Labor & Economy

Walmart and L.A.’s Post-CRA Landscape

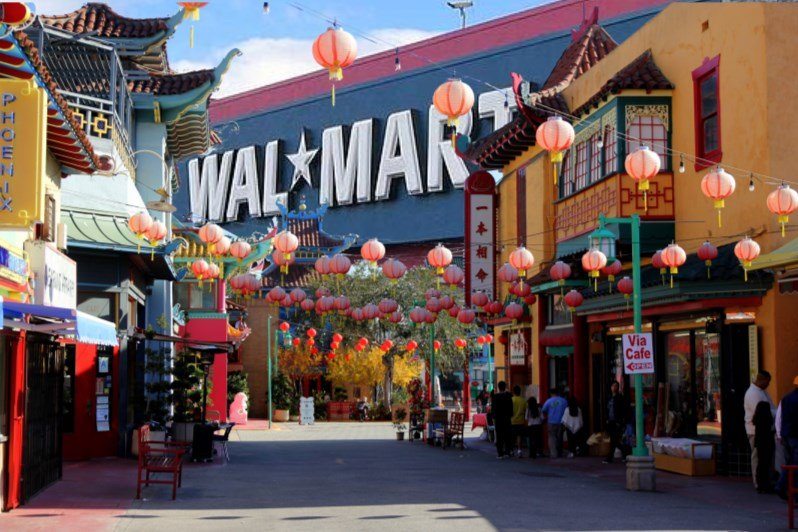

Last week a Superior Court judge dismissed a final attempt by community groups to score a victory against the Walmart grocery market that opened in Chinatown last year. The groups’ complaint against Walmart brings up a number of factors that undermine the validity of the Chinatown store’s permits. These include zoning and redevelopment requirements that have not been met, poor record keeping by the City, the lack of current California Environmental Quality Act information about the neighborhood, and the fact that the permits were issued the day before a City Council hearing that could have halted the project.

Walmart has long occupied center stage in the national debate about income inequality because of its low wage jobs and ruthless ability to undercut small local businesses. How, then, did the retail giant plant a 33,000-square-foot flag in the middle of Los Angeles’ urban core, despite long-established safeguards designed to protect the unique neighborhood character of places like Chinatown?

Veteran planning experts and neighborhood activists point to the dissolution of the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA) as a key factor. When Governor Jerry Brown decided to reallocate funding to other areas in 2012, redevelopment agencies across the state disappeared – and, along with them, the ability of California cities to provide their growth strategies with smart planning.

“The whole idea was that if you’re going to invest in a neighborhood, the benefits should go to that neighborhood,” Donald Spivack, the former Deputy Chief of Operations and Policy at the CRA, tells Capital & Main. The agency’s primary responsibilities involved creating affordable housing, revitalizing physically and economically depressed neighborhoods, and facilitating economic development in underserved areas. The CRA steered development toward neighborhoods in need of economic investment and ensured that new projects provided good jobs and other positive elements.

When the CRA was dissolved during the state budget crisis, it left a legacy of rules governing development – rules that were ignored by the city when it granted Walmart its permits to build out the grocery store location near the corner of Cesar Chavez and Grand avenues.

According to Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE) co-founder and former CRA commissioner Madeline Janis, the CRA created “specific requirements about how to do development” in Chinatown. The CRA was also the “watchdog” in charge of overseeing these policies, and its dissolution left uncertainty about who should enforce the rules.

“Walmart was able to slip through that lack of clarity,” Janis tells Capital & Main.

Gideon Kracov, the attorney representing the community groups challenging Walmart, agrees that the absence of the CRA helped Walmart sidestep Chinatown’s longstanding development policies by creating confusion about the enforcement of CRA regulations. Adding to the uncertainty, City documents from December 2012 indicate that the functions of the CRA were meant to be transferred to the Department of City Planning, but Kracov claims this has yet to actually happen. He says the CRA is still operating with a “skeleton staff” and an outdated website, although it is unclear what duties the gutted agency still has.

While Walmart’s location, which had originally been slated to be a Boys Market, had been plagued by a series of changing developers and remained vacant for years, community groups such as the South East Asian Community Alliance (SEACA) and LAANE believe that having a Walmart in the neighborhood is the wrong kind of development, and that the CRA regulations to prevent this exist for a good reason. Before its dissolution, the CRA might have been able to provide the oversight necessary to ensure a sustainable development in place of the Walmart grocery store. According to the CRA’s “Chinatown Redevelopment Project,” a document that dates back to 1980, any building permits in Chinatown are subject to the CRA’s approval.

The uncertainty that has allowed Walmart to move in comes with a potential cost to the community. Sissy Trinh of SEACA spoke to Capital & Main about Walmart’s likely negative long-term impact on the neighborhood. Trinh cites Chinatown’s large number of “small mom and pop businesses” as the primary reason the community is vulnerable to Walmart’s influence. According to Trinh, 300 of these small businesses are in “direct competition” with the chain retailer. She adds that Walmart’s presence could also “add to blight” if shops in the area have to shut their doors.

While community groups think Walmart’s presence could be damaging to the neighborhood, the CRA issue is not just about big box retailers, and according to Spivack, big box stores can even add to growth under the right conditions. However, without the CRA in place to enforce its own policies for sustainable redevelopment, developers can take advantage of the lack of authority and work around regulations designed to benefit communities. This can mean different things for different neighborhoods, but according to Janis, disadvantaged communities face the most risk without the kind of oversight the CRA once provided.

Chinatown photo: Sgerbic/Wikimedia

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit