Labor & Economy

Under the Radar: Hospitality Workers Battle Sexual Harassment Daily

While the sexual harassment stories of high-profile women capture headlines in the mainstream media, the everyday abuse suffered by low-wage workers in the service industry has largely gone unnoticed.

According to one survey, 58 percent of housekeepers reported being sexually harassed by hotel guests, and 49 percent said that guests have exposed their genitals to them.

The man came in for dinner at the Hyatt Regency’s Tides restaurant on a Monday, the first day of his industry’s gathering nearby at the Long Beach Convention Center. Almost right away he took a discomfiting interest in the female employees, and one in particular — a busser and server named Nerexda (pronounced “Nereyda”) Soto. At first he insisted that no one else wait on him. Then he began making repeated requests — for condiments that didn’t go with any of his food, dressings he didn’t need — to lure Soto back to his table. He started asking personal questions: Does her husband make her happy? What was her sex life like? What was she doing when she got off work?

Soto says she tried to avoid him, even as he came in the next day and the next. But it was hard. When he demanded her attention, she worried that saying no risked her job. “I was new,” she says. “I thought they’d see me as a problematic employee and fire me.”

The man came in for five days straight, staying a little longer every time, Soto remembers. On the last day, he arrived at the start of her shift, stayed until the restaurant was about to close, and confronted her when she brought the check. “He gave me a slip of paper and his room key,” she says. “He said, ‘I bet you look really good outside of your uniform. Why don’t you come up and show me?’”

Soto felt “small and dirty,” she says, and, worse, responsible. “I wondered what I did that made him think he could tell me that,” she says. She worried she’d enabled him. As she watched the man head up to his room, “all I could think was that my co-workers who are housekeepers are now going to have to deal with this guy.” And those women would be working on his floor alone.

While the sexual harassment stories of high-profile women capture headlines in the mainstream media, the everyday abuse suffered by low-wage workers in the service industry has largely gone unnoticed, says Kent Wong, director of the Labor Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. “There is a heavy power dynamic that takes place in these male-dominated institutions,” he says, “where women are still not supported or believed.”

“If Gwyneth Paltrow couldn’t complain what do you want from a poor, limited-English-speaking housekeeper?”

That power dynamic may have been partly to blame when an ordinance that might have protected hotel workers recently failed in the Long Beach City Council. “One of the objections we heard [from the city council] is that there weren’t enough complaints [to spur action],” says Naida Tushnet, a former educator turned activist, and part of a Long Beach coalition that lobbies on behalf of hotel-worker rights. “But if Gwyneth Paltrow couldn’t complain, what do you want from a poor, limited-English-speaking housekeeper?”

Hotel workers are, at least on paper, protected from sexual harassment by managers or co-workers. Both Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and, in California, the Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA), prohibit employers from causing a workplace to turn hostile due to discrimination based on sex. But unless they commit actual crimes, guests and customers are another matter. “Clearly Title VII and FEHA do not cover sexual harassment by clients,” says Jennifer Drobac, an Indiana University law professor who specializes in sexual harassment law. To qualify as criminal under state and federal law, sexual harassment has to be “severe and pervasive,” Drobac explains. In Soto’s case, “The guy was a jerk and he made rude comments. He was inappropriate.” But he wasn’t outside the law.

Only if Soto had told her manager would she have triggered the law. And it wouldn’t be the customer at fault, but the hotel itself. “If she’d said, ‘Look, this guy is making my job harder, he’s keeping me at his table longer, he’s really creepy,’ then the employer could be held liable under Title VII and FEHA for failing to create a safe work environment.”

“They are single mothers. Some of them don’t speak English. They’re alone on these floors. If they yell, who’s going to listen?”

“At that point,” Drobac says, “the employer has to go to the guy and say ‘Look, my server just brought me your key card. When do you want me in your room?’”

It wasn’t just fear that kept Soto from reporting the incident at the time, she says. She literally didn’t have the words to identify what had happened to her until a few months later, when a co-worker handed her a survey. According to Soto, the hotel’s union, UNITE-HERE Local 11, “was trying to grasp how bad the problem of sexual harassment was.” (Disclosure: The union is a financial supporter of this website.) While writing up her story in the survey, it struck her that her experience belonged to a category — one that was common enough to be almost universal, but had been neglected in hotel worker and server training. “It’s so obvious,” she says. “How is it that I’ve never been trained on how to handle sexual harassment from a customer? I didn’t have any clear structure for what to do.”

In 2015, Soto joined a group of women telling their stories in a meeting with Long Beach City Councilmember Suzie Price. According to Soto, there were 14 other women present, all with stories as bad or worse than hers. Most of the women were housekeepers from a variety of hotels. One of them, Soto says, told about an incident that happened while she was cleaning the bathroom in the hotel’s gym. A man walked in, dropped the towel that covered his genitals, and blocked her from leaving. She managed to escape anyway, but in her haste left her sweater behind.

Later, the woman found her sweater on her cart, soiled with semen.

“I listened to her,” Soto says. “And I cried.”

The anecdotal accounts are borne out by data. According to an April 2016 survey of 487 female hotel and casino workers, conducted by UNITE-HERE Local 1 in Chicago, 58 percent of housekeepers reported being sexually harassed by hotel guests, and 49 percent said that guests have exposed their genitals to them. Restaurant workers, too, are on the front lines of sexual harassment battles, not least because they work for tips — a situation that forces them to influence their customers to add a few dollars onto the bill. In another survey, of 688 current and former restaurant workers across 39 states in 2014, 78 percent said they’d been sexually harassed.

“Most of the women who clean our hotel rooms are women of color,” says Soto, who has channeled her anger over her restaurant experience into becoming a relentless advocate for hotel housekeepers. “They are coming here from another country. They are single mothers. Some of them don’t speak English. They’re alone on these floors. If they yell, who’s going to listen?”

“Some companies are giving their employees whistles,” she adds. “Fucking whistles. You go blow your whistle on the 17th floor when someone’s attacking you. I’ll wait.”

Last year, Seattle voters overwhelmingly approved a landmark law, the Seattle Hotel Employees Health and Safety Initiative, establishing specific labor standards for hotel workers. In addition to lowering workloads and improving medical care for workers, the law stipulates that employers provide housekeepers, room servers and anyone else who works alone in a hotel room with a “panic button,” a small wireless device that sends a signal to security whenever a worker considers herself in danger.

It also requires hotels to post notices on the inside of guest room doors stating, “The Law Protects Hotel Housekeepers and Other Employees from Violent Assault and Sexual Harassment.” The names of guests who have been accused, in sworn statements, of violating the law will be added to a blacklist and denied service for three years.

Women’s and worker’s rights advocates, and hotel workers themselves, had long lobbied the Long Beach City Council to pass an almost identical ordinance, culminating in a September council session that rejected the law by a 5-4 vote. Lynn Mohrfeld, president of the California Hotel and Lodging Association, had warned that a blacklist of offending guests would draw legal challenges. He also argued that the provisions of the ordinance were already covered under existing law.

He’s only half right, Drobac says. It’s true that hotels are already out of compliance with existing law if they knowingly tolerate guests sexual harassing or otherwise abusing their employees. But one perfectly legal, and possibly mandatory, way of reining those guests in is indeed to refuse to serve repeat offenders — in other words, a blacklist. “If a hotel manager goes to Mr. Weinstein and says, ‘In case there’s any confusion, we want to make sure you know that the women who work here are not for your sexual enjoyment,’ and if Mr. Weinstein doesn’t get the message, then hotel has to fire him.”

Signs may not necessarily help. “You could have billboards in your lobby [saying ‘We Don’t Tolerate Sexual Harassment,’]” Drobac says. “But if the managers don’t take action, they’re meaningless.”

Absent more explicit ordinances, UCLA’s Kent Wong, too, advises hotel workers to keep the pressure on their employers using existing law. “Fundamentally, this is an organizing challenge. If more women are supported when they step forward, when they complain about being victims of sexual harassment and sexual abuse, and are given adequate remedies,” he says, “that begins to change the equation.”

He realizes it isn’t easy. “All the women who have come out against Donald Trump are still being called liars, and the president of the United States has threatened them with litigation,” he says. In the struggle to empower women to speak out, “we still have a long way to go.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

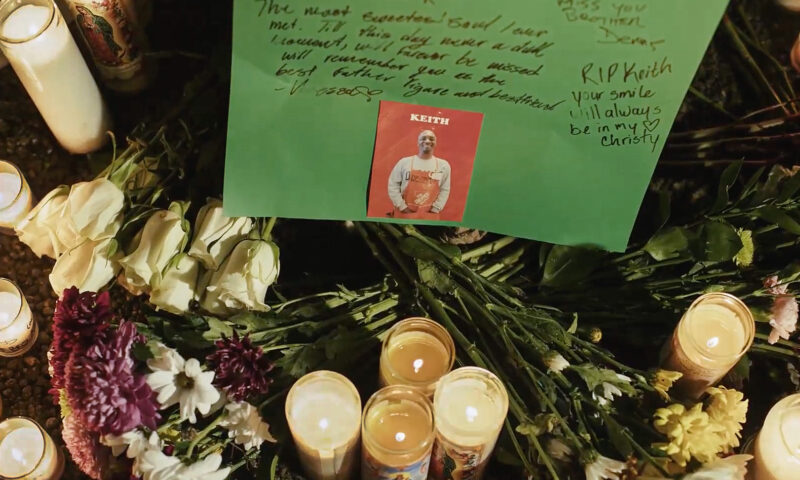

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026Can California’s New Immigrant Laws Help — and Hold Up in Court?

-

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026Keeping People With Their Pets Can Help L.A.’s Housing Crisis — and Mental Health