagined he’d have to send.

“If you have to drive through fire, keep your lights on, turn on your flashers and KEEP MOVING.”

Ten minutes later, his wife, Courtney, called in a panic — there was too much fire to drive through. Duncan reassured her and told her to “step on the gas and drive through the fire.”

“This was a ferocious fire, wind-driven in brush, moving about 25 to 30 miles per hour,” Duncan would later tell Capital & Main, after his house had burned to the ground. “I’ve never seen this type of fire behavior, especially this far north in California. It came with a speed more like a Santa Ana fire in Southern California.”

The September inferno was dubbed the Valley Fire and it killed four people, destroyed 1,958 homes and other structures, and caused $1.5 billion in damages. Its name would join a lengthening roster of mega-blazes with names like Witch Fire, Station Fire, Rim Fire and Butte Fire. For firefighters these represent a new kind of fire that is devastating California and other states west of the Rockies. To climate and environmental scientists, they are evidence that global warming is creating a new and vastly expanded fire danger to the West.

See Wildfire Infographic

(Courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists)

[starlist]

California is facing the gravest threat to its natural beauty on record but many of us view the state’s expanded fire season as a cyclical anomaly – a belief sometimes spread by the mainstream media. A recent Los Angeles Times feature, provocatively headlined, “Gov. Brown’s link between climate change and wildfires is unsupported, fire experts say,” appeared to suggest that Governor Jerry Brown’s linkage of climate change to wildfires was politically motivated and had no basis in science. The Times story and some of its expert sources were quickly attacked by scientists and the watchdog group Media Matters for America, but the damage had been done by planting doubt in the minds of the newspaper’s readers.

Despite the Times’ inference that global warming plays a limited role in wildfires, the science is in and the picture it paints is ominous:

[/starlist]

- California is now losing nearly 90,000 acres a year (equivalent to the size of Las Vegas) to wildfires that have been increasing in size since 1984, according to Geophysical Research Letters.

- A report published in Ecological Applications concludes that 64 percent of the fire area burned by wildfires on public lands in the Western United States can be directly related to climate variables such as temperature, precipitation and drought.

- According to a Union of Concerned Scientists report, the annual number of large wildfires on federally managed lands in the 11 contiguous Western states has increased by more than 75 percent – from about 140 large fires during the period from 1980 to 1989, to 250 large fires between 2000 and 2009.

Max Moritz, a University of California, Berkeley environmental scientist who has studied wildfires for decades, tells Capital & Main, “Climate change is taking its toll. There is a likely link between climate change and the sizes and spread rates of this year’s wildfires.”

There are still doubters, however. Dismissing what he called “climate alarmism,” David South, a retired emeritus professor of forestry at Auburn University, told a U.S. Senate Subcommittee last year that the conclusion that global warming has caused more wildfires is simply wrong. He added in an email to Capital & Main that “the average area of wildfires burned during the 1930s was much higher than the average for the first decade of the 21st century . . .This does not support the hypothesis that carbon emissions have increased the area of wildfires annually.”

Nevertheless, those who fight wildfires on the ground say there has been a dramatic change in California’s fire behavior over the past decades.

“The fires are hotter, the fires are burning faster and they are consuming anything in their paths,” says Mike Lopez, who has been battling fires since the early 1990s and is now president of Cal Fire Local 2881, a union representing more than 6,000 firefighters. Adds Kim Zagaris, fire and rescue chief at the California Office of Emergency Services: “We are seeing longer fire seasons than I’ve seen in my 38 years.”

Again, the science backs up the firefighters’ observations. Last year’s Geophysical Research Letters study implicated “climate change as a prominent driver of changing fire activity in the Western U.S.,” and concluded that such wildfires have been getting bigger and more frequent over the last 30 years. This development is likely to continue as climate change causes temperatures to rise and droughts to become more severe.

By virtually all accounts the length of the wildfire season in California and the Western United States has grown. According to a report by Climate Central, an organization that studies changing climate and its impacts, the Western wildfire season has grown from five months on average in the 1970s to seven months today. During those years temperatures for spring and summer have risen and, Climate Central reports, mountain snowpacks are melting earlier, which leaves forests drier for longer periods of time.

Scientists and research studies also point to related problems, such as the fact that the warmer temperatures contribute to beetle infestations that, in turn, cause trees to die and potentially cause wildfires to burn more quickly. The U.S. Forest Service, for instance, says that from 2000 to 2013, bark beetles killed 47.6 million acres of forests in the Western United States—an area roughly the size of Nebraska. The warmer temperatures have allowed the beetles to survive longer and reproduce more, resulting in record epidemics. They are now able to infect higher-elevation pine trees. In California alone, an estimated 12.5 million trees have died during the drought, with many of the deaths attributed to beetle infestations.

