Labor & Economy

Saint Dorothy Day?

In his speech to Congress, Pope Francis praised Dorothy Day — along with Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Thomas Merton — as one of four “representatives of the American people” whom he admired.

Pope Francis was probably the first pope to mention Day’s name in public. It is unlikely that anyone else who addressed Congress in the past had uttered her name.

No doubt most members of Congress — and most Americans watching the speech on television or listening on the radio — had never heard of her. Many of them would have had to Google her on their iPhones and tablets. Some of them — like House Speaker John Boehner, the arch-conservative who invited Pope Francis to speak to Congress — might not have been pleased with what they discovered.

Day (1897-1980) founded the Catholic Worker movement on the principles of militant pacifism, radical economic redistribution, and direct service to the poor. She influenced generations of activists through the movement’s newspaper, the Catholic Worker, and through Catholic Worker hospitality houses located in urban slums around the country, which provide food and shelter to the destitute.

In a 1971 interview, Day described her philosophy:

“If your brother is hungry, you feed him. You don’t meet him at the door and say, ‘Go be thou filled,’ or ‘Wait for a few weeks, and you’ll get a welfare check.’ You sit him down and feed him. And so that’s how the soup kitchen started.”

But Day and her comrades thought that direct service was inadequate. They wanted to change the economic system, not just provide charity to its victims. She became an organizer and an activist, a regular presence at demonstrations and rallies, and an advocate of civil disobedience, attested by her own lengthy arrest record.

Day was a constant critic and a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church. The church’s hierarchy marginalized her for her radicalism.

“Don’t call me a saint,” Day once said, “I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” But for many years, some of Day’s admirers have nevertheless urged the church to canonize her for her lifetime of social and spiritual activism. That campaign got a boost three years ago when the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, at the suggestion of conservative New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan, voted unanimously to endorse her canonization, even though she had an abortion as a young woman. On Thursday, Pope Francis seemed to be taking up the cause.

“In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement,” the Pope Francis said on Thursday. “Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.”

Was this Papal shout-out Francis way of encouraging Day’s elevation to sainthood?

Although Day and Pope Francis share many views in common, few people who knew her in her youth could have predicted that she might one day be a candidate for canonization.

She was raised in a bookish family, nominally Episcopalian but not religious. The Days moved around the country as her father, a sports reporter, pursued jobs. When she was a teenager, the family lived in Chicago. Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle — about the miserable conditions in the city’s slums and meatpacking plants — inspired her to take long walks in Chicago’s poor neighborhoods. Her brother, Donald, who wrote for a progressive newspaper, the Day Book, encouraged her to learn about radical politics. She read about socialist union organizer Eugene Debs, the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies), and the Haymarket anarchists. She was drawn to the ideas of anarchist Peter Kropotkin.

In 1916 Day dropped out of the University of Illinois after two years and moved to New York City, where she got involved in bohemian and radical circles. The chain-smoking Day looked for a job as a journalist, but none of the major newspapers would hire a woman reporter. Undeterred, she convinced the editor of the Call, a socialist paper, to pay her $5 a week. Day covered strikes and peace meetings and even interviewed Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary. (He was so critical of American Socialists that Day’s editor gutted the piece.) Day later wrote for other Socialist publications, including the Masses and the Liberator.

In November 1917 Day was one of forty women arrested and then briefly jailed during a rally in front of the White House to protest the brutal treatment of imprisoned suffragist Alice Stokes Paul. After they arrived in prison, Day and other women launched a hunger strike and were eventually freed by presidential order. It was the first of her many arrests.

As a young woman, Day rejected the sexual mores of her time. She became pregnant and had an abortion, a decision she deeply regretted, which she described in her semi-autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924). For the rest of her life, she ardently opposed abortion.

In 1924 she fell in love with botanist Forster Batterham, an atheist and anarchist who was opposed to marriage and to having children. They lived together for four years. When she became pregnant again, she was ecstatic, but Batterham opposed her decision to have the baby. Their daughter, Tamar, was born in 1926.

Day was a religious agnostic, but she occasionally attended services at Catholic churches, which she viewed as the churches of immigrants and the poor. Tamar’s birth triggered a spiritual epiphany that led her to officially join the Catholic Church the next year. Gradually, her relationship with Batterham fell apart as Day grew increasingly religious.

Initially, Day felt like an impostor, embarrassed at not knowing the proper rites. But her religion soon became her foundation, with prayer and Mass an important part of her daily life. In explaining her conversion later, she wrote, “My very experience as a radical, my whole makeup, led me to want to associate myself with others, with the masses, in loving and praising God.”

Day began to write for liberal Catholic publications such as Commonweal and America, where she fused socialist ideas with Catholic social teaching. In 1932 Day visited Washington, DC, to cover a hunger march sponsored by the Communist-led Unemployment Councils. She felt herself drawn to the dispossessed marchers. She wondered why the Catholic Church was nowhere to be seen. “Is there no choice but that between Communism and industrial capitalism?” she wrote. “Is Christianity so old that it has become stale, and is Communism the brave new torch that is setting the world afire?”

That year Day met Peter Maurin, the man who would set her on her path. She called him “the French peasant whose spirit and ideas would dominate the rest of my life.” Like Day, he was a journalist and a convert. He had heard of Day through the editor of Commonweal and he sought her out, offering to mentor her in Catholic social teaching. She later wrote that Maurin was “a genius, a saint, an agitator, a writer, a lecturer, a poor man, and a shabby tramp, all in one.” He also was a compulsive talker who never stopped “indoctrinating” Day, as he put it, and anyone else who would listen.

Through Maurin’s teaching, Day began to embrace the idea of poverty as a way of life, sharing with others, paring away material goods, and creating a community based on Christian love. Maurin envisioned an action program that included a newspaper, roundtable discussions, hospitality houses, and agrarian communes.

With virtually no seed money, Day launched the Catholic Worker newspaper, publishing the first issue on May 1, 1933. She assembled the tabloid at her kitchen table and had 2,500 copies published by the Paulist Press for $57. She and some friends hawked the paper to passersby in New York’s Union Square for a penny a copy.

Her timing could not have been better. It was the midst of the Depression, and a newspaper aimed at the downtrodden — radical but not doctrinaire — had plenty of appeal. Within a few months, the print run had increased to 25,000, and it rose to 110,000 within two years. In addition to addressing labor issues, the Catholic Worker tackled other topics that the regular Catholic press would not touch, including racism, lynching and corporate greed.

As the newspaper attracted a following, Day and Maurin sought to put their principles into practice. In 1933 Day, Maurin, and a small group of followers launched the Worker School, followed by the first Catholic Worker house in a Harlem storefront. They soon rented an apartment with space for 10 women, and then a place for men. The Catholic Workers continued to participate in direct action as well as service. They picketed the German consulate in 1935 to protest the rise of Nazism, walked picket lines with striking workers, and helped on breadlines. They also attempted to launch a garden commune on Staten Island as a sanctuary for people living in New York’s tenement slums. However, the project was unsustainable, in part because many who made their way out from the city had little interest in hard manual work.

In 1936, they moved into two buildings in Chinatown and opened them to house the poor. The staff of these “hospitality houses” (who received only food, board, and occasional pocket money) did not try to convert their guests to Catholicism or radicalism. They imposed no conditions.

Although many in the church welcomed or at least tolerated the Catholic Worker, others were appalled, in part by Maurin and Day’s acceptance of any poor person who needed help, no matter his or her background or circumstances. Day’s strong personality was called “dynamic” by admirers and “domineering” by detractors. She believed not in majority rule but, rather, in inspiration by take-charge visionaries. Day never knew how she would pay the bills, but she had faith that donations would arrive, which they usually did.

By 1936 the Catholic Worker movement had opened 33 hospitality houses around the country. The houses all had “colorful and slightly mad characters who drifted in to partake, more or less permanently, of Worker hospitality,” according to William D. Miller’s biography of Day, A Harsh and Dreadful Love.

As a young radical, Day rejected war as serving only capitalist interests, pitting workers from different nations against each other. After her conversion to Catholicism, she remained a pacifist, based on her interpretation of Gospel teaching — but her stance was often contrary to the views of the Catholic Church.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War tested her pacifist views. Most leaders of the Catholic Church supported the fascist general Francisco Franco, seeing the battle as one of Christianity versus communism. Day received a great deal of hate mail when she refused to take sides in the war because of her pacifist beliefs. But Day viewed Franco as Adolf Hitler’s ally and was one of the founders of the Committee of Catholics to Fight Anti-Semitism.

Animosity toward her pacifism grew stronger as the United States prepared to enter World War II, which Day opposed. Circulation of the Catholic Worker dropped dramatically–from 190,000 in 1938 to 50,500 in 1946. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover considered charging Day with sedition after the newspaper published an article, “Forget Pearl Harbor,” referring to the Japanese bombing of Hawaii. She opposed President Truman’s decision to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

In the 1950s, her strong antiwar stance led her to oppose civil defense drills, which she believed duped people into believing nuclear war was survivable. She and other Catholic Workers sat on park benches when ordered to take shelter, and for this she was arrested three times and once sentenced to a month in jail.

Day actively opposed the Vietnam War, and she was close to Daniel and Philip Berrigan, both Catholic priests, when they were jailed for draft resistance. In 1973, when she was 76 and in failing health, she traveled to the San Joaquin Valley in California to demonstrate with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers union. Along with a thousand others, she was jailed — for the final time.

Day’s writings, especially her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, and activism have inspired several generations of social change crusaders. She influenced the Berrigans, Cesar Chavez, and Michael Harrington, who was a Catholic Worker member for several years and whose 1962 book, The Other American, led Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to launch a war on poverty.

Over the years, thousands of Americans have participated in the Catholic Worker movement and helped build support for civil rights, environmental, anti-poverty, labor, and other progressive causes. Catholic Worker members and ex-members were deeply involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement that began in New York in 2011 and spread quickly throughout the country. The Catholic Worker movement remains a small but vibrant voice for social justice.

The Papal shout-out will certainly renew interest in Dorothy Day’s life and legacy. By embracing Day, the Pope rankled conservatives within and outside the Catholic Church, including Rush Limbaugh, who went ballistic against the Pope and Day during his radio show on Thursday. How ironic, then, that Francis’ carefully-chosen words may soon elevate the radical Day to a place among America’s saints.

This article is crossposted from the Huffington Post with permission.

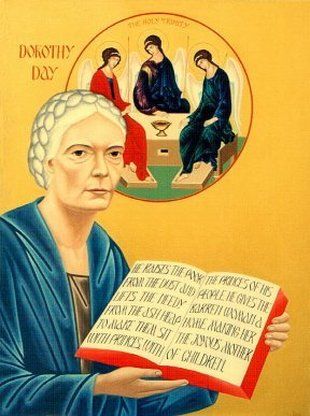

Dorothy Day icon by Nicholas Brian Tsai

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care

-

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026

Dirty MoneyFebruary 20, 2026As Climate Crisis Upended Homeowners Insurance, the Industry Resisted Regulation