For 20 years, husband-wife team Jerry Redfern and Karen Coates reported on environmental and social issues from Southeast Asia. In that time they also taught journalism seminars, particularly in Myanmar in the lead-up to its democratic opening in 2012. Today, Redfern is a reporter with Capital & Main and Coates is fellowship editor at Mongabay. The two recently returned to their past home in Thailand and caught up with old friends now living there.

Journalist Kyaw San Min wasn’t home when the army parked military trucks in front of his family’s shop in Yangon. They had been living in the back of the store for nearly two years when the trucks arrived. When his 12-year-old son ran outside to shut the front gate, soldiers aimed their guns at him and neighbors screamed. The soldiers didn’t fire, but when Kyaw returned home, he knew for certain that his family had to flee Myanmar.

Following Myanmar’s 2021 coup d’etat, he and his family had tried to keep living in the country’s largest city. But the protests grew and then shrank as the military began arresting and then shooting protesters. Kyaw kept working as a freelance reporter as the junta shuttered independent news media. He says that before the coup, friends in neighboring Thailand had been envious of the growing democracy in Myanmar. “But now, the situation is changed,” he says dryly.

When the armed soldiers showed up on their doorstep, he and his wife hoped it wasn’t too late to get out of the country. The family escaped Yangon with speedy paperwork help from a government friend and more luck at the airport, landing in Chiang Mai, Thailand, with no more than what they could carry. Their home and the store that was the family’s savings and retirement plan: lost.

Kyaw now is chief editor of Dawei Watch, a Burmese-language news source that documents the social and physical wreckage wrought by the Myanmar military. The outlet employs a staff of 25, mostly spread across southern Myanmar, working in extreme peril amid a civil war while hunted by a dictatorial government. They send their stories of bombings, arrests and repression to the Dawei Watch office in Chiang Mai — a nondescript, tidy, two-story brick house closely surrounded by trees on a dead-end street in a neighborhood on the far outskirts of this burgeoning, traffic- and tourist-clogged city.

The house/office is mostly empty — reporters and editors tend to work from home. Sometimes, visiting staff sleep in a guest bedroom. When they are there to work, editors sit barefoot (the local custom) gazing at laptops, checking and polishing stories, then pushing them out to the Burmese-speaking world through social media.

“We cannot do very much,” he says. “But we can do something. We can cover the people a little more.”

Those people are the people of Myanmar, who talk with his reporters even though both the government and rebel groups try to silence them. “This shows the media is very important,” Kyaw says.

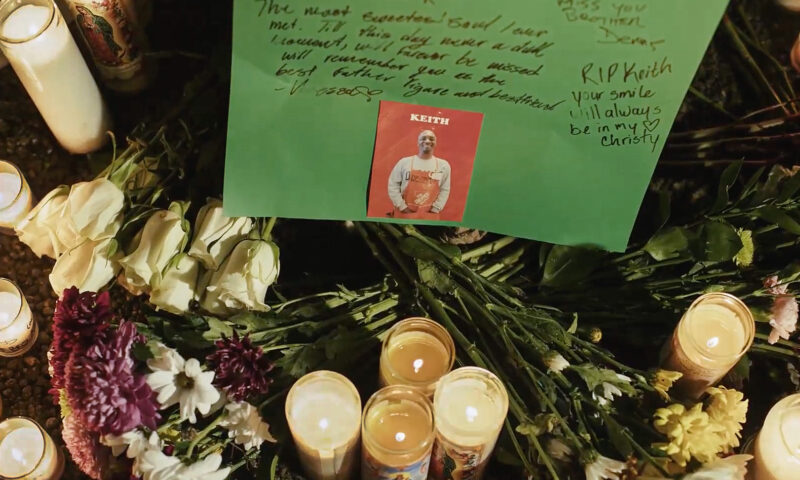

Journalist Kyaw San Min. Photo: Jerry Redfern.

More than 800,000 follow Dawei Watch on Facebook and their YouTube videos garnered nearly 600,000 views in the first 18 days of November. Kyaw says many viewers are in Myanmar, but most are among the 1 million Burmese he estimates now live in northern Thailand. And most of those, he says, arrived following the 2021 coup that toppled the democratically elected government and plunged the country further into civil war.

Many of the topics covered by Dawei Watch are eerily familiar to any American not in a coma: a growing police state, state-sponsored kidnappings and deportations, and the demonization of journalists. Many Burmese we talked to Thanksgiving week were surprised by the return of President Donald Trump to a country they had looked to for lessons on democracy, a country that had long been a safe haven for the most persecuted among them.

Kyaw recounted how he and his colleagues learned journalism ethics through courses once offered by the American Center at the U.S. Embassy in Yangon — where we had taught, many years ago. Today, Kyaw says, those ethics still guide his newsroom: a commitment to fairness, fact-checking and getting the story right.

The two countries crossed paths again Thanksgiving week with the announcement that Trump had canceled Temporary Protected Status for Myanmar citizens living in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said, “It is safe for Burmese citizens to return home,” a comment derided by human rights groups.

Then on Thanksgiving Day, Myanmar’s military government announced it would release thousands of political prisoners sentenced under the country’s notorious “505” law, which, in its broad language, essentially made free speech a crime. The junta also welcomed expatriate citizens in the U.S. back to Myanmar.

Kyaw explained that the facts were not so rosy: Most of the thousands released were people who had been caught at anti-government protests following the 2021 coup — not opposition leaders, not journalists. In addition, people are now being charged instead under the country’s draconian anti-terrorism law. So rather than facing the three-year maximum prison sentence under 505, people face up to life in prison if convicted of terrorism.

Kyaw says he feared the American government would forcibly repatriate people to Myanmar, where they would be prosecuted as terrorists. At the very least, they’d be returning to a country wracked by civil war.

This comes in the wake of another casualty of American foreign policy: journalism. Earlier this year, the U.S. State Department cut critical funding for publications like Dawei Watch and other Burmese-language publications based in Thailand. The U.S. wasn’t the only source of financing, but it had been among the biggest. The money was cut as the Trump administration defunded public broadcasting and demonized journalists at home.

As with many American news outlets, Kyaw isn’t sure how Dawei Watch will cover the funding gap. Some outlets have chosen a predictable path, though. He cites three types of Burmese-language media these days: local, national and “clickbait media.” Before the coup, it was clear which was which. “But after the coup, it is a little changed,” he says. “After the coup, they have no journalism rules.” Kyaw says he has no intention of going that route.

But clickbait is on the rise, because it brings eyeballs, and eyeballs bring money for outlets that rely on Facebook, YouTube and the like. The cut in American funding has increased the importance of those sources for the Burmese-language outlets in Thailand. The civil war feeds that push: People hate the government and want to see stories of its failures. There are publications that want to support the opposition, “So they write the story the people want,” Kyaw says.

In Myanmar, as in the U.S., strife breeds weak reporting and popular disinformation. But Kyaw says he’s sticking to the protocols he learned years ago through the American Center, checking the facts and printing the truth.

* * *

It’s Thanksgiving Day and we are telling Kyaw about the American holiday as we drive across Chiang Mai. He knows quite a bit about the United States already. In 2011, he joined a group of eight journalists from Myanmar who journeyed to Missoula, Montana, to learn about journalism and democracy as his country opened to the outside world following five decades under a military dictatorship. With the help of a State Department grant and friends at the University of Montana School of Journalism — our alma mater — we brought them to western Montana to learn about reporting and democracy.

They watched city council meetings, shadowed journalists from the local paper, toured the state Capitol, met the lieutenant governor and a U.S. senator, went to Glacier National Park (where they saw snow for the first time) and attended a Blackfeet powwow.

In three weeks of surprising encounters and learning, nothing surprised them more than riding along with local cops on patrol. That could never happen in Myanmar, where journalists only ride with police on the way to jail.

The cultural exchange continues years later in northern Thailand — in the city where we used to live, and Kyaw now does. In honor of the famous American holiday, in a place where none of us are really at home, Kyaw gives us a quick, topical Burmese language lesson.

“Kyet sin — chicken elephant!” he says, and we all laugh at the perfect absurdity of the Burmese word for turkey. It’s one of many laughs on a day of grim news, in a time of grim news — the Burmese people have a spectacular way of finding humor in the grimmest circumstances.

When we lived in Chiang Mai in the Aughts, the city had a tiny handful of Burmese restaurants and most of the Burmese in the region worked on farms and construction sites. Now, there are multiple restaurants, Burmese is spoken in the markets and on the streets, and there is a journalism collective as well as several publications, mostly online, that cater to both this diaspora and people inside Myanmar. Kyaw, his wife and two kids are part of an immigrant tide that has changed the flavor of Chiang Mai.

Kyaw drives us all the way across town to the offices of People’s Spring, another Burmese-language online news site. It, too, is in a nondescript middle-class house surrounded by other nondescript middle-class houses, but the neighborhood is gated with a guard who checks Kyaw’s ID and calls ahead to the office.

People’s Spring, an exile media outlet founded shortly after the coup, has a half-million YouTube viewers and 2 million Facebook followers. It publishes 40-50 short news pieces every day, including videos, across all platforms.

Inside the house we meet two top editors: Mr. White and Mr. Black (whom we already know). Karen is also very good friends with Mr. Black’s wife.

The living room is like hundreds we’ve sat in across the region: cool tile floors, dark shades drawn to keep out the midday sun, overhead fluorescent light and a pair of couches where we sit, facing each other, talking. At the far end of the room, a man sits at a computer at a small desk, preparing stories to be published — the nexus of this publishing constellation.

The People’s Spring newsroom in Chiang Mai. Photo: Jerry Redfern.

People’s Spring publishes more stories and has more readers than Dawei Watch, and that brings complications.

“This is the most difficult time for Myanmar media,” Mr. Black says. The two ask that we not publish their photos, take photos of the outside of the house or use their names (Black and White are aliases). No one wants to accidentally incriminate a reporter by using — or even knowing — real names, so all Burmese reporters and editors have two phones: one for family and friends; one tied to a pseudonym used only for work. It’s a protocol meant to protect reporters working in Myanmar.

The consequences of getting caught by the regime are dire. Two Dawei Watch reporters were arrested by the government in December 2023, and tried under the country’s terrorism law. Aung San Oo and Myo Myint Oo were sentenced to 20 years and life imprisonment, respectively, for their work. No one wants that to happen again.

We have already heard, and Mr. Black and Mr. White repeat, that the Myanmar military has spies in Chiang Mai, identifying and keeping tabs on members of the diaspora and threatening their families back home. The huge audience of People’s Spring makes them targets.

Then there are the neighbors, who are all Thai. “We are loud,” Mr. Black says of the usually boisterous Myanmar people, “But Thai people are not.” So they need to be quiet as reporters and editors and video hosts cycle in and out of the house throughout the day.

They give us a tour of the Lilliputian newsroom that pumps out dozens of stories daily to millions: 800 square feet, give or take, including the living room, editing corner, a kitchen and dining area where more people tap at laptops and a windowless room off the kitchen that has been turned into a micro-sized video studio: lights, green screen, a teleprompter. The door to the room is open, and the view out the open back door looks on to the next yard where neighbors walk by. Mr. Black and Mr. White worry that the neighbors think they’re running an online scam shop.

As with journalists everywhere, talk turns to money: how to make it, who is offering it, who is taking it away, what it costs to do business. The first expense for all of them is the cost of a Thai visa. The Thai government doesn’t offer them journalist visas, which are usually issued to journalists working for publications and audiences outside the country. So the most common workaround is a student visa to study the Thai language. It’s not cheap, at about $2,300 a year, and it’s not really why they are in the country, yet the Thai government has allowed it. But rumor has it the Thai government will cancel those visas this year. “Honestly, we don’t know what to do next,” Mr. Black says.

But they all know what they are doing now, and what they will continue to do for as long as they can. It’s what they say American journalists need to learn to do in the face of an increasingly hostile government.

“Every day, telling the truth is more important,” Mr. White says.

“Do your job,” he says.

Copyright 2026 Capital & Main

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026