Latest News

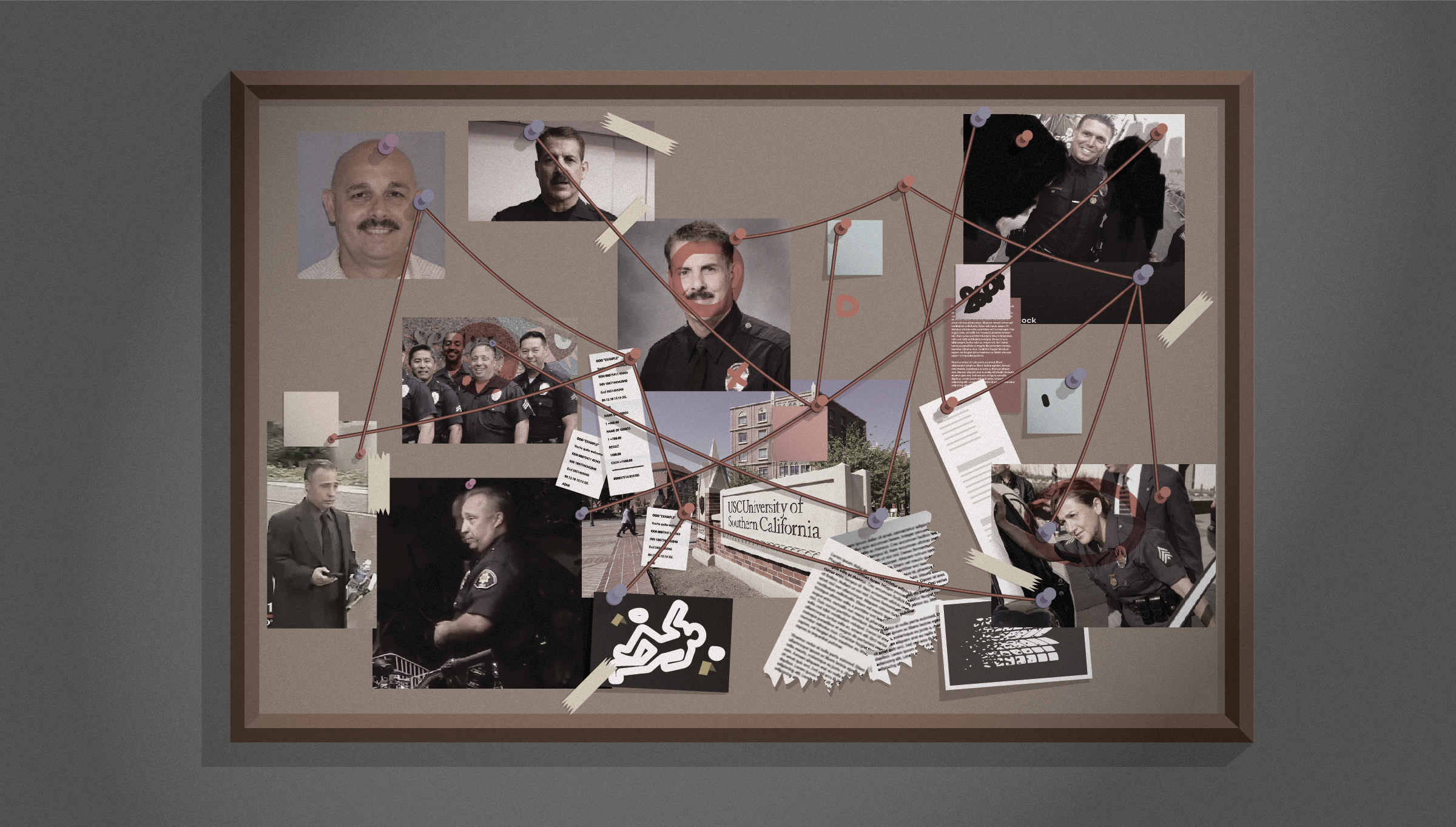

Why Does USC Hire People Fired by the LAPD?

Since 2002, USC has spent more than $550 million on its police force. Community critics say armed officers feel more like an occupying force than a security necessity.

Disgraced LAPD Sgt. Peter Foster cost Los Angeles $1.2 million. Then USC hired him.

In 2011, Black officer Earl Wright of the Los Angeles Police Department sued the city over Foster, his supervisor. When Wright asked to leave work early one day, Foster allegedly asked if he was going to “pick watermelons.” On a separate occasion celebrating Wright’s 20th year with the LAPD, according to the lawsuit, Foster presented him with a cake topped with watermelon and fried chicken. Wright won a seven figure settlement and Pete Foster was fired.

Co-published by Newsweek

Foster would find reprieve from unemployment at the University of Southern California, where he still serves as a lieutenant in the Department of Public Safety. Pointing to controversial hires like Foster, and alleged racial profiling incidents with students and locals, the Service Employees International Union is now organizing to replace USC’s campus police with an unarmed security force.

“These buildings appeared and then, boom — we get campus police everywhere.”

— A community activist

The effort is part of a six-year SEIU campaign to organize faculty, graduate students and workers at USC, the largest private employer in Los Angeles. “This really was an ask from our community partners, something they’ve been pushing for a while,” says Mike Long, a spokesperson for SEIU Local 721, which is headquartered near MacArthur Park. “Brown and Black folks are disproportionately impacted by the overpolicing. That was one of the first things that came up.” (Disclosure: SEIU’s state organization, SEIU California, is a financial supporter of this website.)

Since 2002, USC has spent more than $550 million on its Department of Public Safety, which employs 306 full-time personnel, 114 of whom were armed officers as of 2016. In the 2018-2019 school year the DPS enjoyed a $48 million operating budget, its highest ever. And as the school expands, its police force grows with it, says one community activist who, after this story’s original publication, requested the removal of her name for fear of police retaliation.

This activist grew up in the Ramona Gardens public housing project in Boyle Heights, where USC has dramatically expanded its Health Sciences Campus, recently opening a luxurious 178-unit student apartment complex—“You’ve never lived like this,” its website says, over an image of a swimming pool—and a Hyatt hotel. Rooms at the hotel book for $159 per night.

At USC, already no stranger to scandal, the Dept. of Public Safety has been another consistent, and unwanted, source of controversy.

“These buildings appeared and then, boom — we get campus police everywhere,” she says. “We’re scared to even go outside now with everything going on. They’re not really securing [the street]. It’s more like they’re trying to control it.”

Officers now occupy nearly every corner of the neighborhood, she says, and they regularly stop locals they deem “suspicious” or “out of place,” even kids on their way to nearby Hazard Park.

Another Ramona Gardens native, Michelle Benavides, is a youth organizer with Eastside LEADS, one of the groups partnering with Local 721 to disarm the DPS. She says she saw a police shooting as a child outside her house. The recent sight of armed cops takes her right back. “We don’t need more policing in our community,” she says. “We need resources, we need family therapy.”

* * *

Beyond Lt. Foster, the USC Department of Public Safety employs four other officers with controversial histories who occupy leadership positions: Sergeants Steven Alegre, Rodney Peacock and Frank Trevino, and DPS Assistant Chief Alma Andrade-Burke.

USC Sergeant Steven Alegre participated in three officer-involved shootings, he told an LAPD newsletter called The Rotator in 2013. Alegre was also the subject of an excessive force lawsuit as an officer with the Santa Ana Police Department. In 1984, Alegre and his partner chased a 25-year-old narcotics suspect, Ezequiel Flores Larios, from his car, then struck him on the head with night sticks when he resisted arrest, they said. But two witnesses said the officers struck Larios before and after he was handcuffed, even as Larios pleaded with them to stop.

When asked about replacing the DPS with an unarmed security force, a university spokesperson said two-thirds of campus officers are already unarmed.

Larios died in jail from head injuries. An autopsy confirmed one of the blows to Larios’ head was the cause of death.

A misconduct incident involving current USC Sgt. Rodney Peacock was never shared with criminal defense attorneys, the Los Angeles Times wrote in October 2000, part of a broader pattern investigated by the district attorney’s office after the Rampart corruption scandal. Interrogating a suspect, Peacock dropped a pebble in the man’s pocket and then threatened to arrest him for crack cocaine possession if he didn’t cooperate, according to the district attorney’s office.

On December 2, 2004, the LAPD charged Frank Trevino with five counts of misconduct, all for resisting an internal investigation after a suspect accused Trevino of taking $100 from him. Trevino was then fired.

Lastly, in 2003, DPS Assistant Chief Alma Andrade-Burke, then LAPD Officer Andrade, shot and killed Yousuf Mollah, a Bangladeshi native accused of exposing himself to children. Andrade and her partner said Mollah lunged at them with a knife when they entered his apartment.

Then in 2014, the LAPD assigned Detective Andrade-Burke to investigate the controversial killing of Ezell Ford by officers Sharlton Wampler and Antonio Villegas. Basing its findings in large part on Andrade-Burke’s investigation, the district attorney’s office concluded the officers acted lawfully in self-defense, but the Los Angeles Police Commission disagreed, rejecting the findings and ruling that Wampler and Villegas improperly used lethal force.

Some students say DPS officers scrutinize and harass people of color on campus — both students and neighborhood residents.

When reached for comment, a USC spokesperson said the Department of Public Safety conducts extensive background checks when hiring armed officers. The spokesperson also pointed to the department’s diversity: nearly 49% of officers are Latino, 30% are Black, and only 13% are white.

But at USC, already no stranger to scandal, the Department of Public Safety has been another consistent, and unwanted, source of controversy.

Some students say DPS officers scrutinize and harass people of color on campus, whether they are students or residents of the neighborhoods around the school’s South and East L.A. campuses.

“It’s funny how USC claims the village is supposed to be shared with the South Central L.A. community, yet DPS always escorts local Black people out of the village for ‘looking threatening/suspicious,’” an unidentified member of the class of 2023 wrote to the Black at USC Instagram.

The Village, a “groundbreaking retail-and-residential development” with a Target and a Trader Joe’s, opened in 2017 adjacent to USC’s main campus. Another student, an unidentified member of the class of 2017, wrote of being harassed by campus cops even while being asked by USC to sit on diversity panels: “I wish I could have shared the racist experiences I encountered on campus but instead I had to smile and wave for diversity quotas because I didn’t want to lose financial aid,” the student wrote.

In 2013, more than 70 Public Safety and LAPD officers—some in riot gear—shut down a party at a Black fraternity, arresting six students who would later receive a $450,000 settlement approved by the L.A. City Council. Then in 2015, DPS Officer Miguel Guerra crashed into and killed a graduate student in his car.

According to the wrongful death lawsuit filed by the student’s parents against the officer and USC, Guerra had worked back to back graveyard shifts and was driving 69 miles per hour without his siren or lights on. A court convicted Guerra of manslaughter, but he still works for USC as a campus police officer.

When asked about replacing the DPS with an unarmed security force, a university spokesperson said the majority of criminal incidents at USC don’t require armed officers to respond. And two-thirds of DPS officers are already unarmed.

“However, like other university departments across the country, it is important for DPS to have officers trained and equipped to respond to serious events,” the spokesperson added.

In Ramona Gardens, however, says Michelle Benavides, armed officers feel more like an occupying force than a security necessity. In the summer of 2017, DPS officers pulled over her and her friends in a parking lot within the Keck Hospital complex in Boyle Heights.

“My homies look like homies, they don’t look like USC students,” she says. “Would they have stopped a doctor?”

And ever since USC began expanding near Ramona Gardens, when her friends’ brothers make trips out of the house, they’re sure to take their sisters with them, she says. Just in case something happens.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.