Coronavirus

Why California’s Undocumented Immigrants Remain Vaccine-Resistant

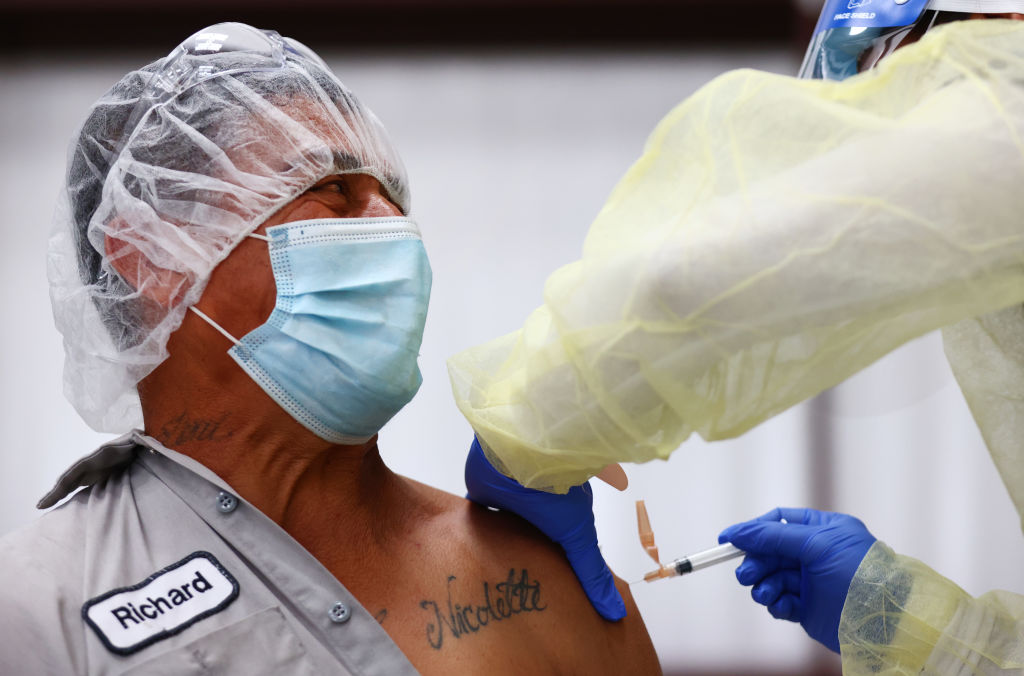

Some workers fear revealing their undocumented status at vaccination sites. It takes the spread of only a few stories to stoke those fears.

As it became apparent over the past weeks that the supply of COVID-19 vaccine wouldn’t be a significant issue in California much longer, the challenge to the state’s vast network of rural and community clinics seemed clear. Job one for health workers was to allay concern about the safety of the vaccine itself, especially among immigrant populations that might be wary of receiving a shot.

That remains a challenge. “It is slow going and a lot of work,” Dr. Melissa Marshall, CEO of five CommuniCare clinics in Yolo County, told Capital & Main on Friday. “Many are hesitant due to fears of vaccine side effects.”

Like almost everything associated with California’s vaccine rollout, a don’t-ask-don’t-tell directive’s execution has been spotty, resulting in some people being turned away for vaccination.

Relieving those worries is a large ask. But there’s a second complication that has put this outreach effort into a more perilous state: Some workers fear having their undocumented status exposed if they show up for a vaccine. And it takes the circulation of only a few stories to stoke those fears.

In Southern California last month, the retail behemoth Rite Aid apologized to undocumented immigrants who were denied COVID vaccinations in separate incidents at two pharmacies, saying the women were mistakenly turned away by employees who either didn’t know or didn’t follow established protocols for eligibility. In Florida, meanwhile, intentionally strict ID requirements have put nearly a million undocumented immigrants and seasonal workers at risk of not receiving vaccines, and in other states, patients have been asked to pay for their shots, when in fact they are never to be charged, per the CARES Act.

“It’s slowing down our path to recovery,” Marielena Hincapie, executive director of the National Immigrant Law Center, told the Miami Herald. “President Biden has been clear that anyone, regardless of their immigration status, is eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine, and yet we’re seeing people get turned away in some places as states and localities have adopted their own burdensome requirements for verifying eligibility.”

In fact, states and communities are largely free to set their own rules as to who can or cannot receive a vaccine. There is no federal law in this regard, although Biden’s administration has made its position clear. On Feb. 1, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) called vaccinating every U.S. resident, regardless of immigration status, “a moral and public health imperative.” It added that the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency would not carry out enforcement procedures at or near health care facilities.

* * *

California’s state guidelines are straightforward. “You can get the vaccine for free no matter what your immigration or citizenship status is,” the state’s COVID-19 guide states. “You should not be asked ”about such status when receiving a vaccine, it adds.

Like almost everything else associated with California’s vaccine rollout, though, the directive’s execution has been spotty, and in some cases it has resulted in people being turned away for vaccines. In part, that’s because of the state’s midstream shift to the MyTurn web portal and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s awarding of the vaccine distribution contract to Blue Shield, a longtime political contributor.

For those who access the MyTurn portal, a series of personal questions can be daunting – and they might lead some undocumented immigrants to avoid the process altogether.

Those decisions functionally removed community and rural clinics, and their institutional knowledge of their patients’ needs, from the state’s officially designated vaccination campaign. In so doing, they took the process largely out of human hands and into a realm dictated by connectivity.

“That’s why we’ve been so intense about avoiding the MyTurn system,” Andie Martinez Patterson, a senior vice president with the California Primary Care Association (CPCA), said in an interview. “Not because it wasn’t designed to do good things, but because it was built for populations that are not the hardest to reach. If you’ve got great connectivity and access to computers and laptops, that system can work for you. That’s not who we reach.”

The CPCA represents nearly 1,400 not-for-profit community health centers and regional clinics up and down the state, often working with immigrant patients who have no insurance and little ability to pay. “We know our communities. We know what questions to ask,” Martinez Patterson said. “We don’t need your [MyTurn] system.”

Instead, clinics have continued working directly with their patients – with the state’s blessing. That has become common; appointments booked through MyTurn account for only 27% of the total vaccinations administered daily in California, according to data compiled by CalMatters, as local and county authorities bypass the state system and continue distributing their own allotments of doses. For those who do access the MyTurn portal, a series of personal questions can be daunting – and they might lead some undocumented immigrants to avoid the process altogether.

“That’s exactly what we don’t want,” Martinez Patterson said. “The truth is, we don’t need to know almost anything other than whether you’re old enough to receive the vaccine, have a health issue or recently had COVID. It’s a minimal amount of information. Going through the MyTurn survey can scare people off.”

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, about 2.3 million of the state’s immigrant population is undocumented. Vaccinating the age 16-plus contingent of that total would certainly meet the DHS description of a public health imperative, and the community and rural health system is the most effective way to do that.

It also may represent the best hope for California to avoid the kind of situation brewing in Florida, where Democratic leaders are pleading with the state’s conservative governor, Ron DeSantis, to relax some of the strictures that are preventing undocumented workers from being vaccinated and intimidating others into not even trying.

In Yolo County, where immigrants are heavily employed in farm labor, Dr. Marshall’s health workers often know their patients by name and are familiar with family histories. That kind of intimacy may allow them to reassure undocumented workers that they can both safely receive the vaccine and do so without any threat to their futures.

“I tell them any form of ID can be brought in, even if it’s their Mexico ID,” said a CommuniCare employee, who answers patients’ questions in Spanish and is part of an aggressive outreach program. “Many of them already know they can receive the vaccine – it’s been only two or three [callers] that have been worried about what form of ID to bring.”

That is the absolute value of community and rural health practice – and it could be the way through this latest challenge.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care