Culture & Media

Unjust Desserts: A Review of ‘My Mañana Comes’

It’s often apparent at countless restaurants around the country that the hardest working employees are the bussers, with the “back of the house” providing the foundation for the entire culinary enterprise.

It’s often apparent at countless restaurants around the country that the hardest working employees are the bussers, with the “back of the house” providing the foundation for the entire culinary enterprise. That said, they are also the lowest paid in the service industry’s economic food chain, and the meager wages can make it difficult to forge a life beyond their weekly schedules.

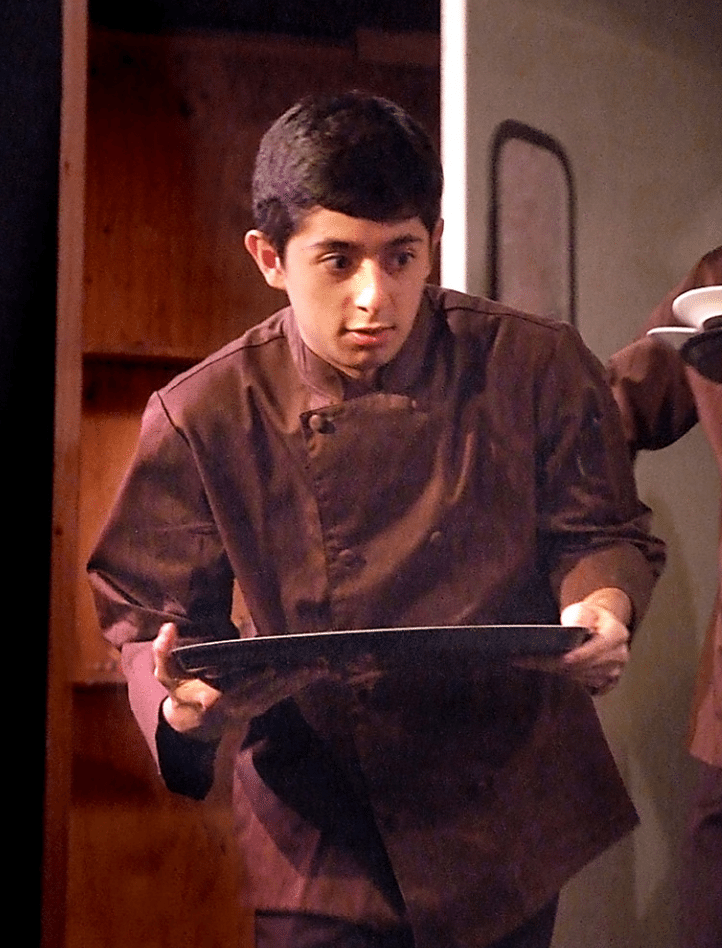

The four busboys in Elizabeth Irwin’s My Mañana Comes, now running at Los Angeles’ Fountain Theatre through June 26, serve as archetypes for those who toil behind the scenes every night in America’s eateries. And for this quartet, the recipe for their future calls for gallons of sweat and a sprinkle of hope, topped off with a dollop of powerlessness.

Mañana ’s workers pour, fold, wash and carry their way through shift after shift in the back kitchen of a posh Upper West Side French restaurant. There is Peter (Lawrence Stallings), a stand-up guy constantly staggered by misfortune, who has his sights set on a managerial job at the chef’s next venture. By his side is the diligent and frugal Jorge (Richard Azurdia), who has spent the last four years cautiously saving money to build a big house for his family back in his home in Pueblo, Mexico. Under his wing is Pepe (Pablo Castelblanco), a wide-eyed immigrant who is struggling to learn at once the ways inside and outside the kitchen, and who also awaits the arrival of his brother to join him in pursuing the American Dream. Finally there is Whalid (Peter Pasco), a mischievous third generation pocho who cares less about identifying with his Mexican brothers and more about whether he can afford, ironically, to take his latest date to a dinner at Applebee’s.

While they work, the men discuss whether they can afford new shoes or preschool, the stresses of family life and of having their fates determined by the whims of decisions made by those in front of the house. Undercurrents of race and class swirl around them as they work, but it’s less a black and brown issue, and more one defined by how long one has been punching his time card on this side of the border.

Although their common work bonds and unites them, their individual end goals, and the difference in the value of the dollar in the States and in Mexico, ultimately leads to a combustible conclusion that underscores the complexity of the immigration issue.

The acting is uniformly excellent, with the men forging palpable bonds that seem as strong as steel. So when the drama in the last act boils over, the audience can almost feel the stinging heat from loyalty and camaraderie betrayed.

Armando Molina’s directing is solid and keeps the action moving, while special kudos go to scenic and production designer Michael Navarro’s spot-on kitchen set.

Playwright Irwin’s experience in kitchens is obvious, and while no individual bites stand out, the overall effect of her words is memorable. Her slice-of-life piece serves to provoke a broader rumination on workers’ rights in the food industry.

As a result, it’s hard to walk away from Irwin’s searing play without thinking of the thousands of kitchens across this land where this experience plays out every day. It makes one hope that the many workers laboring in the back of the house can one day afford a life with less stress and more self-determination. Until then, unfortunately, the harsh realities of today make it so tomorrow can’t come soon enough.

Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave., Los Angeles. (323) 663-1525.

Alex Demyanenko has produced numerous television series and specials. Among his credits is the HBO documentary Bastards of the Party.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit