In his first term, Trump promised to build new roads, bridges, airports and railways.

This time he seems more invested in tearing things down.

By Erin Aubry Kaplan

Remember Donald Trump, the champion of national infrastructure?

Amid his outsized fixations — making immigrants the bane of the country and bolstering tax cuts for the rich — it’s easy to forget that during his first term, the man who made his name as a private developer repeatedly promised to fix the nation’s “crumbling infrastructure.” He promised to do far better than the first GOP “infrastructure president,” Dwight Eisenhower.

Between 2017 and 2019, Trump proposed spending as much as $2 trillion to upgrade America’s roads, bridges and airports. He sought bipartisan support for massive projects that, he insisted, were “essential” to keeping America great. For a brief moment, it seemed possible for Trump to shamelessly promote himself as president and do some good for the country.

Alas, Trump proved to be too distracted by his own lack of focus, infighting in his administration and controversy around his relationship with Russian leader Vladimir Putin. During repeated “Infrastructure Weeks,” Trump would invariably make plenty of non-infrastructure news, overshadowing and undermining whatever constructive efforts his government had in mind. By the time the COVID pandemic hit during the last year of Trump’s presidential term, the White House essentially gave up on any big buildout, or any buildout at all.

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

Ironically, while the career businessman didn’t become the Infrastructure President in his first go-around, the career politician — Joe Biden — did. He signed legislation that wasn’t just historic for its $550 billion infrastructure price tag, but also for its larger vision and ambition.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 was intended to modernize the nation’s energy, broadband internet, bridges, roads and more, while requiring that nearly half of it would be built in underserved communities where the need was historically greater. Infrastructure and social equity would get dramatic upgrades at the same time.

Now, six months into Trump’s second, much more partisan and increasingly authoritarian presidency, he has shown little to no interest in either. His second-term obsession with snuffing out diversity, equity and inclusion has translated, since retaking the White House, in the prompt cancellation of the equity provision, known as Justice 40, in Biden’s infrastructure legislation.

As for the projects created by that legislation, he paused funding and took down the website Invest.gov, which had been providing states with updates on them. Those projects are now endangered by Trump’s other new obsession — erasing all things Biden and “big government” in general.

His aspirations as a can-do developer for the nation have been replaced by his determination to accumulate more and more power; he’s thus far been more focused on making his legacy about tearing things down, not building them up.

And yet the twinned mission of equity and infrastructure is not dead, though like the people involved in a lot of efforts at social change, the people intent on that twinned mission are trying to figure out a way to proceed in a suddenly hostile environment.

Take the Equity in Infrastructure Project Pledge. When the Infrastructure Act passed in 2021, dozens of local governments, transit authorities, water and port authorities and financial institutions involved in infrastructure came together to commit to growing diversity in federal contracting, which was vastly expanded by the legislation.

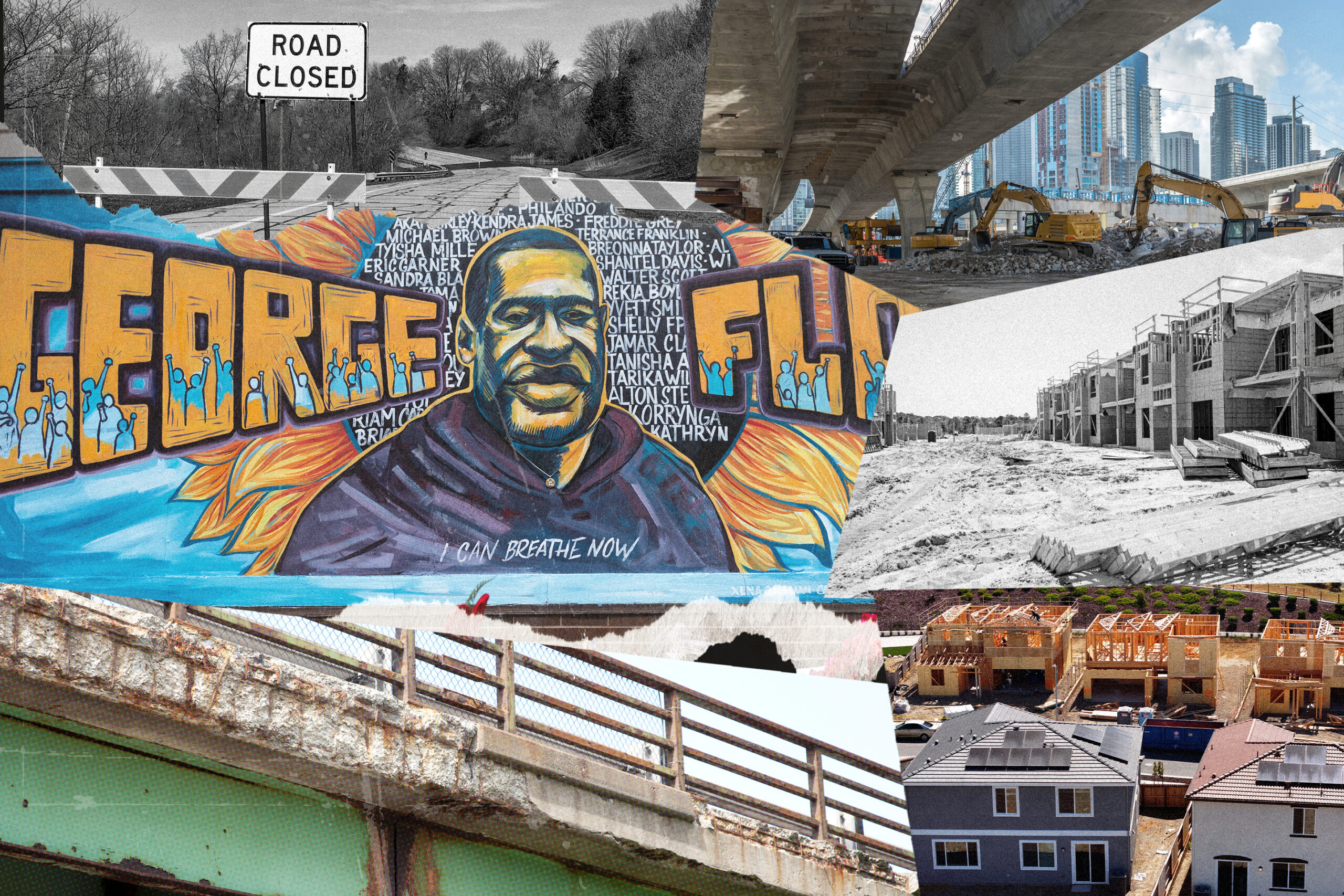

This was also in the wake of the George Floyd movement, when the country was still contemplating specific ways to achieve greater racial justice on as large a scale as possible. With its focus on diversifying federal contractors in infrastructure work that would take years, the pledge was answering that call. The Equity in Infrastructure Project, described as a “coalition of the committed,” is rooted in California but has members in states including Colorado, Illinois and Kansas.

And despite Trump’s return to power, its numbers are growing: In April, the EIP Pledge announced 17 new signatory agencies in the preceding nine months, bringing membership to a total of 91. That’s a 33% increase from 2022.

But that growth has come with a softening of once-bold language about aiding the mission of racial justice and historical redress. These days, EIP is touting equity as economic common sense. In a January statement, it called itself an “economic development organization” creating opportunities for “historically underutilized businesses.”

The argument is that bringing small, capable but less experienced businesses into the traditionally big business-dominated federal contracting pool heightens competition and lowers costs, which saves agencies — including parts of the federal government — money.

What’s not to like? Project member Ingrid Merriwether called it a no-brainer. Merriwether is African American and president and CEO of Merriwether Williams Insurance Services, an insurance firm serving Los Angeles and the Bay Area that specializes in helping small businesses, especially minority and women-owned businesses, qualify for public contracts.

Navigating around hostile political realities to pursue diversity goals is nothing new for her, or for California. She launched her insurance firm in 1997, a year after the passage of Proposition 209, the landmark California state initiative that banned affirmative action in college admissions and public contracting. Despite the political headwinds, Merriwether has diversified contracting by facilitating $1 billion in small business bonding — to provide guarantees that a business will fulfill its contractual obligations — over the last 28 years. Of all the small businesses she’s helped into the big leagues of federal contracting, only two failed to complete their projects — a failure rate of less than one-tenth of 1%.

She expects the EIP Pledge project will reproduce that kind of success exponentially. Only 5% of federal contractors are Black and a similar percentage are women. The needle hasn’t moved much in the three and a half years since the Infrastructure Act passed, though the door to opportunities was more open than it had ever been.

Keeping that door open is essential, Merriweather said, for small businesses but also for communities where those business owners work, live and spend money.

Generating those “economic multiplicative effects” is why Merriwether said equity, however much it’s demonized, remains the pledge’s focus.

Maintaining that focus has become the real, sometimes surreal fight in Trump 2.0, especially for such a high-profile effort involving so much public money. Toks Omishakin, California’s secretary of transportation, recently declined an interview about the Pledge but said in an emailed response that since 2022, the state has set record levels for small business participation via mentorship and other programs. He added: “We must move from symbolic to systemic efforts — every single person deserves the chance to be successful.”

Merriwether pointed out that “every single person” does include white-owned businesses that, despite their historical advantages, also need help competing with big-money firms. In other words, the Pledge practices the kind of across-the-board diversity that even MAGA should find hard to oppose. Besides increasing profits, Merriwether added that another huge benefit of bringing smaller businesses into big projects is that it creates a sense of shared risk and investment in a successful outcome for all.

“It really changes the dynamic of the whole project,” she observed. At this moment, that’s a powerful idea.

But evidently not for Trump. Last month, his Department of Transportation announced a new infrastructure initiative, a $488 million grant program focused mostly on improving roads and bridges in rural areas. It’s a modest redux of Trump’s first-term plan, far less ambitious than Biden’s, most notable for stripping out all the equity provisions Biden saw as essential. This time around it’s called Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development — BUILD for short. What actually gets built in the era of MAGA remains to be seen.

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main