Labor & Economy

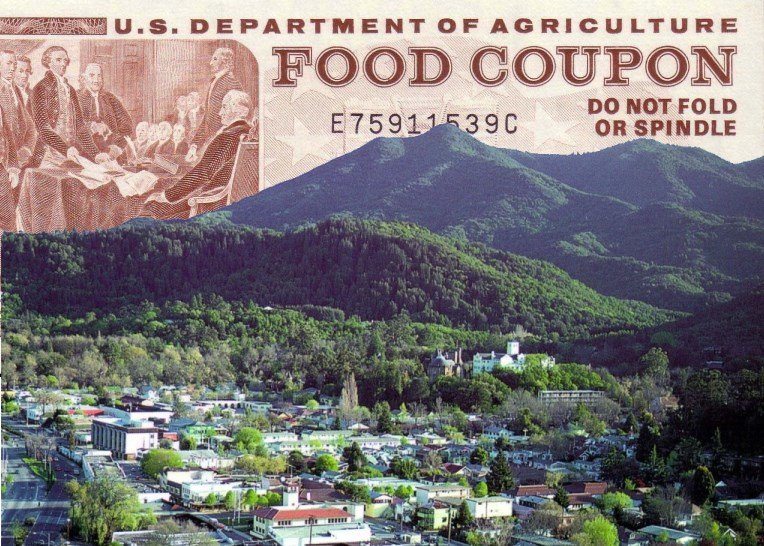

In the Midst of Plenty: Food Stamps in Marin County

There are many student cars parked at and around Sir Francis Drake High School — some of them expensive BMWs, some environmentally correct Priuses. But when Justice Levine attended classes at this Marin County school, she had to walk to Drake, passing rows of expensive San Anselmo homes. That was nearly seven years ago. Then 14, she would wake up in the morning to an empty house and make her own breakfast — her mother had already left for work for the day.

![]()

This is an encore posting from our State of Inequality series

Their rented home — one floor of a modest two-story house — was not well-furnished, most of its fixtures were secondhand and it lacked the semblance of interior decorating. Now 21, Levine describes it as a space she and her mother occupied separately for a long time, following the mother’s divorce.

“There’s a big difference between the houses of people [like us] and those that can afford a lot, because it’s a part of their showmanship — they can show their wealth through their houses,” Levine says. “Then there are people who have to work a lot, whose house is just where they live. It’s more of a shelter than a luxury.”

There are many of the former in Marin County, where the median household income is $90,000, a cool $30,000 more than the California average, and where the poverty rate is 7.7 percent — half the state’s rate. Marin is affluent, but that doesn’t mean that income inequality doesn’t exist here.

Levine moved to the county from New Mexico when she was 10 years old, to live with her mother. In her Santa Fe elementary school, it had been harder to detect the disparity between the wealthiest family and the poorest.

“When I moved to Marin, I realized that there was an entire wealth bracket above me that I had never seen before,” Levine says.

Levine’s mother had been establishing a new life in Marin a year before her daughter arrived. Back in Santa Fe, she had operated a preschool out of their house, but her teaching degree wasn’t recognized in California. She took up several jobs, teaching yoga, art classes and working as an after-school program supervisor. With her multiple jobs, the mother didn’t have a typical 9-to-5 schedule.

Levine and her mother applied for county benefits and were placed within the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), more commonly known as food stamps. The stark difference between her situation and her peers’ was frustrating.

“It felt a little like I was being used as a charity case,” Levine says. “It’s a difficult thing to deal with because you know they’re not trying to insult you by helping you out, but at the same time it’s hard not to get offended when people say certain things or act in a certain way.”

The hardest reactions came from her fellow students. As part of SNAP, Levine was eligible for free lunches at high school. In her sophomore year, she was rejected because the school failed to notify her that she needed to renew her eligibility forms. She tried to explain the situation to a peer, who looked at her incredulously.

“He said, ‘You get free lunches? That’s not fair,’” Levine says. “I told him it was because my mom couldn’t afford to pay for it and he said, ‘Why doesn’t your mom get a job?’”

For the most part, it wasn’t difficult for Levine to blend in with the rest of the class. But certain aspects of everyday life that were minor blips for other students were significant for her — everything from receiving scholarships to attending prom (requiring an $80 ticket to travel to a venue in San Francisco) to getting a copy of the yearbook.

Those who live in Marin affectionately refer to it as “The Bubble.” It’s where one can expect a certain type of person whose income, interests and political affiliation are likely to reflect their neighbor’s. Perhaps for adults, there was more awareness about income inequality, but Levine found that the knowledge barely trickled down to their children.

She says that most people her own age thought poverty meant the homeless people they observed in nearby Oakland and San Francisco. They couldn’t fathom that someone who attended the same school and did the same things they did could be in poverty. They didn’t know what poor looked like, she says.

The differences were subtle, but profound. Levine would receive $30 for a shopping excursion; her friends were handed $300. If she went out with her peers, she didn’t buy lunch or drop money on trivial items. When she started working in her junior year, most of her paychecks went toward outings with friends, to match their behavior.

When she was younger, Levine says, she felt angry that her mother couldn’t provide her with the same lifestyle as that of her peers. She says in hindsight it’s the ignorance of the privileged that bothers her most.

“If you’re poor, you have to look poor and you can’t have the same luxuries that everyone else has,” she says.

Many people wouldn’t understand if someone receiving food stamps owned an iPhone, she says. They would argue that money spent on iPhones should go toward food, shelter and other basic necessities.

“There’s a double standard here because we’re supposed to admire our rich for their affluence and decadence, and then we shame people for trying to have that same lifestyle when they can’t afford it,” Levine says. “It’s very segregating. I’m trying to fit in where everyone has a lot. When I try to have a lot, I’m shamed for it.”

After graduating from Drake in 2011, Levine moved back to New Mexico to pursue art at the Santa Fe University of Art and Design. She hasn’t been back to Marin County in more than six months, but there’s still a small slice that’s followed her to Santa Fe.

“People here [at college] know where Marin is. I’ve been called a spoiled rich girl,” she laughs.

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care