Labor & Economy

The Panama Canal: Big Business’ Big Stick

About half of all U.S. container trade comes through West Coast ports. Our most important trade partners, by far, are the Asian nations. (China and Japan alone account for over half of all the stuff we import.) The West Coast ports handle the bulk of this trans-Pacific trade. And the neighboring Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach claim the lion’s share of all of this: About 40 percent of Asian imports come into the U.S. through the San Pedro Bay ports. In Southern California, we arguably sit at the single most important locus of global commerce.

And trade has largely done well for us. It is a major driver of our regional economy, swapping places every couple years with tourism as the biggest job creator. The ports generate tens of thousands of very good jobs, mainly for longshoremen. (The ports also generate many thousands of crappy jobs for truck drivers and warehouse workers, too, but that’s another story.) And throughout all of this, we’ve managed to make retailers and other businesses very, very rich. (Often at the expense of community health, but again: another story.)

But “very, very rich” isn’t good enough for most segments of the goods movement industry. They want to be richer still. And they complain about the expense of doing business in California. The environmental and worker regulations. The rules and the red tape. They look for other ways to move their containers to try to avoid “business-unfriendly” California ports. Which brings us to Panama.

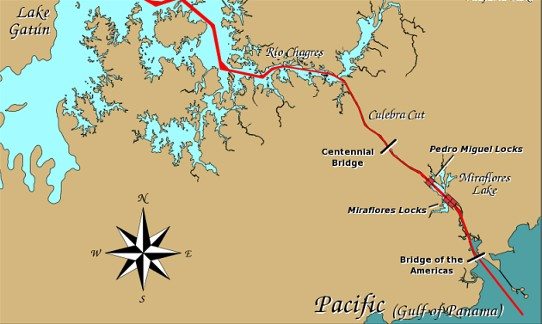

When you hear “Panama,” labor activism may not be the first thing you think of. Instead, the name may bring to mind military uniforms and a love/hate relationship with the U.S., which helped foment a revolution against Colombia in 1903 and a Panamanian secession (with U.S. warships nearby to prevent Colombian action). Panama declared independence on November 3, 1903. Two weeks later the U.S. signed a canal treaty with the new country giving the U.S. what it wanted (monopoly rights! in perpetuity!). The Panama Canal opened for business on August 15, 1914, and is considered one of the seven wonders of the modern world.

(Panamanian protests and riots in the 1960s led to a 1977 treaty that returned control of the canal to Panama in 1999.)

Being able to cut through the Isthmus of Panama has dramatically reduced shipping time and improved efficiency. While this is good for business and consumers, is it good for workers? To answer that question, we need to know a little bit about the goods movement industry.

Panama will soon celebrate the canal’s centenary and is currently in the middle of a $5.25 billion expansion project for the canal. Currently, the biggest ships that pass through its locks carry about 5,000 containers. When the expansion is complete in 2014, larger ships will be able to pass through, carrying over 12,000 containers each. This may or may not be a serious threat to West Coast dominance (experts disagree), but it is very much being used as a threat by cargo interests. “Don’t get too uppity about your environmental regulations or about workers’ rights,” they’re telegraphing, “or we’ll just go through the canal and unload our Chinese goods in Savannah, or Virginia, or Charleston, or Florida.” (All of these are in so-called right-to-work states, natch.)

Too often, our business and political leaders take these threats at face value, falling into line and making noises of obeisance, forgetting that no other ports have the infrastructure of L.A. and Long Beach, the deep harbors, the cargo-handling capacity, the experienced workers, the land for warehouses, the captive population of consumers, the proximity to Asia, the agricultural exports. We have to remain competitive, to be sure, and we are: Our ports are investing heavily in infrastructure as they clean up the air. But we don’t need to fall for business’ threats.

(In this context, the Panama Canal – a U.S. creation – has in some sense turned on us. Echoes of, yes, the CIA’s man in Panama, Noriega.)

Given all of this, I enjoyed the recent irony of thousands of canal expansion workers going on strike. The National Union of Workers in Construction and Allied Industries struck for six days, demanding unpaid back wages as well as an increase in the minimum wage. (They got their back pay and a 13 percent wage increase.) There’s something fitting about the bosses’ favorite threat turning on them, even if only briefly. It’s like the attack dog finally turning on his handler: It’s not necessarily pleasant to watch, but something about it feels right.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit