Politics & Government

State Senator Ricardo Lara’s Bill Says No to Wall in California

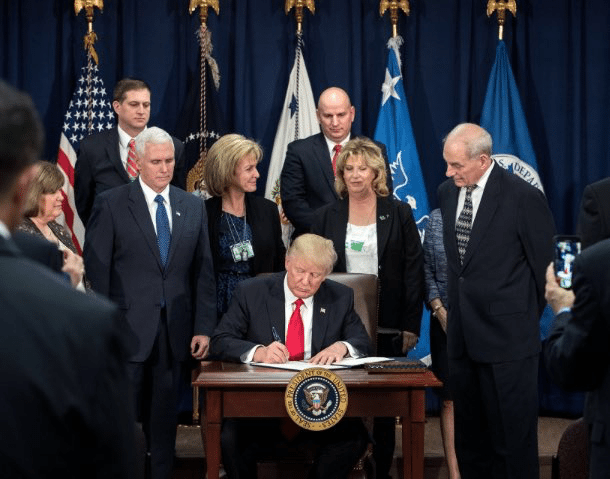

Anti-immigration decrees marked the first week of a shock-and-awe rollout of Trump initiatives to build a 1,900-mile wall along the border with Mexico, to cut off federal funds to “sanctuary cities” and to ban refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries.

Current U.S.-Mexico border fence in Texas

Anti-immigration executive orders marked the first week of the Trump administration, creating a shock-and-awe rollout of initiatives to build a 1,900-mile wall along the border with Mexico, to cut off federal funds to “sanctuary cities” and to ban refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries.

But as far as one part of Trump’s plan is concerned, the California stretch of Trump’s frontier wall won’t get anywhere if California state Senator Ricardo Lara has his way.

Last December Lara introduced Senate Bill 30, which would require California voter approval of any wall construction along the California-Mexico border. California can be harmed “in many ways” by a border wall, he told Capital & Main in a phone interview. “We know that there’s been instances where, if there’s a direct harm from the federal government to a state, the state can assert its rights to defend itself,” said Lara, a City of Commerce native whose district includes small cities in southeastern Los Angeles County.

California State Senator Ricardo Lara

California State Senator Ricardo Lara

Lara cites potential economic damage to Californians, as well as environmental harm to delicate eco-systems near the border. Much work has been done to clean up the Tijuana River and restore watersheds there, he said. A physical barrier on the California border would impede travel to Baja California, where many Californians have homes—opening up the potential for lawsuits by property owners. “There’s a lot to be considered,” he added.

“Executive order” has the ring of a clean fait accompli —the President signs a decree; governmental machinery fires up to carry it out. End of story.

Or not. Even executive orders have not-so-fine print that can bring in court rulings and the need for Congressional action that will bog them down.

The building of a wall with our third-largest trading partner remains mired in the high-profile arguments about who will pick up the check for it—a bill that by most estimates will exceed the $10 billion claimed by the president. His administrations claims that U.S. taxpayers will front the cost and await reimbursement from Mexico through a 20 percent tax on imports from Mexico. But critics say it is a plan that will cost American consumers and also land the administration and Congress in a legal and political thicket.

Still, Lara admits his legislation may not get traction. “We wanted to make sure we came out quickly with an anti-wall initiative,” he said. “Our constituents are scared and we wanted to let them know we are with them.”

As for cutting off federal funds to sanctuary cities — which include San Francisco and, in a partial sense, Los Angeles – that threat will also run up against some hard political realities.

“Carrying out immigration policy is the task of the federal government,” said Carol Sobel, who practices law in Santa Monica and was senior staff counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Southern California for two decades.

Sobel pointed to a 2012 Supreme Court decision that struck down three of four provisions of Arizona’s SB 1070, a measure that had required law enforcement to stop residents and assess immigration status. The court’s decision affirmed that immigration policy is the responsibility of the federal government.

Now it appears that the Trump White House is following in SB 1070’s steps by expanding the presence of police into the lives of immigrants. Yet it’s unlikely that a federal financial cut-off for sanctuary cities will be a matter of a swift presidential signature. Congress made the funding agreements and contracts with the cities. It could take congressional action to eliminate individual grants if the statutes authorizing their funding don’t spell out the conditions, Sobel said. “The issue is how much can you compel the state to carry out law enforcement—states have a right to decide.”

One member of a U.S. Congressperson’s staff, who spoke on background, told Capital & Main that it’s all new territory but Trump’s executive orders are now under a microscope – if analysis shows that there’s evidence that executive orders aren’t following federal law they could indeed require congressional action to go forward.

Most of the federal grants that Los Angeles, the County of Los Angeles and smaller cities receive “are not explicitly conditioned—you can’t impose conditions unless it’s in the statute” that creates the grant or local city funding, Sobel said. “A new condition of cooperation with ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] could not be imposed post hoc.”

Any funding agreements between the federal government and local jurisdictions would have to be amended by Congress to include language that that stipulates exactly what is required to receive funds—such as the demand that local law enforcement inquire about immigration status and turn the undocumented over to federal authorities. “The statute would have to be amended by Congress,” she said.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again