HEALTH

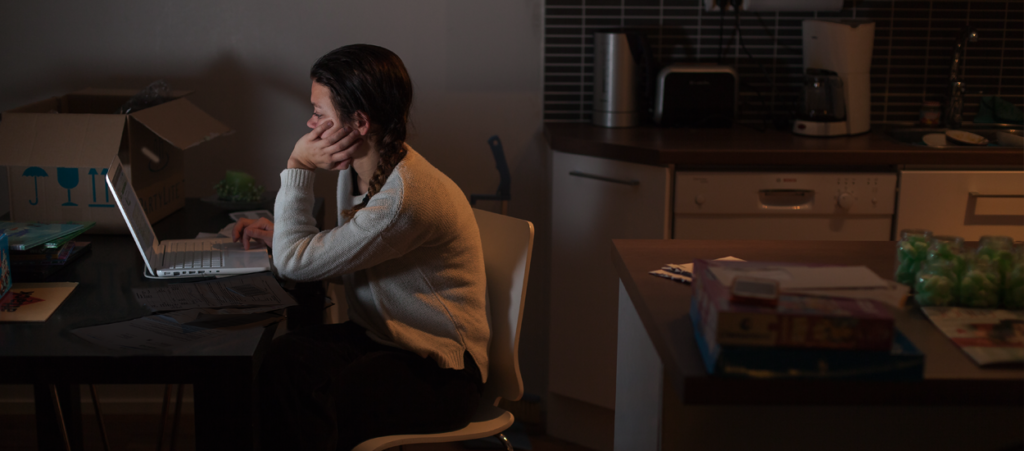

The Virtual Couch: Is Online Therapy Going Viral?

Co-published by Fast Company

Online-therapy companies are raising ethical questions about what it means to put technologists in charge of a mental health care platform with unique. Will people suffering from depression or suicidal urges be considered as patients or consumers by the new startups?

Co-published by Fast Company

A young man anxious about his career path finds renewed strength in his faith. A woman receives help dealing with the guilt arising from seeing her childhood abuser prosecuted. Another woman overcomes a breakup and learns to practice mindfulness.

These were some of the “success stories,” posted this month, on the website of Sunnyvale-based BetterHelp, one of a handful of online therapy companies that substitute the often hard-to-access office visit to a therapist’s office with a suite of web-based offerings. Billed as the world’s largest online therapy platform, BetterHelp is also turning therapy into a U.S. export, with “members” in countries around the globe.

After starting several ad tech firms, company founder Alon Matas suffered a depression that, he told Mixergy’s Andrew Warner, led him to harness his marketing prowess to advance a greater good. After all, more than 43 million adult Americans suffer from mental illness, but fewer than half reported receiving mental health services over the course of the year, according to a 2015 survey by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Many who need mental health care can’t afford it, while many regions suffer a severe shortage of mental health professionals, and even in counties rich with therapists, many people lack the time to make the visit. And there is often stigma associated with asking for help.

However, BetterHelp and its competitors are also raising ethical questions about what it means to put technologists in charge of a mental health care platform with unique privacy and safety challenges. Will, for example, people suffering from depression or suicidal urges be considered as patients or consumers by the new startups? And what does it mean for American therapists to practice their profession across cultures and international borders?

Launched in 2013, BetterHelp is growing at a rapid clip, with membership doubling “year over year,” according to Jeff Williams, the company’s senior director of business development. In 2015 BetterHelp was acquired by publicly-traded Teladoc in a $4.5 million deal, and is expected to exceed revenues of $27 million this year, according to estimates provided on a recent quarterly conference call with analysts. Two months ago, the company launched Terappeuta.com, a Spanish language version of the site.

There seems to be little doubt that BetterHelp—and firms like it—are reaching new people with their offerings, and there are some promising preliminary studies on the benefits of online therapy. However, the state of research has not kept pace with the growth of companies like BetterHelp, say experts interviewed for this story, and some therapists question the ability of clients to make real therapeutic progress in an exclusively online format.

“Not only can the client curate themselves, but they can definitely run when things get tough,” reports Loma Linda psychologist Nina Barlevy. “Of course, they can also bolt with traditional therapy, but it is far easier online.”

In the absence of face-to-face contact, Kesha Martin, a Texas-based BetterHelp counselor, has felt ill-equipped to provide the kind of support needed by her clients who had experienced trauma. “I think it’s more for people going through an adjustment — career stuff, nothing super intense,” she said. Martin, like Barlevy, is no longer actively counseling patients through the site.

Todd Essig, who is a Forbes columnist, psychologist and a relentless critic of online counseling companies, has taken particular aim at BetterHelp’s competitor, Talkspace, for allegedly exaggerating its effectiveness and sending conflicting messages as to whether it is a health-care provider or merely a platform without legal obligations for the services its contracted therapists offer.

“The problem is a confused, misleading set of messages about the relationship between therapy as it is widely understood, researched and practiced, and the text-only activities that take place on the Talkspace platform,” writes Essig.

Unlike Talkspace, BetterHelp does not offer a text only package, but BetterHelp’s terms-of-service policy also disavows responsibility for the quality of the counseling provided through the platform.

High-quality, online counseling is a viable alternative to face-to-face counseling and in some cases could lead to better outcomes,” according to the press release from the Berkeley Well-Being Institute, which released a BetterHelp-funded study in early May. The study found that 78 percent of those who reported symptoms of “severe depression” before using BetterHelp were no longer classified as having severe depression after using the service.

The study’s results are “interesting” but “not definitive” and “needed to be interpreted carefully,” in part because of deficiencies in the methodology and, in part, because the developers of a treatment typically report positive findings, writes Lynn Bufka, who is the associate director for practice research and policy at the American Psychological Association, and who reviewed the study at Capital & Main’s request.

Bufka says that online therapy shows real promise—and a feature article published on the APA website cites two academic studies supporting the benefit of an exclusively online approach—but it also raises a host of questions, including a patient’s ability to secure the privacy of their device and the ability of therapists to adequately diagnose patients remotely.

The cost of counseling through BetterHelp ranges from a relatively affordable $35 per week, to $70 per week, depending on the package selected. After completing an online form, members are typically matched with a therapist in less than four hours. They can communicate through texts, live chat, phone calls or video conferencing.

Sonya Bruner became BetterHelp’s clinical director in April and oversees a network of more than 2,000 licensed therapists who have contracts with the company. She describes an “extensive vetting process” of analysts that includes a written exercise, background checks and an interview. She worked for a year as a BetterHelp therapist to make sure the company provided a legitimate service before joining the 30-member staff.

“In some ways, having the ability to have more touch points with the person that you are working with actually enriches the therapy process,” said Bruner. With face-to-face therapy, the client typically is only seen once a week.

The “mere prospect of leaving the house” can be overwhelming or “simply unattainable” for people in severe distress, said Jay Swedlaw, a BetterHelp mental health counselor in Texas, who makes online therapy his full-time job. In these cases, having a licensed therapist on the phone can be an important lifeline. In some cases, the anonymity of the format may allow clients to open up, he adds.

He discovered BetterHelp a year and a half ago when he was making the move from Florida to Texas, and needed some transitional income. Now his work with 88 clients on the platforms of BetterHelp and its New York-based rival, Talkspace, comprise almost his entire income – about $6,000 to $8,000 a month.

Swedlaw likes the hassle-free nature of online therapy – no office, no overhead. “I can reach and help a lot more people, and that’s the most important thing,” said Swedlaw.

Some of his BetterHelp clients have been as far away as Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Europe, and they include not just U.S. citizens abroad but also residents of those countries. It could be that those seeking out BetterHelp have a strong familiarity with American culture, but, in any case, Swedlaw seemed so far undaunted by cultural barriers, which he said can “fall away” when the medium of communication is text.

“If I’m ever unsure of something, I will certainly not just guess at it,” said Swedlaw, who said he will draw on his training or do additional research.

The question of whom the platform is for remains open to interpretation. The website’s homepage directs people in crisis away from the site and toward various hotlines and other resources. Its FAQ makes clear that the service is not for people with a “severe mental illness” and also warns that BetterHelp “is not capable of substituting for traditional face-to-face therapy in every case.”

But BetterHelp by no means limits outreach to those suffering from mild anxiety or dealing with life transitions. The company provided Capital & Main with the “presenting problems” that members report on their questionnaire. The top five issues have to do with depression, stress and anxiety, self esteem, relationships, family and anger. Also on that list are bipolar, trauma/abuse and addiction issues.

The vast majority of members (81 percent) are women. Perhaps not surprisingly, about 84 percent are under 45. Forty-five percent of BetterHelp members report no history with therapy at all, suggesting that the company is, indeed, reaching new people with its offerings.

There is also the question of access for the therapist. In an emergency, a therapist in private practice would have immediate recourse to a patient’s personal information, but in an online environment the company holds that information and decides what personal information to collect. Last year The Verge published an anonymously-sourced investigative piece in which an independent contractor therapist for BetterHelp’s rival, Talkspace, alleged she was unable to contact a client whose child she believed was being endangered.

Client contact information is readily available to the BetterHelp therapists, according to Jeff Williams, “just as in the offline world,” either through the “help” page of a client’s account or through communication with the company. Either one could arrange a “wellness visit” from a local police department.

The protocol for helping an at-risk international client may be less fully developed.

“I’ve never had a crisis with an international client,” said Swedlaw, one of the more active BetterHelp therapists. “But if it did come to that point, I would just hop online and get the number for the local emergency department or try to find out if that particular country had something equivalent to the suicide hotline that we have here in the States.”

West Hollywood City Councilman John Duran and Talkspace CCO Lynn Hamilton, at Talkspace’s April conference. (J. Goodheart)

West Hollywood City Councilman John Duran and Talkspace CCO Lynn Hamilton, at Talkspace’s April conference. (J. Goodheart)

At a Talkspace conference held inside the San Francisco Jazz Center last month, its CEO, Oren Frank, seemed to push back on online therapy critics, even as the company sought external validation from the medical establishment by announcing plans to launch a randomized controlled trial –the gold standard study in which people are chosen at random to receive one of several clinical interventions.

“Every psychoanalyst above the age of 60 thinks that this is blasphemy,” Frank told the auditorium from behind a plexiglass podium emblazoned with “#workhappy.”

The subject of the gathering of venture capitalists, telehealth, pharmaceutical and human resource executives was expanding mental health care in the workplace.

Traditional therapy, Frank argued, has “not really been structured as a process that is measurable and manageable and repeatable.”

The psychotherapy profession does need to be shaken up, said Kathryn Salisbury, executive vice president at the nonprofit Mental Health Association of New York, who attended the Talkspace conference.

At the same time, she hopes to see the industry evolve in a way that integrates online therapy products and services into the health-care delivery system as a whole.

“If people are feeling in crisis or desperate,” she said, “they’ll try anything. We have a responsibility to expect new products and services [to] be evidenced-based, to be studied and proven to be effective.”

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.