Migrants From Matamoros Find Shelter in McAllen, Texas

Photojournal by Lexie Harrison-Cripps

Published on

In the past week, over 600 people have been transferred from the migrant camp in Matamoros, Northern Mexico, to the Brownsville bus station in Texas. Those who could not afford a hotel or immediate onward travel were offered accommodation at a shelter in Texas.

The Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen is one of those shelters. Formerly a nightclub, it now caters to between 200 and 300 new arrivals each day, said Sister Norma Pimentel, the executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, the organization that manages the shelter.

Three large, crowded and noisy rooms offer a place to rest, and legal advice, showers, clothing and food are available. By the entrance to the shelter, volunteers handed out drugstore products from behind a counter, including baby milk, nappies, face masks and toiletries. A barrage of intrusive loudspeaker announcements constantly impedes any kind of meaningful conversation.

The population was overwhelmingly made up of young mothers with children under 5. Many who would have crossed the border unofficially before “surrendering freely” to the nearest immigration officer, explained Charlene D’Cruz, a lawyer with over 30 years of experience working in migration, one of the leaders of Lawyers for Good Government, and the director of Project Corazon Border Rights Program, Matamoros.

A handful of the guests in the shelter had arrived from the Matamoros migrant camp the night before. They spent the night sleeping on thin, blue, plastic mattresses before continuing their journeys to other parts of the United States. Those interviewed by Capital & Main planned to go to Florida, Iowa, Louisiana and California.

Hundreds of people rest inside the McAllen, Texas, shelter. Only a few had lived in the Matamoros migrant camp. Most crossed the border unofficially and then presented themselves to the nearest immigration officer, who processed and delivered them to the shelter. The population was made up overwhelmingly of young mothers with children under 5 years old.

A family resting on thin blue plastic mats, where they had spent the night. Despite the pandemic, there was no opportunity for social distancing. A representative from McAllen confirmed that the "building must meet building codes before they are allowed occupancy" and then will be "inspected yearly," although in the past they have closed down facilities like these due to overcrowding.

The blue mats were cleared away in the morning to create a space for mothers and young children to relax and play. Windows were papered over with children's pictures showing their nation's flag, landscapes and butterflies.

Dr. Vincent Honrubia hands out vitamins to young children who climbed on the counter of a pharmacy at the back of the shelter. The doctor volunteers for Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, the organization running the shelter. Honrubia has volunteered in the Matamoros migrant camp, where he treated pregnant women. He estimates that he has seen around 300 families.

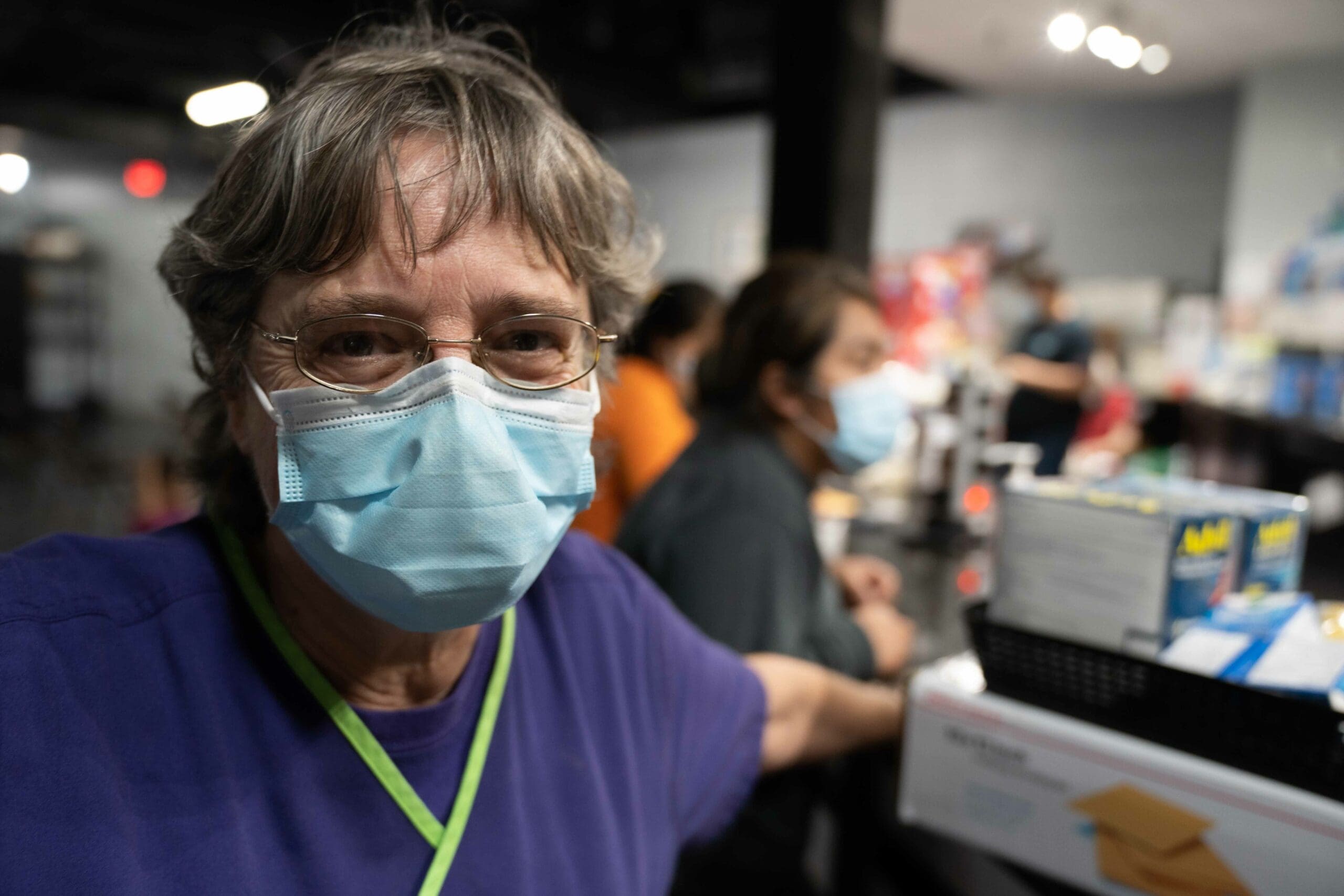

Sister Jacinta Powers, 66, collects medical supplies to take to the COVID testing tents outside of the shelter. She is volunteering for Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley as a nurse. Before working in the shelter, Powers volunteered as a nurse in the Matamoros migrant camp for a year.

Virginia, 89, from Iowa and Fernando, 30, from Honduras behind the counter of the “free store.” Virginia has volunteered for Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley for many years. She admitted that she didn't know anything about her colleague as she doesn't speak Spanish. While making packets of diapers in small plastic bags, she described the guests in the shelter as “wonderful people.” Fernando was helping out behind the counter while his wife stood in the hour long lunch line. They planned to make their way to Los Angeles, where they would stay with his aunt.

Staff served dishes of spaghetti and vegetables to the hundreds of people staying in the shelter. The dining room had around 100 people eating at any one time, spread across 11 long tables. Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley director Sister Norma Pimentel explained that they receive no government funding for the shelter, which is managed entirely from donations.

A long line of people waited patiently for food. Some had been here for over an hour.

A worker in the shelter delivers trays of food to the hungry residents. They sat at long tables inside the dining room, in a building that had once been a nightclub.

A box of pears in the dining room. Guests in the shelter said that they had been fed chicken, fruit, bread and coffee.

Jerson Bonilla, 42, from Honduras, serves bread in the dining room. "It seemed bad that everyone was eating and nobody was helping," Bonilla said.

A few days before, he had been resting in a colorful hammock in the Matamoros migrant camp waiting for the U.N. to register him. At that time, he had no idea that he would shortly be allowed into the U.S.

Jerson Bonilla waits to speak to legal advisers about the next stage of his journey. He planned to go to Louisiana to stay with his brother. Bonilla must first apply for a work permit before his brother can help him find work as a builder. Bonilla described the feeling of crossing the border and being allowed into the U.S. as "inexplicable happiness."

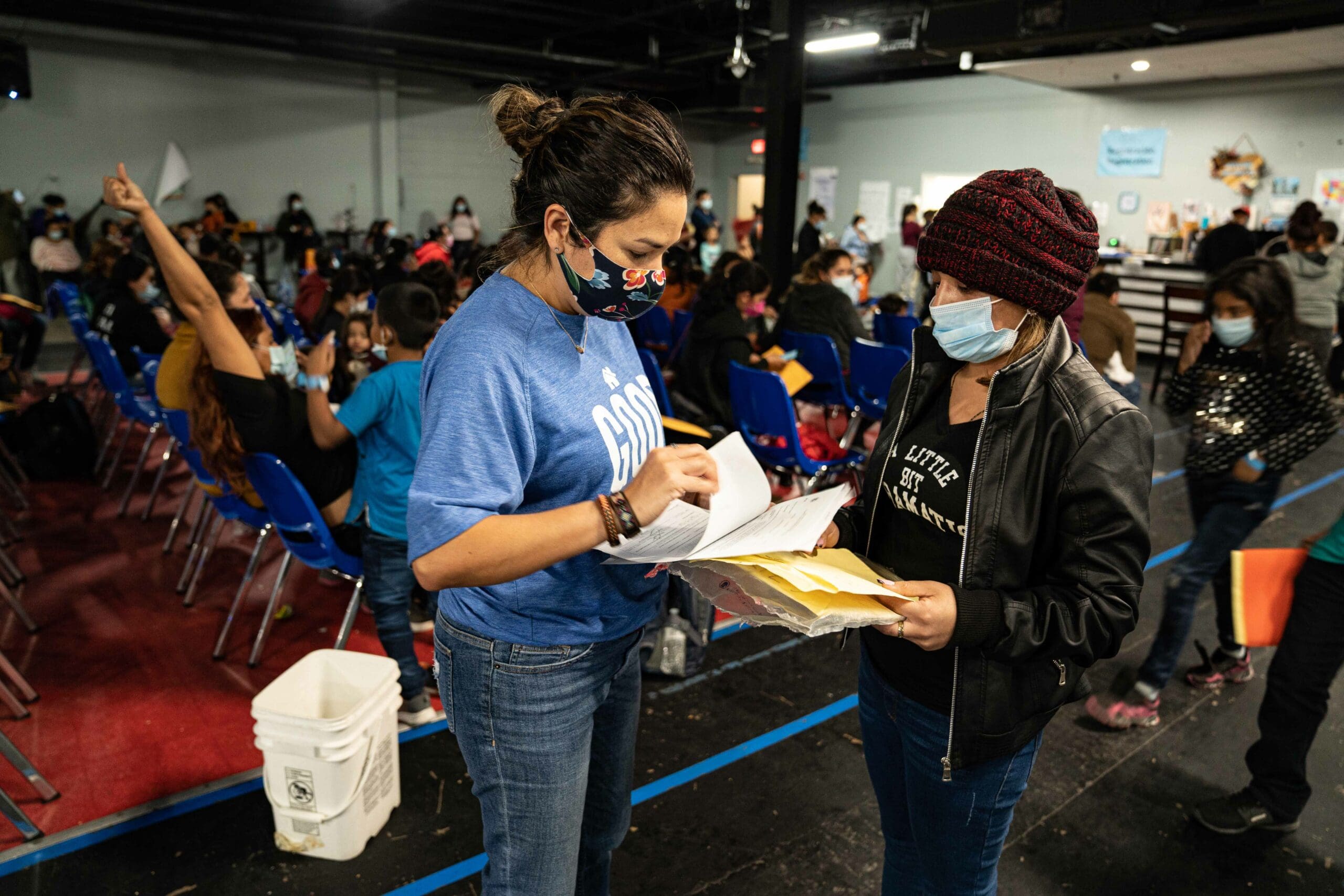

Daniela, 23, from Honduras, talks to a Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley worker about her paperwork. She planned to take a bus that night to Florida where she would be reunited with her 6-year-old son. Daniela cried as she explained that it was safer to send her son, then 5, over the border on his own, with nothing but her brother's name and address in his pocket. With regular kidnappings and assaults, many parents made the same decision in Matamoros. Her son spent three months in the care of the U.S. government before he was delivered to her brother in Florida.

One room in the shelter has beds for sick people and space for mothers to rest with their newborn babies. People form a line in the middle of the room for new clothes. Some arrived with only the clothes on their back.

Workers in the shelter hand out clothes to residents.

In the clothing distribution area, a bright pink sequined princess dress, seen in the background, hung on a rail labeled “maternity.”

All Photographs by Lexie Harrison-Cripps

Copyright Capital & Main 2021