Politics & Government

The Evolution of Richard Alatorre

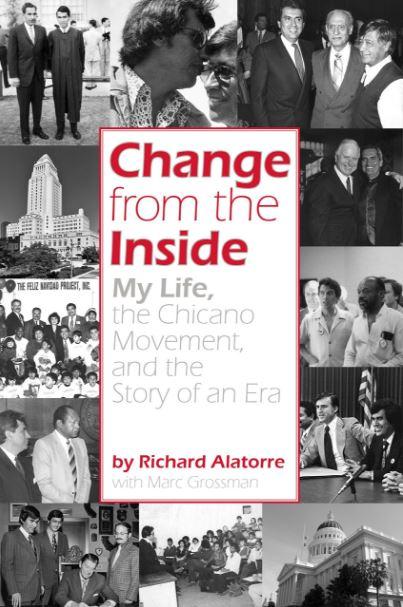

“I’m always the bad Mexican,” Richard Alatorre states early in his new autobiography, Change From the Inside. In his 12 years in the California Assembly, Alatorre powerfully supported affirmative action, better farm-worker conditions, prison reforms and redistricting. He was the man in the black hat who used Machiavellian politics to help the white hats get things done.

“I’m always the bad Mexican,” Richard Alatorre states early in his new autobiography, Change From the Inside.

In his 12 years in the California Assembly, Alatorre powerfully supported affirmative action, better farm-worker conditions, prison reforms and redistricting. He was the man in the black hat who used Machiavellian politics to help the white hats get things done. He became a bully for the progressive agenda, one whose profanity filled negotiating discourse featured his favorite threat — “I’m gonna cut your balls off.” He was Speaker Willie Brown’s right-hand man. Then he represented the L.A. City Council’s Eastside 14th District from 1985 to 1999. He did some good things there too, but he left in deep disgrace.

From his upper-working-class childhood in East L.A. to being a Sacramento heavyweight, he tells a warts-and-all story of his rise to the pinnacles of state legislative power, via a dozen years of palships, wheeler-dealing and backstabbing. During which time he seems also to have been deeply concerned with the betterment of the underserved in general, and of Chicanos in particular.

Alatorre’s autobiography, compiled with the help of Marc Grossman, is a slapdash production written in the present tense, which makes it tough to tell precisely when anything is happening. It lacks sources or notes for the many quotes it embodies — mostly fan-talk from such admirers as Brown, plus the fawnings of various subordinates. So it is nearly worthless as scholarship. Despite this, it makes for pretty interesting reading, particularly if you care about the evolution of the California Legislature from a nugatory cloister of part-timers to a full-time tribe of professional power-mongers.

And if you also want a jaded view of the rise of the biggest names in state politics, from Willie Brown to Jerry Brown to Maxine Waters to Leo McCarthy to Berman-Waxman to — well, mostly Richard Alatorre (who, in his own mind at least, was the toughest and most effective California legislator of them all), it’s all here.

Where the book comes up short is on any self-analysis, let alone insight, as to how Alatorre went off the rails after he became the first Latino L.A. City Councilmember since 1962—an immense step for local Latino political power. He did support rapid transit and a fairer city redistricting. He was generally a friend of labor, and not just by his own account. Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy co-founder Madeline Janis, who now heads Jobs to Move America, recalls of the living-wage fight in the City Council: “Alatorre was definitely helpful and very supportive when we proposed the measure in 1995 and then as we shepherded it through.”

But dark clouds overshadowed his reputation. There was his addiction, first to liquor, then to cocaine. Alatorre is frank about the havoc his dependencies caused in his career and private life. It’s nice to see that admission, even if it’s already part of the public record. But he’s in denial about the findings, accusations and allegations of pure corruption that bedeviled him in news accounts and in court well beyond his 1999 retirement.

For instance, he omits that he’s a federal felon who was sentenced to eight months of home detention after confessing to evading taxes on a $41,000 bribe. In his book, he treats this as something like acquittal. Well, it’s true he could have spent a year in prison and been fined $20,000. I guess these things are relative. In court he said he “accepted responsibility” for the malfeasance, but offered no apology.

And there is no mention of his obsession, as MTA board chief, with rigging a $65 million MTA contract for an East L.A. branch of the Metro Red Line subway in order to favor a consortium called MEC (Metro East Consultants) — 35 percent of which was firms run by perennial Alatorre cronies George Pla and David Lizarraga. Alatorre mentions favoring this subway in his book, but omits that the project was dropped due to the smell of the contract proposal. Alatorre had meanwhile arranged the firing of the MTA executive who objected to MEC. The exec, Leroy H. Graw, later collected a $300,000 unlawful-termination settlement from the MTA. In a deposition for Graw’s lawyers, Alatorre took the Fifth Amendment 108 times.

(This was not the first time Alatorre went to bat for Lizarraga and Pla, who were called the Golden Palominos on the Eastside. Usually, he was more successful.)

There were suspect deals upon suspect deals: for a downtown hotel; for an Eastside housing project; for a $100,000 donation to an Alatorre-favored charity whose events were catered by his wife. One boon companion helped buy the councilman a new house; another, Lizarraga, bought that house a new roof. The Los Angeles Times assigned two reporters to follow Alatorre’s trail but they could barely keep up. However, when he tested positive for cocaine in court, in the middle of a child custody case (he’d just sworn he hadn’t touched the drug in nine years), the bottom fell out of his career.

Alatorre mentions many enemies in his book: None is excoriated more than former 13th District Councilman Mike Woo. I asked Woo (now a dean at Cal Poly Pomona) what he felt about Alatorre now. “He was one of the most effective members of the council,” Woo allowed. “You felt he could have done anything, even run for mayor. But not after he ended up with all that baggage.”

Alatorre used his Sacramento experience to create a web of vote-trading and back-scratching, the likes of which the city had never seen. Even councilmembers who despised him used it, because it was the easiest way to get things done. As then-City Ethics Commission President Ed Guthman once told me, “He just promises you the votes [on your measure] and you watch them all go down, bang-bang-bang.” This meant more efficient council proceedings. It also meant that not many ordinances passed if they were not okay with Richard Alatorre.

On the other hand, certain ordinances that never should have come to a vote shot right through – obliging their authors to Alatorre.

All of this did not quite come to an end after he decided not to run for reelection in 1999, drawing a uniquely wide field of 14th District contenders for his old seat. Then-State Sen. John Burton got him a $114,000-a-year seat on the state Unemployment Appeals board—which dropped him after he confessed to not paying income taxes on that $41,000 bribe in 2001. He has since worked part-time for the L.A. Department of Water and Power, among other agencies, where his reputation for getting things done seems to overshadow his record of wrongdoing.

Alatorre, nonetheless, is right to assess himself as an important part of the history of rising Latino power. Journalist Luis Torres, a longtime commentator on the L.A. Hispanic scene, says: “He kicked the door open for the rest of us. He showed the way into elective politics to a generation of Latinos and Latinas. Though he crashed into the rocks, so many others followed his example and ascended.”

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit