Labor & Economy

Barron of Frogtown: Watching L.A. change with “the Willy Wonka of rusted metal”

Frogtown, also known as Elysian Valley, is yet another Los Angeles neighborhood being transformed by gentrification.

Barron Gunter and his girlfriend Michele Jafe sit on metal stairs that Barron welded in front of their raised airstream trailer which serves as their bedroom.

FROGTOWN REGULARLY SEES ITS SHARE OF GARAGE SALE TREASURES, but a Vietnam-era minesweeper out of the original box with khaki wearable harness is probably not everybody’s must-have. Browsers milling about the Denby Street lot on a slow summer Sunday, a block from the Los Angeles River, picked over other curious items: tube-powered stereo components, two 35mm film carriers, a rack of used jeans, a polo mallet, a propeller from the aviation maintenance plant that used to be across the street, where condos are going up now.

A young couple deliberates over a mid-century Danish Modern record console.

“Make me an offer,” says Barron Gunter.

After nearly a decade in the obscurely located neighborhood in LA’s 13th City Council District of nearly 8,000 inhabitants politely known as Elysian Valley, Illuminati Motorcycles received a 60-day notice from the landlord in June, and now everything in Gunter’s shop has to go. We’re talking more than 40 motorcycles in various states of repair; motorcycle parts in buckets, stacked on shelves, dangling from the rafters; and a mad antiquarian’s collection of things entirely unrelated to motorcycles, all arranged as if by “the Willy Wonka of rusted metal,” according to one Yelp review.

Barron Gunter prepares for a garage sale at the space next to his shop. He hopes to sell several of his belongings before his move date.

Barron Gunter “gives the kids in that neighborhood jobs, puts money in their pockets, and they all go to him for help and advice. He’s a cornerstone there.”

The owner putters around the 8,000 square feet of tin-roofed working space almost entirely surrounding a small house dominated by an Airstream, 20 feet up on stilts, that serves as main living quarters for the stocky, 53-year-old Barron, habitually unshaven in jeans and sweat-stained T-shirt, his girlfriend Michele Jaffe by his side in black vinyl pants and red leather stiletto boots. And don’t forget Pookie the dog.

Barron Gunter’s girlfriend Michele Jaffe and their dog Pookie at their home space/vintage motorcycle repair shop.

Barron’s landlord wants to move back into the ever-more-valuable space, and Barron’s ability to afford what a new lease would cost—with his revenues mainly from repairing vintage Japanese bikes of the 1960s and ’70s—is what it is.

You could say Barron’s shop, chosen by LA Weekly in 2011 as “L.A.’s Best Motorcycle Shop,” has fallen victim to gentrification. The $1.4B river revitalization project now underway is helping to boost real estate values, with high-end residential construction rising over the modest bungalows of this historically Latino/Asian community, adjacent auto demolition lots, and small machine shops like Barron’s. Many families landed here after displacement from Chavez Ravine in the 1950s to make room for Dodger Stadium. Today home prices have zoomed from an average of $286,000 in 2010 to $730,000, with average rents rising from $1,800 to $2,800 a month, according to Zillow.

A $1.4B river revitalization project has boosted average home prices from $286,000 to $730,000 in a Latino/Asian neighborhood of modest bungalows.

An expanding beachhead of hipster java joints, eateries like the one selling sandwiches named after NPR hosts, and the Spoke Bicycle Café close by the riverbank bike path, cater to increasing numbers of well-heeled visitors like comedian Patton Oswalt and celebrity neighbors like the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea and Portlandia’s Fred Armisen. That should be good for business, so maybe chalk up some of Illuminati’s difficulties to Gunter’s notoriously casual approach to capitalism. “He’s so not a businessman,” one of the shop’s clients tells me, adding, “He won’t even touch your bike if he doesn’t like you.”

New businesses are opening directly across from modest Frogtown homes. Openings include a new pizza parlor and a vegan bakery.

CALL IT FROGTOWN OR ELYSIAN VALLEY, residents say the inexorable pace of change here is quickening. Years of community meetings and municipal planning and public-policy studies addressing the benefits of real estate market forces versus preservation, building density versus population increases, Floor Area Ratios versus up-zoning versus down-zoning, have all failed to stem what many locals are seeing: the steady loss of intangible assets that cannot be measured in square feet, demographics or dollars.

Hipster java joints, eateries like the one selling sandwiches named after NPR hosts, and the Spoke Bicycle Café cater to increasing numbers of well-heeled visitors.

“He’s buen amigo, a good friend,” says 13-year-old Chuy Morales, leaning against the fence of his house on the next corner up the street from Gunter’s shop. The Sotomayor Learning Academies student says he’s known Barron all his life. “My father helped El Tejano move in 10 years ago,” he says, calling the blue-eyed native Texan by his nickname hereabouts. He mentions that Barron, who has no children of his own, was named padrino (godfather) to one of the local kids in a family church service.

Barron Gunter’s workshop is filled with a variety of tools and machinery.

The shop has nurtured a parade of folks walking in off Frogtown streets and beyond. In return for pushing a broom and sorting out buckets of bolts, they become what Barron calls “my acolytes”—participants young and old in an informal intern program in which they learn something about fixing motorcycles, and something more about critical thinking, character, integrity, fair play, having a certain sense of humor, and the nature of work itself.

“My whole life is going off to the scrapyard,” Barron says, surveying his metal domain.

“‘Fuel or fire,’ he’ll always say when checking for what’s wrong,” says Angela Day. She is repeating one of many “Barron-isms,” reducing a bike’s problems to either its gasoline lines or the electrical system. The 40-year-old Long Beach native and bank analyst brought her 1972 Honda SL Enduro to the shop a few years ago, becoming one of Barron’s acolytes. “He showed me how to do basic maintenance, gave me a skill set, and I just started hanging around,” she says, assisting with oil changes, putting bikes up on the lift (often to the amazement of male customers), while observing Barron’s interactions with Frogtown’s diverse populace. “He gives the kids in that neighborhood jobs, puts money in their pockets, and they all go to him for help and advice. He’s a cornerstone there.”

This vintage Ducati is one of Barron’s most cherished bikes in the shop.

MY OWN KID, in fact, is how I first heard about Barron. After graduating from college, Carlos kicked around a bit, drumming in a band, working in a restaurant, figuring things out. Buying his first motorcycle for cheap transportation, he called Barron for advice. In short order, my college grad was sweeping the shop floor, sorting nuts and bolts and then earning certification in motorcycle repair from a Honda specialist—possibly more practical than his diploma. From cleaning carburetors to learning how to weld, he’s gone on to bigger things, but at the time I was pleased my son had found a mentor in this eccentric character, someone not unlike the rough-edged types I grew up with in a small upstate New York town.

“You can’t just walk into a media company office and offer to sweep the floor,” says Steven Appleton, 17-year Frogtown resident, artist and property owner. He was referring to the kinds of businesses replacing the woodworking, welding, baking and other small manufacturers that used to provide walk-to-work living wages for the community.

This newer restaurant in Frogtown serves sandwiches named after NPR hosts.

Appleton’s out-of-the-box attempt to provide “green” local employment opportunities—LA River Kayak Safari, of which he’s co-founder— is an icon of the area’s revival but has come under criticism for being an agent of gentrification.

Illuminati Motorcycles fits into the neighborhood’s matrix of “makers,” the term used in a 2015 report by non-profit urban design organization LA- Más to bridge the gap between industrial shops like Gunter’s and newer arrivals such as the Coarse Gallery workshop a few doors down towards the river. Trouble is, that gap is measured not just by money but also by the range of characters inhabiting the neighborhood, according to LA-Màs co-executive director Helen Leung, a Frogtown native and daughter of two familiar local characters. “My mother is the lady with the lawn sales, selling a vacuum cleaner for two dollars she found in the trash and fixed up,” says Leung. “My dad is the Chinese recycling guy on the bicycle.”

Leung is also a board member of the Elysian Valley Arts Collective. Her parents still live in the home where she grew up before going east to get degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard in public policy and urban planning. Since interning in Eric Garcetti’s office during his time as city councilman for the 13th District, Leung has seen her deep immersion in the neighborhood’s issues lead more recently to the 10-month project produced by LA- Más titled Futuro de Frogtown, a “co-visioning process to understand what community members—both new and long term—want to see (or not see!) in their neighborhood as it inevitably changes.” Leung admits that the project’s ultimate report does not reach the granular level inhabited by oddball characters like Barron Gunter (and her parents). Their loss unravels, thread by thread, what Futuro de Frogtown calls the neighborhood’s “unique tapestry.”

Meanwhile, under the tin roof, Barron is reticent about himself, deflecting questions about his business with wry jokes.

Barron Gunter at his vintage motorcycle repair shop in Frogtown.

“My whole life is going off to the scrapyard,” he says, surveying his metal domain. But he’ll take you up into the nearby hills above the river and show you places where the hidden history of this part of the city comes alive, pointing out ghost stairways, abandoned train track paths and bare, ruined pylons where a bridge once connected Elysian Valley to the rest of the world before its encirclement and isolation by labyrinthine freeways. “This place used to be…” he says, gesturing off into the hazy distance. Without finishing the sentence, he’s expressing something about Los Angeles, something about all cities, and something about himself.

All images by Joanne Kim

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

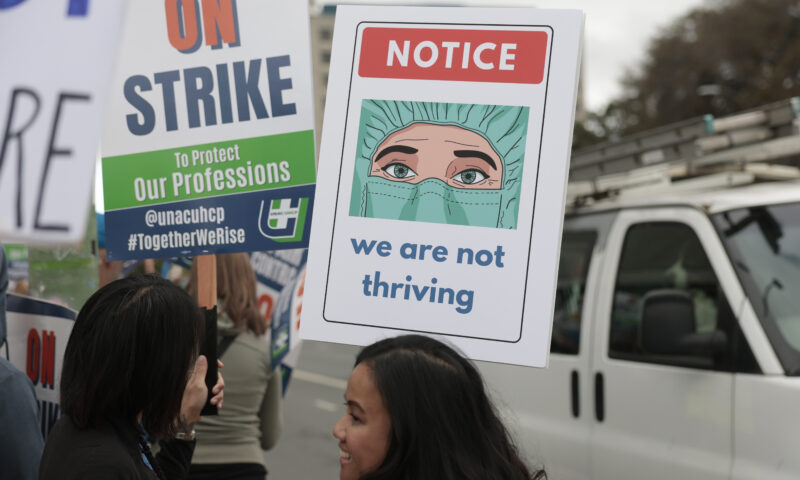

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas