Culture & Media

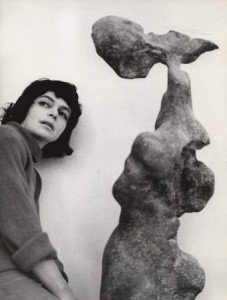

The Body Reconsidered: The Art of Alina Szapocznikow

If you’re a woman, an artist, a cancer survivor or patient; someone with a connection to the Holocaust or the 1960s women’s movement — in fact, if you’re anyone who wonders how we human beings can endure indescribable suffering and come out the other end with something to say about it – you must see Alina Szapocznikow, Sculpture Undone at the Hammer museum before it closes April 30th. I fit a number of those categories and was deeply moved to find such connections with the work.

At the beginning of the exhibit you meet the artist (who died in 1973 at the age of 47) in a rough video. She’s young and lively and seems so innocent. When the thick-headed interviewer asks about her experiences as a young girl in a Nazi concentration camp, Szapocznikow responds with “it would be immodest to discuss my own suffering.” When the same off-screen voice asks her to describe what it’s like to be a woman in 1960s Poland, she says simply, “I like being a woman.” She is not as innocent as her looks would suggest; without being rude, she easily puts off the interviewer and his insensitive questions.

The short film goes on to introduce several of her unusual humanoid pieces as they seem to parade around a Warsaw street. Many you’ll see in person as you walk through the Hammer exhibit.

Initially Szapocznikow worked in bronze, producing imposing pieces that suggest the carnage of World War II, as well as beautiful life-sized young girls on the cusp of puberty, perhaps representing herself. Later, in the post-Stalin era, she moved on to other materials, including resins, and represented women through various individual body parts, all modeled on her own. Lamps and other pieces made in the shape of lips and breasts echo the in-your-face atmosphere of the early women’s liberation movement, and I loved them.

Tragically, Szapocznikow developed breast cancer in her 40s. She brought the disease into her art: Tumors became part of her self-image, and she personalized them in her drawing and sculpture as she struggled with the disease.

In every room of the exhibit you sense the presence of the artist — her history, her body, her sufferings and her ability to physically represent and maybe exorcise them. One of the last pieces is a life-sized resin mold of her only son, genitals and all, who obviously had a trusting bond with his creative mother. At the very end of the exhibit resin molds of their faces are pressed together, flattened and mounted on the wall.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts