Labor & Economy

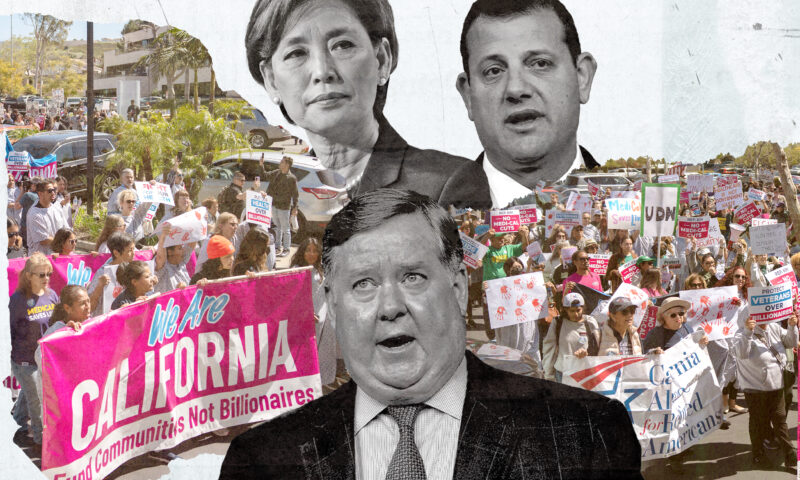

Can California’s Most Vulnerable Survive Obamacare’s Replacement?

Under the American Health Care Act passed by the U.S. House of Representatives last week, California’s half million in-home care recipients, who include the elderly, the blind and the disabled, could be facing big cuts in services.

When Bonnie Kerlew retired from her job as a nurse at the U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in 2005, she wanted to continue helping others. She eventually became guardian to a boy with cerebral palsy, whose family she had been helping, and today she cares for him by herself eight hours a day, plus weekends, in Oceanside.

“After I got to be his guardian, his case worker came to me and asked why I wasn’t on IHSS,” Kerlew recalls.

Also Read — The American Health Care Act: A Nationwide Diagnosis

In-Home Supportive Services is a state program, administered by California’s 58 counties, that pays family members or professionals to care for the blind, disabled or elderly in their homes. For some recipients, the program makes their lives easier; they may need help with basic everyday needs such as administering medication, grocery shopping, cooking and laundry. Many recipients are severely disabled and without IHSS would need to be placed in an institution. Bonnie’s son, Jaime, needs round-the-clock care: feeding, dressing, bathing, personal care and more.

“He has tube feeding every four hours, he’s incontinent, he doesn’t walk,” Kerlew, now 74, says of Jaime. With him being nonverbal, she says, “you have to think for him. But if you look at his facial expressions you know what’s going on.”

Today, as an IHSS care-provider, Kerlew receives $10.50 per hour to care for Jaime, who is 12, every day from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. (Another nurse comes to the home to cover the daytime shift.) IHSS is paid through Medi-Cal, the Medicaid program for low-income Californians, enabling recipients to be with their families, to attend school, and to retain ties to their communities.

But under the American Health Care Act passed by the U.S. House of Representatives last week, Kerlew and Jaime–and the state’s other approximately 500,000 IHSS recipients — could be facing big changes.

The AHCA would change Medicaid from its current financing structure to what’s called a “per capita cap.” Republicans have been seeking to remake the federal health insurance program for the poor since 1981, when Ronald Reagan first proposed a similar change, making Medicaid a “block grant” for the states. Congress passed a bill in 1995 intended to link the amount of the grant to each state’s need, while capping the total amount of federal Medicaid spending, but President Bill Clinton vetoed it. President George W. Bush floated the idea in 2003, but the task force of governors he delegated to figure out the specifics couldn’t come to agreement on a proposal.

Currently, the federal government reimburses states for a share of their Medicaid costs–the average is 57 percent. States must provide a particular set of benefits to defined populations and may add services and eligible beneficiaries. If states’ costs go up, the amount Washington pays rises in tandem.

Under a per capita cap, by contrast, states would get a fixed amount for each person on Medicaid in the state. The amount varies according to the subgroups Medicaid recipients belong to: Caps for children would be set at a particular level; for the disabled, at a presumably higher level to reflect their greater needs, and so on. The cap would rise and fall according to population, but not through other factors, such as an epidemic or natural disaster, which would raise costs, or a medical breakthrough, which would lower them. States would only get paid back for the amount they spend on care up to the cap. If the services cost more than the cap, states would either have to make up the difference out of their own budgets, or cut services.

In-Home Supportive Services is particularly vulnerable to such cuts. It’s regularly on the chopping block in Sacramento whenever the state faces budget difficulties, as in the most recent recession, and because IHSS allows recipients to choose their providers, many are, like Kerlew, family members of those for whom they provide care. So cuts in benefits can hit a family twice.

“AHCA could further constrain the amount of money coming from the federal government to the state, with dire consequences for recipients of [IHSS],” said Kathryn Kietzman of the University of California, Los Angeles’ Center for Health Policy Research. She has published extensively on long-term care of the needy. “That wage is providing not only for the hours of personal care, but is a contribution to put food on the table,” Kietzman said. “More and more family members are going to assume unpaid care if AHCA passes in current form.”

In-Home Supportive Services is growing at about five percent per year, Kietzman said, chiefly due to an aging population (a demographic trend not unique to California). “More demand and less money–I’m not an economist, but if you put those two together that spells trouble for [IHSS] consumers and providers, who are themselves low-income.”

Reduced payments will also have a multiplier effect: If IHSS providers aren’t getting paid, they aren’t spending that money on local businesses, which will reduce their owners’ ability to make payrolls, potentially leading to layoffs–and more people on Medi-Cal or who also need to purchase their own health insurance.

Many IHSS providers get their health insurance through the program and must maintain a certain number of hours to qualify for benefits, often patching together work assignments for several recipients to qualify. If the program is forced to cut recipients from the rolls to save money, providers are likely to lose their health insurance as well as some of their salary–which would make purchasing health insurance on their own more difficult yet. Lower payments to providers would require some to seek work elsewhere; those that are family members would then be left to search for someone from outside the home to provide the care, which in rural areas can be tough to find, according to Kietzman.

The health insurance benefit covers gaps in Kerlew’s coverage under Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly. “I have health insurance and dental through them, and my salary,” she says. “If this deal goes through, I’m going to lose a lot, and Jaime’s going to lose a lot and his quality of care is going to change.”

Changes to Medicaid aren’t the only way AHCA will affect people who provide or receive IHSS. The Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) provided a six percent enhancement for the services; by repealing the ACA, that extra funding will be eliminated. Jennifer Kent, director of California’s Department of Health Care Services, estimated that to make up the shortfall would cost the state $400 million a year beginning in 2020–an amount that would grow annually.

Fiscal hawks often cite the growth in Medicaid spending as a reason to move to a block-grant system. But health economists who have studied the question say that the way to lower a society’s health-care expenses is to make its population healthier. It’s hard to see how reducing the amount of health care people receive achieves that. Cuts to preventive care that Medicaid pays for are likely to result in more serious, more costly health-care needs in the future. If a child is identified early as having a developmental delay–something Medicaid pays for now–she can receive therapy that quickly catches her up with her peers. If states are forced to cut such a benefit because they have to shoulder a greater portion of their Medicaid costs than they do today, that child’s delay will be more costly to address once it is identified; she will be less likely to catch up; and if she doesn’t catch up, she’ll be less productive, earning less over her lifetime and therefore contributing less in taxes to federal coffers–leaving less money to pay for higher health costs.

At the same time, there are other ways to save money on health care. Accountable-care organizations, which coordinate among doctors, hospitals and other providers to give the right care at the right time, have been shown to reduce costs by reducing errors and limiting duplicative care and unnecessary testing and procedures. A trend among HMOs is “shifting from volume to value,” paying doctors and hospitals for the results they achieve rather than the services they provide. That provides an incentive to focus on health, not on costly procedures, and to stay abreast of what the literature says is working and what isn’t.

The irony of the proposed change to Medicaid’s funding structure, which is likely to overburden states, is that the alternative to in-home care–institutionalization–is both much more expensive than caring for the disabled in their homes, and it is a mandated benefit under Medicaid, meaning states would need to make cuts elsewhere to make up the difference. “Even five to 10 hours of help a week can make a world of a difference,” Kietzman said. “It’s a very distinct possibility that recipients will be institutionalized.”

-

Striking BackApril 10, 2025

Striking BackApril 10, 2025USC Follows Amazon and Musk’s SpaceX in Calling Labor Board Unconstitutional

-

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025Democratic and Republican Lawmakers Work to Undermine Voter-Backed Wage and Sick Leave Laws

-

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025A Majority of Californians Support Affordable Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants, Polls Show

-

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025California Showdown Over Medicaid as GOP Approves Massive Cuts

-

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025How Did Farmers Respond When the Trump Administration Suddenly Stopped Paying Them to Help Feed Needy Californians?

-

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025California State University’s Financial Aid Students Learn Chaos 101

-

The SlickApril 30, 2025

The SlickApril 30, 2025Fracking-Powered Crypto Mine in Pennsylvania Shuts Down Without Word to Regulators

-

The SlickApril 16, 2025

The SlickApril 16, 2025In Colorado, Gas for Cars Could Soon Come With a Warning Label