Paul Duncan says he believes that pine trees killed by beetles likely helped contribute to the rapid spread of the fire that destroyed his home.

The economic consequences of the recent wildfires have clearly been catastrophic.

In its “Global Catastrophe Recap,” reinsurance broker Aon Benfield of London detailed the human and property losses of that and other recent California wildfires.

“Multiple wildfires raged across California during much of September, with the Valley Fire, northwest of San Francisco, and the Butte Fire, southeast of Sacramento, the most destructive of the fires,” the study stated. The Butte Fire erupted in the Sierra Foothills September 8 and left two people dead, while causing an estimated $450 million in damage.

This year’s California wildfires are part of a worldwide phenomenon. The Aon Benfield report notes, for instance, that “Wildfires continued to burn in Indonesia’s Sumatra and Kalimantan regions as the worst year for wildfires since 1997,” causing an estimated $4 billion in losses in terms of lost agriculture production, destruction of forest lands, health, transportation, tourism and other economic endeavors.

Scientists, firefighters, economists and government officials caution that the wildfires are likely to worsen. “The threat of wildfires is projected to worsen over time as rising temperatures – rising more rapidly in the American West than the global average – continue to lead to more frequent, large and severe wildfires and longer fire seasons,” states the Union of Concerned Scientists’ report.

The report also points out that the large wildfires have serious impacts on health and the economy that are often overlooked or underestimated. Smoke from wildfires carries small particles of soot that can enter the lungs and result in serious health problems. Young children, the elderly and people with asthma and other respiratory problems are at the most risk.

“We are in a different fire regime,” says Rachel Cleetus, lead economist and climate policy manager with the Union of Concerned Scientists, and co-author of the group’s 2014 study. “If we do nothing, we’re going to see wildfire season get worse and worse, get more costly and get more dangerous.” She says that the situation affects all of the Western United States, but is most urgent in California.

“It’s in the bulls-eye of the risk,” Cleetus says.

(Valley Fire photo credits: Top and homepage images by Jeff Zimmerman/Emergency Photographers Network.)

-

StrandedNovember 25, 2025

StrandedNovember 25, 2025‘I’m Lost in This Country’: Non-Mexicans Living Undocumented After Deportation to Mexico

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025

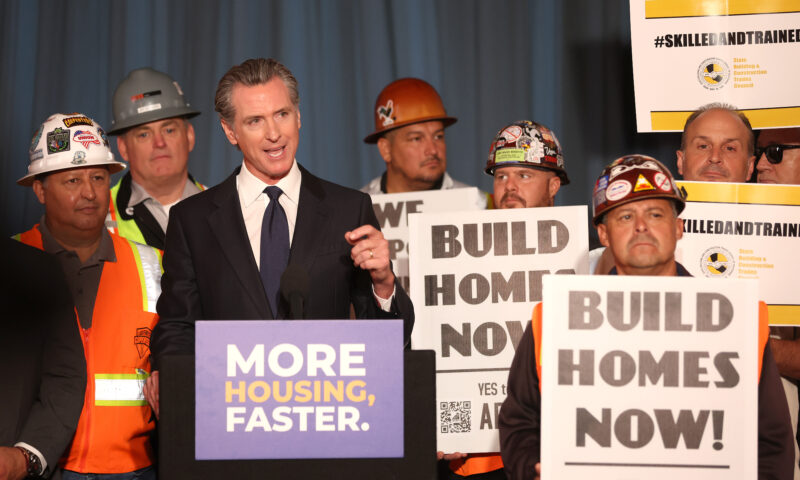

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025Seven Years Into Gov. Newsom’s Tenure, California’s Housing Crisis Remains Unsolved

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025Santa Fe’s Plan for a Real Minimum Wage Offers Lessons for Costly California

-

The SlickNovember 24, 2025

The SlickNovember 24, 2025California Endures Whipsaw Climate Extremes as Federal Support Withers

-

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025Home Care Workers Are Losing Minimum Wage Protections — and Fighting Back

-

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025This L.A. Museum Is Standing Up to Trump’s Whitewashing, Vowing to ‘Scrub Nothing’

-

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025Is the Solution to Hunger All Around Us in Fertile California?

-

The SlickDecember 2, 2025

The SlickDecember 2, 2025Utility Asks New Mexico for ‘Zero Emission’ Status for Gas-Fired Power Plant