Pandemic Nation

Remote Communities Face Virus With Fewer Hospitals

The lights are going out in America’s rural hospitals and clinics at the moment they are most needed.

As the early waves of the novel coronavirus pounded New York and California, one body of thought was that rural America, more remote and physically distanced by definition, might be spared the worst of the infection’s global spread. Instead, COVID-19’s strong expansion to nonmetropolitan areas in the South and Midwest has dragged a festering national health care problem back under the spotlight.

Across the U.S., rural hospitals and medical centers are folding at an alarming rate, leaving patients, many of them lower income, scrambling to find adequate care at a critical time. And while there are plenty of reasons why a remote facility might be in dire straits or shut down altogether, a decade’s worth of research points to at least one consistent truth: States that have refused to expand Medicaid coverage through Obamacare are seeing their hospitals close at the highest rates in the country.

75% of 216 surveyed hospitals found to be “most vulnerable” to future closure were in states that chose not to expand Medicaid.

A recent report by the Chartis Center for Rural Health noted the grim findings. Last year, the worst for rural hospitals since the research group began tracking data in 2010, 19 such facilities closed. There have been 34 closure announcements in the past 24 months, and 120 shutdowns in a decade.

Of the eight states that have seen the greatest numbers of closures in that span, the report’s authors said, “none are Medicaid expansion states.” The list includes Texas, with 20 rural hospitals shuttered since 2010, Tennessee (12), Oklahoma (7) and Georgia (7).

Each week Pandemic Nation offers a roundup and analysis of news about the coronavirus. Please send feedback and related tips and announcements to mark@markkreidler.com

Regional hospitals in less populated areas of the U.S. have been struggling to stay above water for years, and the Chartis report suggests that about a quarter of them currently show signs of imminent financial crisis. But some facilities have been able to remain in business thanks in part to the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of the number of Americans eligible for Medicaid.

The expansion allowed hospitals which serve poorer people, as many rural ones do, to be reimbursed more often for the care they provide. While the Medicaid reimbursements don’t always cover the full cost, they reduce the number of purely uncompensated cases – a huge problem for many rural facilities.

But individual states had the option of whether to participate in the expanded Medicaid coverage – and 14 of them said no. Does it matter? Well, the Chartis report found that a rural hospital has a 62 percent lower chance of closing if it’s located in a Medicaid expansion state. Of the 216 hospitals the researchers found to be “most vulnerable” to future closure, 75 percent were located in states that chose not to expand Medicaid.

According to a data brief from the RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis, “A small number of [coronavirus] cases creates stress for low-capacity systems just as a large volume of cases creates stress for larger capacity systems.” That’s to say nothing of those rural areas where the regional “low-capacity system” has closed its doors.

* * *

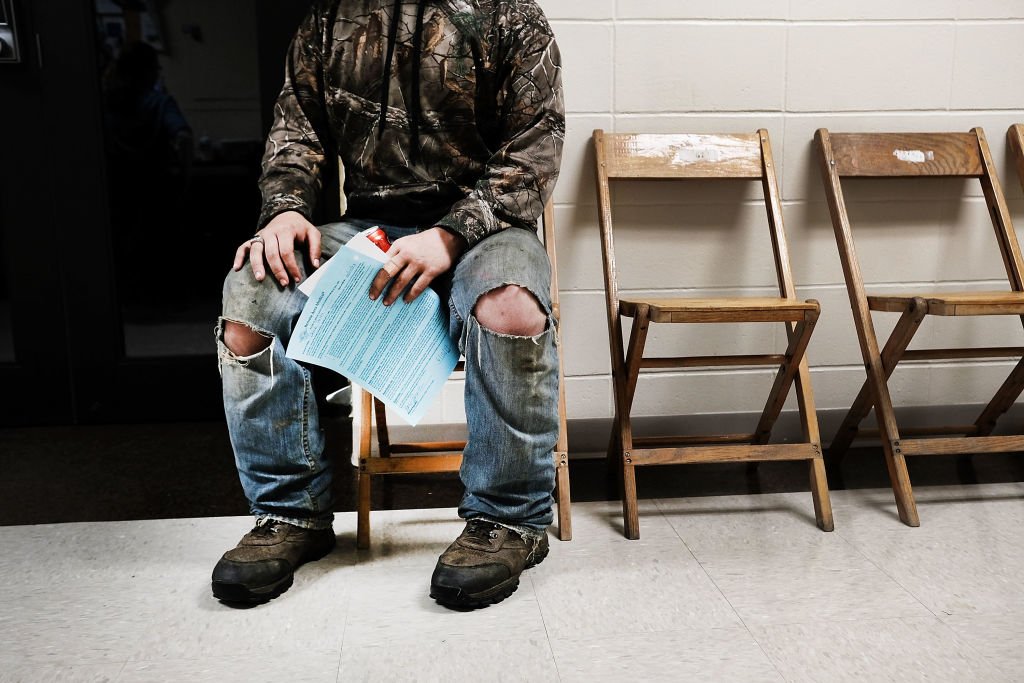

Those who earn the least in America can least afford to lose the jobs they do have. But according to a supplemental survey recently conducted by the Federal Reserve, that’s precisely what is happening.

Survey: More than a third of households cannot pay all of their current month’s bills in full.

The survey found that one in five U.S. workers lost their jobs in March and early April. But among households earning less than $40,000, which includes many families with workers in hourly-wage and service-economy jobs, the newly unemployed figure nearly doubled, to 39 percent.

The Fed sought to supplement its annual report on economic well-being in America because the initial report was prepared before COVID-19 reached the U.S. Its findings were delivered last week, at the same time that another 3 million people filed for unemployment benefits. That brings the total number of first-time jobless claims to 36.5 million since mid-March.

Among those who’d recently lost jobs, the supplemental survey found, more than a third of households could not pay all of their current month’s bills in full. Less than half said they could pay for a $400 emergency with cash – regardless of their annual income levels.

* * *

Free health care for all has been a difficult sell in the U.S. in the best of times. How about during a pandemic?

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) last week introduced the Health Care Emergency Guarantee Act, which would “eliminate all out-of-pocket health costs for every person in America during the COVID-19 crisis,” according to a release from his office.

“No one in this country should be afraid to go to the doctor because of the cost – especially during a pandemic,” Sanders said.

The Senate legislation had six co-sponsors, including Sens. Kamala Harris (D-California) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). It drew the support of dozens of national organizations and unions, including National Nurses United, the largest union and professional association of registered nurses in the country.

* * *

After long waits and brutal supply shortages in several states, COVID-19 testing is beginning to roll out on a broader scale across the country. But lack of access in the poorest neighborhoods is one reason – among others – that the tests may be slow to reach those who need them the most.

Surgeon: “We know there’s a lack of trust in the African-American community with the medical profession.”

Using data from 20 states that provided detailed information, the Washington Post found that few are testing at their full capacity. In some cases, lack of equipment is still the primary obstacle. But in others, mistrust of the system and a lack of mobility in the process are proving just as significant.

“We know there’s a lack of trust in the African-American community with the medical profession,” Ala Stanford, a pediatric surgeon in Philadelphia, told the Post. Stanford created a program to provide free testing in low-income and minority neighborhoods, using church parking lots to reach more than 3,000 patients in the past few weeks. “You’ve got to meet people where they are,” he said.

Another contributing factor: The criteria for getting a test were so restrictive at the outset that many people still assume they’re not supposed to try unless they’re already very sick. Although state and federal officials have been relaxing those guidelines, it may take a while before the message gets through.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts