Labor & Economy

Santa Cruz Leads the Push for Affordable Housing

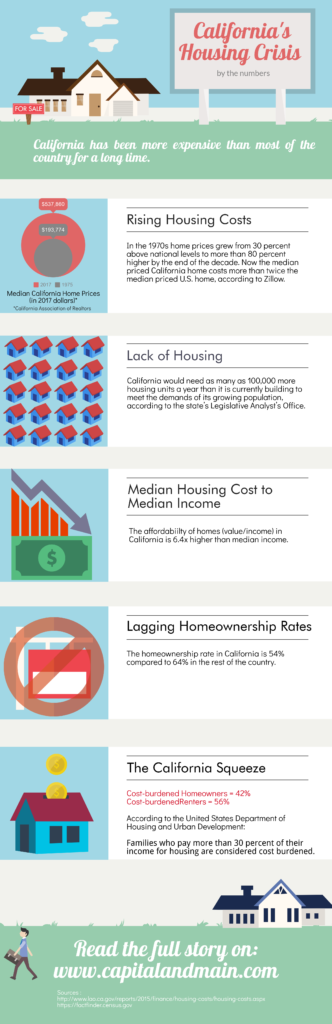

California’s housing shortage has made it difficult to be middle class and harder to be poor. Today’s median-priced California home costs more than twice the median-priced U.S. home, according to Zillow.

California has been more expensive than most of the country for a long time, but the gap became a chasm beginning in the 1970s.

John Holguin should be in a celebratory mood. He is just about to close escrow on his first house. But like too many Californians, he’s feeling a sense of diminished possibilities.

Holguin, 48, works for the Santa Cruz County Department of Public Works, striping roads and maintaining the county’s bridges and storm drains. His wife is a school receptionist, and their combined annual income of $82,000 places them squarely in Santa Cruz County’s middle class.

Yet Holguin had to withdraw from his retirement fund to afford his piece of the California Dream: a house in Watsonville, an agricultural community that has seen home prices shoot up as Bay Area tech workers and investors snatch up homes in the region.

His $3,200 monthly mortgage payment will eat up 75 percent of his take-home pay, he says. When he does retire, eight years later than planned, he and his wife will probably head for Arizona, where some of his high school classmates have already settled.

Activists and civic leaders are recognizing the extent of California’s housing crisis. They are organizing around changes to housing codes, rent control, and local and state bond measures.

Holguin’s two kids, junior college students, will help with the mortgage on the new home, but he does not expect them to remain in the state. “They know if they want to buy something, if they want to succeed, it’s not going to be here in California,” he says.

California’s housing shortage has made it difficult to be middle class and harder to be poor. But there are signs in Holguin’s home county, and elsewhere in the state, that activists and civic leaders are recognizing the extent of the crisis. They are organizing around changes to housing codes, rent control, and local and state bond measures.

At a June 12 Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors meeting, Supervisor Zach Friend suggested that residents may have “reached a real tipping point” in their willingness to support new affordable housing. He was responding to almost a dozen community, business and nonprofit leaders who spoke in support of the board’s unanimous vote that day to direct staff to prepare revisions to the county housing code to ease the way for more affordable housing development.

“It’s one thing to say that you are in favor of affordable housing,” but when a project is proposed in your neighborhood, “you can find a lot of reasons as to why you don’t support it.”

But it may take time to fix a problem that has been decades in the making, and it will certainly take political will to build and maintain affordable housing in sought-after coastal regions. Santa Cruz activists hope that Friend and other supervisors will vote this summer to place a bond measure of up to $250 million on the November ballot that could fund affordable rental housing, support first-time homebuyers, and provide housing for the homelessness.

Funding and policy changes are only the beginning. City and county officials must greenlight projects, sometimes over neighborhood opposition.

“It’s one thing to say that you are in favor of affordable housing,” Friend noted at the June 12 meeting, but when “a project actually comes forward, especially one in your neighborhood, you can find a lot of reasons as to why you don’t support it.”

California has been more expensive than most of the country for a long time. But the gap widened beginning in the 1970s when home prices grew from 30 percent above national levels to more than 80 percent higher by the end of the decade. Now the median-priced California home costs more than twice the median-priced U.S. home, according to Zillow.

Research suggests that the public “feels the pain” but is “not really enamored by some of the most obvious solutions,” says Jim Mayer of California Forward, a nonprofit organization that focuses on fiscal and government reform. “They’re really not supportive of a whole lot more homes if they think it is going to lead to more traffic and congestion, and more crime, and impact the schools.”

California would need as many as 100,000 more housing units a year than it is currently building to meet the demands of its growing population, according to the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Meanwhile, some of John Holguin’s co-workers rise in the dark to commute from Los Banos, a small bedroom community some 80 miles east. Others stay with family in Santa Cruz during the week, only to travel 150 miles home to Sacramento on the weekend. (Holguin’s 17-mile commute from Watsonville along Highway 1 will take as long as 45 minutes because of traffic.) “Only in California do we have watersheds and commute sheds,” says Mayer.

“My parents bought their first place at 25, and I’m 48,” Holguin notes. “To me it seemed like they had it easier back then.” He’s right about his parents’ generation of homebuyers. Back in 1975, the median home price in the state was $193,774 (in 2017 dollars). Last year, according to the California Realtors Association, it was $537,860 — nearly three times that much.

Of course, Santa Cruz is a particularly pricey slice of the California real estate market. Its sun, surf and scenery draw tourists, as well as tech industry workers from “over the hill” in Silicon Valley, who have money to spend. The median price for a single family home in Santa Cruz County shot up to $935,100 in March, a record high, the Santa Cruz Sentinel reported.

Santa Cruz County is home to lower-wage agricultural and service industries, making affordability a particular challenge for those who work there. Also, local redevelopment agencies, one of the few funding sources for affordable housing available to local governments, were eliminated in 2012, contributing to the housing shortage across the state.

Small-town Santa Cruz also faces pressure from its University of California campus, whose chancellor announced plans last fall to increase its student body by as many as 10,000 students by 2040. In a sign of voter frustration, the city of Santa Cruz approved a non-binding measure opposing the university’s growth plans by a margin of 76-23 percent.

And then there is the resistance on the part of some residents to accommodate growth. Some simply want to “preserve the open space and restrain the growth” as much as possible, says Don Lane, one of the leaders of Affordable Housing Santa Cruz County, a local coalition that is advocating for a housing bond measure to be placed on the November ballot. “But you’ve just got all this high-priced housing, and it’s still crowded, and traffic is still getting worse.”

Lane, a former mayor of the city of Santa Cruz, says denser “infill” housing in commercial corridors will lead to a more efficient and effective use of space without compromising the region’s preservationist traditions.

The plight of Santa Cruz’s middle-income residents is not as dire as that of its poor, of which there are many. The county has among the highest poverty rates in the state. Farmworkers live in overcrowded and sometimes dangerous conditions. At the June 12 board meeting, Ann López, the director of the Center for Farmworker Families, relayed an instance of 16 people living together in a home of less than 1,000 square feet.

Matthew Nathanson, a public health nurse with the county, was motivated to advocate for an affordable housing ballot measure after witnessing the clients he serves “falling into homelessness” because of their inability to afford rent. The median rent for a two-bedroom home in Santa Cruz was $2,450 a month in May, a 4.7 percent increase from a year ago, the Santa Cruz Sentinel reported.

Nathanson, who is also a regional vice president with Service Employees International Union Local 521, says that housing has become a central issue for city and county workers like Holguin, who are becoming increasingly difficult to recruit. Road workers who are on call during the rainy season need to live “within a reasonable distance” of their jobs, he adds. And pay increases won at the bargaining table risk being “all wiped out” by the cost of housing.

The measure, which would require a two-thirds vote of the public, would be paid for by commercial and residential property owners, according to Lane. The original proposal was for $250 million, but he says the bond measure is now “looking more like $150 million” and could benefit between 1,500 and 2,000 households.

The campaign was inspired by the success of housing measures in Alameda and Santa Clara counties, he says. Another $4 billion housing measure will be on the state ballot this November.

Still, once the funding is in place, the projects will need to get approved by local governments and built. The bond measure proposed for November is only one piece of the puzzle, according to Nathanson.

“It took us a long time to get into this situation,” he says. “I think there is a shift going on, but it’s going to be a struggle.”

Research assistance provided by Jake Conran.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care