Culture & Media

One World Trade Center: More Than Ground Zero

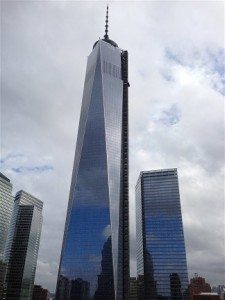

The construction elevator of One World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan is attached to the outside of the 104-story tower. From the ground it looks like a giant zipper, moving slowly up and down as the car, filled with workers and their tools, makes the six-minute, 1,776-foot journey from ground level to the top. (The building’s height was purposefully designed to match our year of independence.)

Riding up in that elevator to the 103rd floor recently, I kept myself a safe distance from the steel gates that protect you but also, unfortunately, allow you to see how high up you are hanging in space. I had to “man up” just to step into the metal box.

Phil English, a shop steward at the tower for LIUNA (Laborers’ International Union of North America), one of several unions that have members working to complete the tower, rode up with me. (See LIUNA World Trade Center videos here.) He laughed when he said he wanted to ride on the window-washing contraption attached to the outside of the top floor.

“I just want to go on it once,” he tells me. “To look down from that height and see how it feels to be hanging on the outside of the building.” I inched away from the elevator doors and thought of Bruce Springsteen. The title song from his album, The Rising, captures the tragedy and pathos of what happened 12 years ago on September 11 better than any speech I have heard about that day:

Sky of blackness and sorrow

Sky of love, sky of tears . . .

Sky of memory and shadow

Your burnin’ wind fills my arms tonight

Sky of longing and emptiness

Sky of fullness, sky of blessed life

A great song called forth from a great tragedy. If your commemorations demand something more than silence – which is my preference – then it’s not a bad choice.

I’ve been on many construction sites over the years and for various reasons. But I’ve never been on one where there was such a palpable sense of enthusiasm and pride. The workers I spoke with over three days on the site had no confusion about the importance of what they were doing. Each one of them felt as though they were contributing to something historic.

“Even the people on the street thank us for doing this when we go on coffee break,” Laborers’ Local 731 member Marcos Goncalves said during an interview. “I say it’s our job but I am proud of it.”

Clint Jones, another Laborers’ Union member, and who is from Guyana, came to Ground Zero three weeks after the Twin Towers fell to work on the cleanup operation.

“There was the smell of death,” he said. “But we had to get the job done.” Jones expresses a common feeling that the rebuilding is a sign of resilience and strength: “We are letting the world know we are back.”

The experiences and emotions of Goncalves and Jones are common ones. The building of “Freedom Tower,” as it was known before being “officially” designated as the more symbolically benign One World Trade Center, has been a repository for people’s desires, belief systems, emotions and politics ever since the discussion began about what would replace the Twin Towers.

While everyone in the debate agreed that the “sacred space” of Ground Zero should be neutral and apolitical, that belief itself generated fierce conflicts over what counted as political. As Elizabeth Greenspan points out in her new book, Battle for Ground Zero: Inside the Political Struggle to Rebuild the World Trade Center, the site quickly became a loud public square that everyone felt they owned a piece of.

If the story of what ultimately ensued at the 16-acre site is about the resilience and power of the owners of some very valuable corporate real estate, the story is also about democracy and what happens when people without a leasehold on property feel that they are nonetheless entitled to determine its function and meaning.

The tension between private and public, capitalism and democracy, is all the more relevant in the case of Ground Zero, given the site’s history. The original World Trade Center was the product of a public-private partnership largely initiated by banker David Rockefeller, who had a vision of an expanded international financial center in Lower Manhattan. He needed government assistance and got it.

Legislation drafted by his brother, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, united the interests of the World Trade Center project with a plan to revitalize the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, an aging line that still carried 30 million passengers from New Jersey to New York yearly.

What was unique about the deal that was crafted with the Port Authority was that the Authority was granted the power to raise capital by selling bonds. This publicly backed corporation was a government guarantee that attracted investors to projects that they would have otherwise shunned as too risky.

In 1972, Governor Rockefeller helped out again by leasing the entire South Tower for state government offices. New Yorkers took to calling the Twin Towers “David and Nelson.”

So from the beginning, the history of the Twin Towers and the building that followed their destruction has involved some of the central issues of government, politics and the economy. If the government is going to help the private sector, what community benefit should be extracted? What should the community role in planning be and when should the “technicians” and “experts” be provided a professional cushion from the variety of public voices?

According to Greenspan, “It wasn’t long before the list of things for Ground Zero to house reflected a host of irreconcilable desires: revenge, rebirth, peace, power, empathy, the latest in green design, a park, commercial space, and last but not least, affordable housing.” If you are in favor of public participation, just exactly who counts as the public: People who show up at meetings? Particular interest groups? Those closest to the building site? The families of those who lost their lives? What democratic structures and processes are best fitted to the complexities of rebuilding in the aftermath of 9/11?

My experience at the World Trade Center was mostly spent interacting with workers who were building the tower. One was from Guyana, another was born in Argentina. Vasilka Benn-Williams, whose fellow workers call her “Silky Love” on the job, lives in Brooklyn but was brought up in Trinidad. They were diverse in their backgrounds, thoughtful about their colleagues and union, and proud of their work. This should surprise no one who has bothered to talk to, or take a more rigorous look at, the lives and political beliefs of building trades workers.

Admittedly, my visit to the new World Trade Center was brief, and I only spoke to a handful of building trades workers. But the ones I did speak to displayed a keen understanding of the pressures that buffeted their lives and the union that was attempting to protect them. They understood that the forces that would like that institution to disappear are powerful and are not going away any time soon.

I signed my name on a concrete wall of the 90th floor of the new tower, for those who displayed a courage 12 years ago that the vast majority of us will never be called upon to summon. It will be covered up as soon as the building nears completion. From a southern facing window I could see the Statue of Liberty. A Staten Island ferry sailed slowly past it.

Earlier that morning “Silky Love” had pointed to her favorite sticker on the hard hat she wears, depicting the statue. She provided her own interpretation of liberty, reinforcing for me at least, that the idea cannot be the sole property of the political right. “Freedom for me is the ability to work any way you wish,” she said. “Equal opportunity, equal rights for women on construction sites, for minorities. This sticker stands for that type of freedom.”

(Kelly Candaele is a writer, filmmaker, teacher and has served as a trustee for the Los Angeles Community College District.)

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care