Culture & Media

The Iron Worker and The Stranger

And wisdom is a butterfly

And not a gloomy bird of prey.

— W.B. Yeats

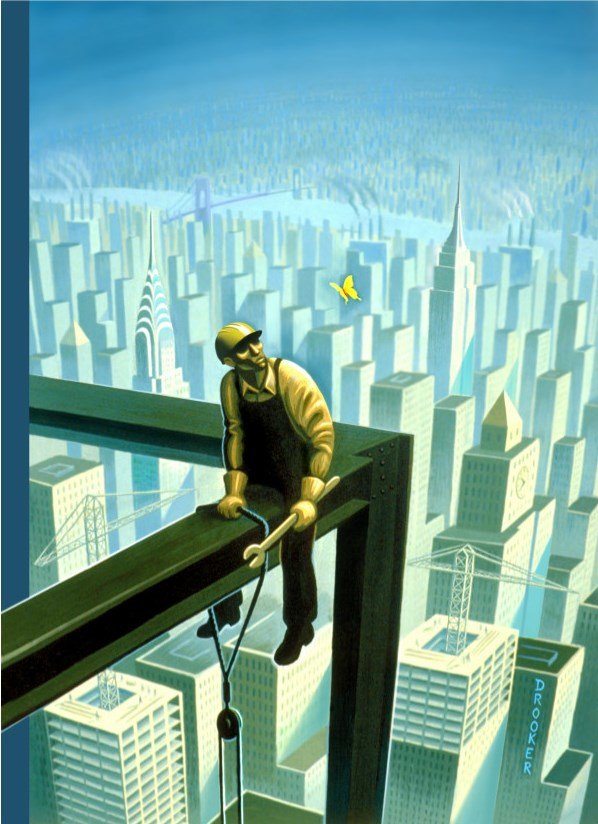

Artist Eric Drooker’s drawing of an iron worker sitting astride a steel girder looking solemnly at a butterfly is a cool image. (The drawing appeared as a 2009 New Yorker cover.) Judging from the shadows on the buildings, the sun is low in the sky. There is no sweat dripping from a grimy brow. Unlike the socialist-realist paintings of noble workers striding forward or the purposeful energy depicted in WPA murals of the 1930s, the iron worker here is alone and contemplative – sad, even.

Where are his fellow workers who might provide a release from strenuous labor with a moment of conviviality? The city itself appears quiet. The strutting, tempestuous, scandalous streets of New York do not even attract a glance. This iron worker reminds me of one of Edward Hopper’s lonely figures, only 60 stories up.

Then there is the butterfly.

In his wonderful book All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, about the sorrows and pleasures of Modernism, Marshall Berman writes about the New York that Robert Moses both created and destroyed. Berman refers to Moses as New York’s Captain Ahab, a relentless and ruthless builder of parks, bridges, highways, a “true creator of new material and social possibilities.”

He was also, Berman observes, a destroyer of neighborhoods, the planner and political architect of a brutal and at times de-humanizing “urban renewal” process. When Allen Ginsberg, in his 1955 poem “Howl” asked,

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls

and ate up their brains and imagination?…

Moloch whose buildings are judgment!

Berman and his neighborhood friends in the Bronx thought of Moses.

FDR’s Labor Secretary, Frances Perkins, said of Moses that, “He loves the public, but not as people” – he was more comfortable with an abstraction than with the living and breathing human beings who opposed his plans. His construction sites were spectacles of sight and sound, floodlights and jackhammers reminding New Yorkers that in this town, you just don’t stand still.

When French philosopher and novelist Albert Camus visited New York for the first and only time in 1946, Moses had just been named the city’s “construction coordinator” and was in the process of accumulating more power through his control of obscure commissions and boards. A black and white photo by Cartier-Bresson captures Camus in his trench coat on a New York street: collar turned up, a cigarette dangling from his mouth Bogart-style. According to New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, he was the Don Draper of existentialism.

Anticipating Ginsberg, Camus described Manhattan’s skyscrapers as “gigantic tombstones for a city of the dead.” The buildings were square prisons but also reached to the “very height of solitude,” offering a relief from the madness below.

Despite his dark imagery, Camus fell in love with New York, scorched by its “delicious and unbearable” energy, wondering if it might be another place he could lose himself in exile. He marveled at the brilliant sky over the city on a clear day. Camus was a Mediterranean man, a French Algerian alive to his body and drawn towards the sun. “I have never been able to renounce the light,” he said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

The iron worker in Drooker’s drawing sits in the sun staring in bewilderment at a delicate butterfly. They seem about to begin a conversation. How did it climb so high, this poetic symbol of intuition and refinement, the primacy of the spiritual over the material? And what about the imaginative perspective of the artist, looking down on the mystery of beauty?

The Irish poet Seamus Heaney suggested that there are certain images or poems that provoke our consciousness into “new postures,” allowing a wider scope for our own imagination. In his drawing that is also a poem, Drooker seems to be saying that the iron worker is not just a worker. He is being urged into a new way of looking at the world, becoming an interpreter of his own life. This “blue collar worker” with a melancholic face can give the spirit of beauty a new form.

Construction workers have a saying that goes “you give eight for eight” – eight hours of work for eight hours of pay. Despite the imperatives of time and labor, there are always necessary moments of repose. In the midst of his own combats, Camus demanded an occasional “respite and pause for musing,” before returning to his life tasks of working and creating dangerously.

Postscript: Eric Drooker has given me permission to use the drawing of the iron worker and the butterfly for my film Head, Hand, Heart – Craftsmanship at Work, about the building of the Wilshire Grand Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. His work and bio can be found here: https://www.drooker.com/

(Kelly Candaele is a writer, filmmaker, teacher and has served as a trustee for the Los Angeles Community College District.)

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care