Latest News

Warriors of the Sunrise vs. New York State

In one of the wealthiest areas in the country, the Shinnecock Nation fights to survive as Thanksgiving approaches.

The leaves have mostly fallen in the pitch pine and oak forest that stretches along the Sunrise Highway in Hampton Bays, New York, where four Shinnecock women—Jennifer Cuffee-Wilson, Tela Troge, Margo Thunderbird and Becky Hill-Genia, the Warriors of the Sunrise of the Shinnecock Nation—are taking a stand on the tribe’s aboriginal territory. They are protesting legal maneuverings by state and local governments they say inhibit their economic prospects.

Acorns and twigs crunch underfoot as the near constant whoosh of fast cars is tempered by whistling sparrows, warblers and common yellowthroats.

“Six hundred years ago we’d be over here now anyway,” says Margo Thunderbird, one of the camp’s founders. “We’d be hunting, fishing, drying hides among the trees. We’re right where we’re supposed to be, when we’re supposed to be.”

The Sovereignty Camp, which began occupying the strip along the highway on November 1, has attracted 35 dedicated campers since it issued a call to action October 25.

New York’s attorney general is suing to challenge the tribe’s authority to mount and sell advertising on two roadside monument billboards near the camp.

“Six hundred years ago we’d be over here now anyway,” says Margo Thunderbird. “We’d be hunting, fishing, drying hide among the trees. We’re right where we’re supposed to be, when we’re supposed to be.”

Tela Troge, an attorney who serves as the tribe’s COVID-19 officer, has been actively working on raising awareness. “I don’t take any day for granted,” she says. “I literally wake up every day thinking about how to move us forward a little.” Through direct actions and political education, the warriors aim to alert Long Islanders to what they call economic violence against the region’s First Peoples. Troge feels that if her neighbors really knew how bad it was, they would care.

In one of the richest ZIP codes in the nation, the 600 or so Shinnecock who live on the reservation had a per capita annual income of $8,863, according to the 2000 census. Even if doubled or tripled, in the Hamptons those numbers would still leave the Shinnecock struggling in substandard and overcrowded housing during a pandemic. Hill-Genia’s mother, daughter and grandchildren all live in her small home with her, and Cuffee-Wilson lives in an insulated tent pitched out back.

“Things were bad before COVID, but things are just very, very bad now,” says Troge. “We need that money to feed people, buy our babies formula and diapers and for our elders’ plumbing and heating, and to make sure they don’t have a giant hole in the side of their house as we’re approaching winter. How do you quarantine like that? It’s a desperate alarm that we’re trying to sound.”

Thunderbird, a lifelong activist in the American Indian Movement (AIM), has been working to raise living standards for nearly 50 years. Though she’d rather it wasn’t needed in this instance, the camp is a long-held dream come true. “My grandmother saw the quiet, under-the-table dirty deals selling off our lands and urged me to go to the AIM occupation in Alcatraz when I was only 17. She wanted me to be a fighter for my own people here in the Hamptons. Billionaires are all around us on our stolen land, and we’re poor and hungry and have to talk about what we don’t have?” says Thunderbird. “Enough!”

* * *

In 1936, John Collier, the commissioner of Indian affairs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, denied the Shinnecock status as a federally recognized nation under the Indian Reorganization Act, following a report from an agent who had visited the tribe and referenced the Indians’ skin color and hair texture. (Natives had intermarried with formerly enslaved and free Africans.) Denial meant they didn’t receive federal trust lands, which set them up for exploitation at the state and town levels. After a 32 year court battle, federal status was conferred in 2010, which in theory positions the tribe to pursue gaming. But the monument billboards are the tribe’s best hope for a near term infusion of cash.

They want New York Attorney General Letitia James to drop the lawsuit to stop construction and operation of two electric monument billboards. Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman told the New York Times in May 2019 that the signs were “clearly out of character” with the town’s low-rise, low-key style, and that they “violate the spirit of our local ordinances meant to protect the rural character of the town.” He worried that New Yorkers escaping the city would be met by an “urban element at the gateway to the Hamptons.”

New York’s lawsuit claims the tribe did not pursue proper permitting and has not deferred to state authority over traffic safety. (The attorney general’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Troge sees the lawsuit both as an attack on Shinnecock autonomy and as a possible pressure tactic to get them to cash in and move off their lands.

“They’ve already done that historically, and they definitely have their eye on this land; they’ve valued it out,” she says.

Schneiderman has previously seemed to underscore the claim. In a 2019 documentary film, Conscience Point, he said:

“They’re sitting on one of the most valuable pieces of land in the country and they could generate income from that land; they could all be millionaires, literally. But they can’t seem to get behind any one idea and stick with it for very long. I don’t know what’s the right economic development direction for the Shinnecocks; it’s really up to them, but they have opportunities. The town is not standing in their way.”

“Billionaires are all around us on our stolen land, and we’re poor and hungry and have to talk about what we don’t have?” says Thunderbird. “Enough!”

Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who owns a 22,000-square-foot Georgian mansion on a 35-acre estate in Southampton, has been invited to visit camp. Last February, during his failed run for the presidency, he called the Shinnecock Nation “a disaster,” a comment that still stings, say tribal members. In turn, the Sunrise Warriors have called on Bloomberg to pay his back rent for living on their stolen land.

The women have published demands for redress from specific local, state and federal policies that undermine the tribe’s ability to self-determine. In a Zoom teach-in held on October 30, Hill-Genia gave voice to the ugly truth: “We are silent no more. We have had it up to here and then some. We have been your slaves, Southampton Town, we have been your servants, your prostitutes, your lawn keepers, and we are more than that.”

Zoom meetings, online informational panels and social media outreach have all been employed to engage the wider community. Roger Waters of Pink Floyd visited the camp and committed support. But not all their efforts at outreach have been welcomed warmly. “We went live on Instagram with the New York Communities for Change car caravan to the billionaires’ houses, and all the superwealthy people went on a hiring frenzy for armed security,” Troge says.

* * *

The spiritual center of Sovereignty Camp is the Unity fire, which was lit the night of October 31 and will burn until the close of camp on November 26, Thanksgiving, considered by the warriors to be a national day of mourning. It’s been tended day and night through rainstorms by fire keepers. Coals from the Unity fire are carried to the kitchen fire and then to a fire near the highway in a continuous circle. It’s a big responsibility to keep everyone safe and warm as nighttime temperatures plunge into the low 30s.

“Come to the fire and learn about what you say you’re standing up for,” Thunderbird says to the campers, some of whom are from New York City and have never dug a fire pit. “When we’re all chopping wood and talking, the Warriors of the Sunrise are also gathering our allies.”

Allies include the Long Island Progressive Coalition, The Red Nation, DSA Suffolk and Cooperation Long Island, who have provided tactical assistance including a successful GoFundMe campaign, social media support and the Zoom infrastructure for mass meetings.

Lou Cornum (Diné), chairperson of The Red Nation — East Coast, a Native liberation group, says the gratitude flows both ways.

“It’s my first time on Shinnecock land,” Cornum says. “We’re here not under ideal circumstances, but it feels so nourishing, especially at a time when politics as usual feels so draining. It’s a giant mutual aid project and I’m already preparing my spirit for the melancholy I expect I’ll feel when it ends.”

Thunderbird says a traditional Shinnecock feast held on the third Thursday of November called Nunnowa would be held at Camp Sovereignty this year. It’s a community event and a time to remember the ancestors.

“Our elders, those grandmothers and grandfathers who have passed on, would be very proud to be here,” she says. “I know they are standing with us. Their spirit is here with us at camp, so it’s a very full and beautiful place. We call our ancestors in song with a big drum, and the land is blessed. They know we’re here.”

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

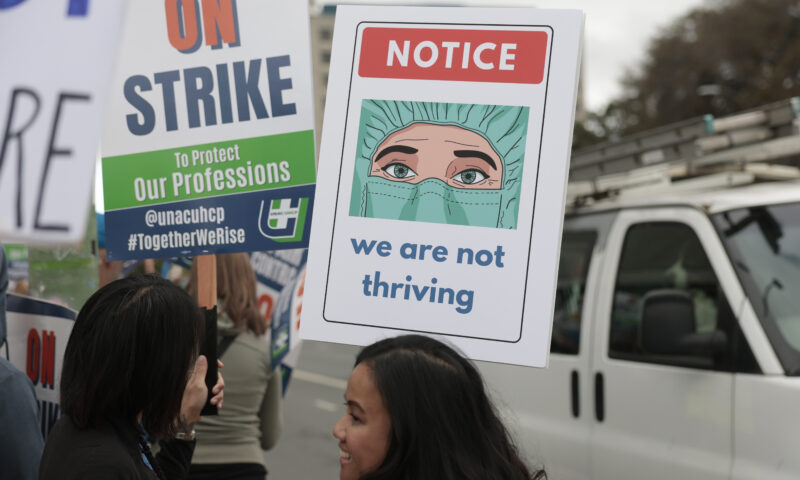

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?